hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

“We have a right to know our history”: Fraudulent records keep Korean adoptees from the truth

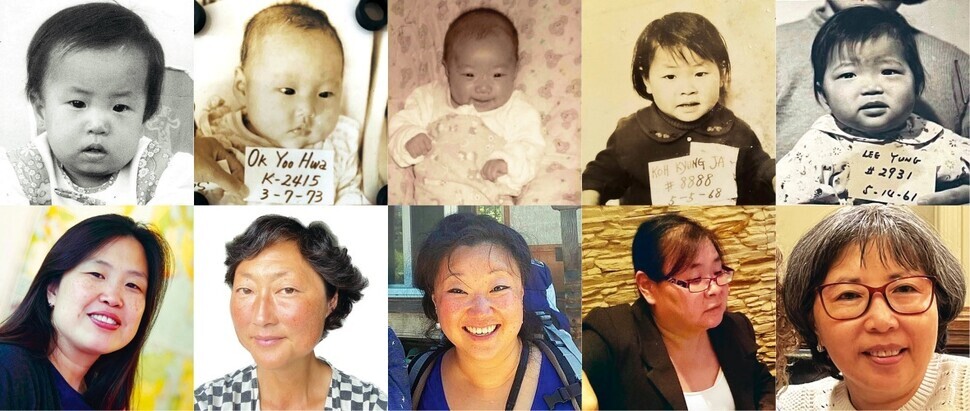

Editor’s Note: To mark the 35th anniversary of the newspaper’s founding, the Hankyoreh is featuring the stories of 20 transnational Korean adoptees in several installments. May 11 was Adoption Day, and this year marks 70 years of international adoption from Korea.

South Korea is also the third country in the world, after Chile and Ireland, to launch a state-level investigation into human rights violations in the adoption process.

The Danish Korean Rights Group (DKRG) is the world’s largest community of Korean adoptees, with more than 650 members from 10 countries, including Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Germany, the Netherlands, and the US.

Since August 2022, the group has submitted 334 adoption cases to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea for investigation, leading to the opening of the investigation into human rights violations in the overseas adoption process in December 2022.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission plans to conduct a local investigation in Copenhagen starting in June. The attention of the estimated 200,000 Koreans who were adopted across the world is on the case.

The Hankyoreh respects the desire of international adoptees to restore truth and justice by looking into their history, which has been tampered with from their birth by instances of infant trafficking and record falsification.

These brief personal histories of 20 adoptees are accompanied by their hopes for the TRC investigation — that the truth is revealed, and they can reconcile with their past.

So many open questions

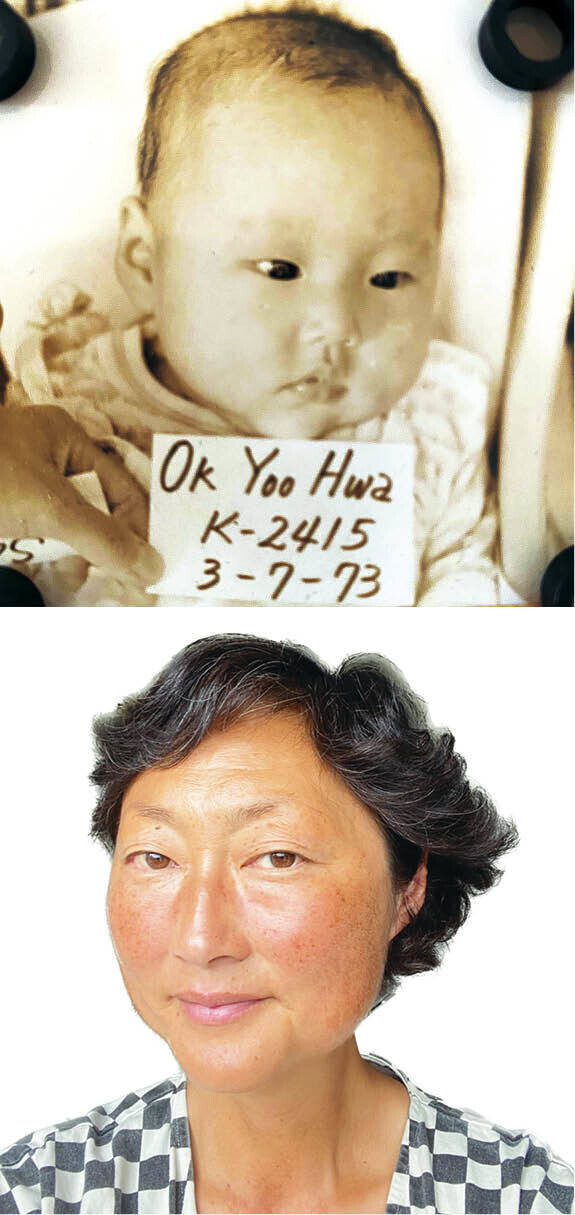

Marianne Ok Nielsen. Adopted at 9 months old (estimate). Currently 50 years old (estimate). Denmark.

Growing up I had the privilege of eating well, living in a home with caring adoptive parents situated in peaceful Denmark. But I’ve never had the privilege to know the name of my birth mum. Who carried me in her womb for nine months? When did she deliver me? Where in Korea did this happen?

Having grown up I have learned that I shouldn’t trust the information in my adoption papers where they say I was found in the streets of Daejeon when I was only six months old. Having grown up I have realized that these questions do matter to me even though I was in denial up until my 30s as I was busy trying very hard to be as white and Danish as I could. Having grown up my mind knows there had to be a reason for my mum to give me up, but my nervous system is wired with the baby’s notion that it must be my own fault that I was abandoned. That there’s something wrong with me. That I’m not worthy of love when even my own mum didn’t want me.

So for me, the big open question of all is: Why?

Why, dear mum, did you leave me? Why couldn’t you keep me? Did you try? Why haven’t you been looking for me?

I am so deeply grateful that the TRC has taken mine and the rest of the cases and the worldwide work the DKRG does is life-changing and so important. Not only for more than 200,000 grown-up adoptees shipped out of Korea but also for their children around the world and their Korean birth families who are all impacted.

The focus and awareness of the mental and emotional consequences of transnational adoption for the children can never be exaggerated. On top of that, all the cover-up and the lying and the reluctance of providing information that is defined as human rights is just appalling and outrageous.

My hope is that the TRC case will result in full access to the true archives of the adoption agencies, making it possible for us as adoptees to search for our biological heritage. I hope that a program will be launched in Korea in order to collect more DNA profiles to increase the possibility of a match. Hopefully, there will be a greater understanding of how immense a robbery transnational adoption is. Our true identity, culture and language have been stolen from us and at the same time we have been told to be happy and grateful for being sent away.

My personal and naive hope is that I might get to know the identity of my birth mum. If miracles happen, she will still be alive. And willing to meet. Even though we no longer share the same language I wish we would still share the same love.

Only learning I was relinquished after meeting my birth family

Stephanie Dong-Hee Kim. Adopted at 4 months old. Currently 43 years old. Netherlands.

In the first 41 years of my life, I thought I had all the information there was to know about my adoption. I thought I knew the truth. I had based my life and, most importantly, my self-worth and my place in this world on this information. Now that I am 43 years old, I have discovered that so much of what I believed has proven to be wrong. The truth turned out to be a lie.

The truth is, that my mom did the unthinkable: She relinquished me for overseas adoption and told my father and my sisters that I had passed away. If I were a boy, I wouldn’t have been adopted. If I were a boy, my younger brother wouldn’t have existed. My sisters and I have been angry with our mom for a long time.

Over the past 15 years since our first reunion, my family has taught me a lot about Korean history and culture and specifically our family’s history.

Nowadays I am convinced my mom was not a bad mom, she was no evil and careless woman. Neither was my father. They were so poor that the adoption agencies — like predators — were praying for these easy-to-catch victims. The adoption propaganda worked so well, my mom thought abandoning me was the only thing she could do.

My parents did not receive support from any children’s welfare organization, nor from the Korean government. My parents were second-generation victims of the Japanese occupation and the Korean War. Both their families were traumatized. My parents were forced into this situation because of immense poverty. Because of a culture where boys were more important than girls and immense pressure from both their families to produce a son. Because of the fact that selling children to Western families made KSS earn money and childcare and protection only cost money. Because of inequality.

The truth can be ugly, confronting, painful and traumatic. Our truth is. But I prefer the truth over a lie anyway. My parents deserve to be freed of the shame and guilt that is put upon them by society. I deserve so as well. All parents and all adoptees deserve a life free of shame. It is our human right that we know our true history, so we can reconcile with the past and take lessons and blessings into the future.

The trauma of adoption has affected every area of my life

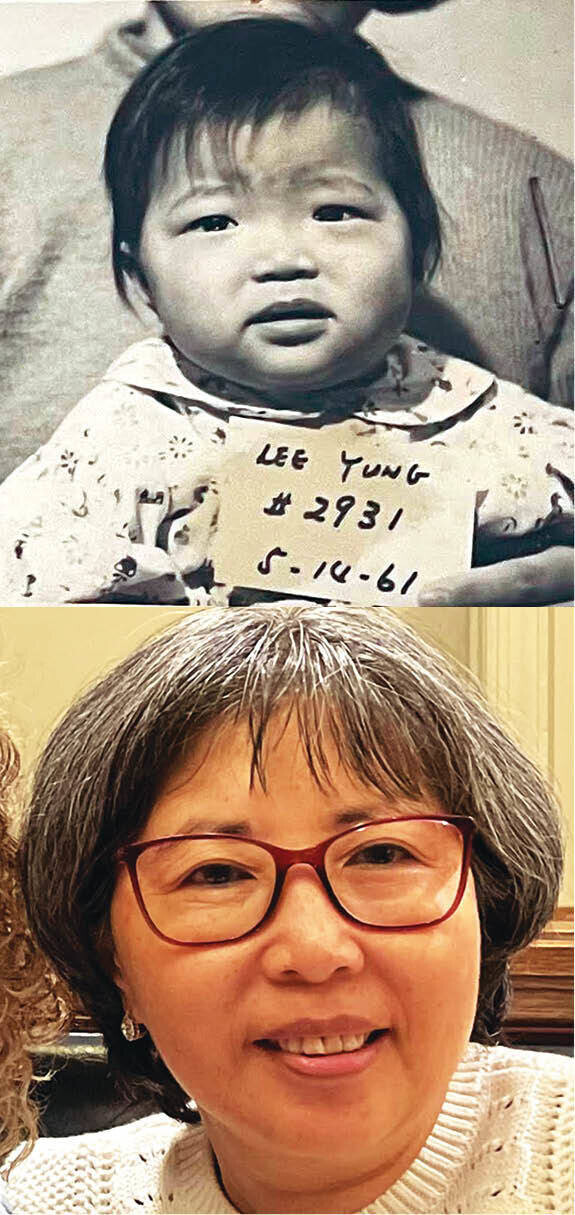

Margaret Conlon. Adopted at 4 months old. Currently 62 years old. USA.

I was intrigued when I first came across information regarding the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) through the Facebook group “Korean American Adoptees” (KAA). The story of my adoption through Holt in 1965 to an American family may be changed greatly according to the TRC outcome. Thinking that I was relinquished instead of being abandoned is turning my self-perception upside down.

Years ago, when I tried to search for my birth mother, apparently, I was fed the same story as many other adoptees: I was told that there was not enough information in my file to conduct a birth search. I am now left wondering if I was told lies again. I would like to personally participate in this far-reaching and life-changing process of making the institutions that were to protect the vulnerable accountable for their actions.

I feel I suffered needlessly because of the lies fed to my American family and myself. I feel cheated out of a normal Korean life and forced to grow up as an American with all the angst of being different. I had no access to racial mirroring; I can still remember the first time I saw Asian people. It occurred at a Chinese restaurant, no less. The trauma of adoption has affected every area of my life: self-identity, relationships, career, and motherhood. I suffered from racist comments and gestures throughout my childhood, including being spat upon. I still face racism as an adult, but not as severe.

Today’s standards for childcare consider corporal punishment as child abuse, even though I did not believe I was being physically abused. Completing a questionnaire about violations of human rights during the adoption process prior to writing this essay made me face the abuses I suffered at the hands of my adoptive parents. Looking back on my upbringing, I see that I was also emotionally abused. Love was only given when I was behaving like a good little Christian girl. I did not have the emotional or physical support that I needed as I went through my first divorce. My parents told me that they loved me just the same as their biological kids, but I saw that it was not true. My adoptive sister to this day treats her girlfriends much kinder than she has treated me.

I have been searching my entire life for self-identity. I do not know who I really am without relationships. My identity has been formed and reformed throughout my life according to the whims of my relationships. I do not have a strong sense of self-identity to stand alone. My name has changed as my relationships have changed. I have many aliases, starting with my Korean name “Lee Yung.” I struggle with forming relationships within my family and in the world at large. I am quick to end a relationship that is beyond my ability to maintain. I am not close to any family members; in fact, I am currently estranged from my adoptive father and his biological daughter. I was closer to my son until he got married and had his own child.

I had looked forward to having my own children, as a newlywed, because I imagined that they would create a nuclear family for me and mark my place in this world. As it turns out I have one child, and he himself has one child, making my place in this world tenuous at best.

In every adoption case I’ve seen over the last year, misdirected or falsified information

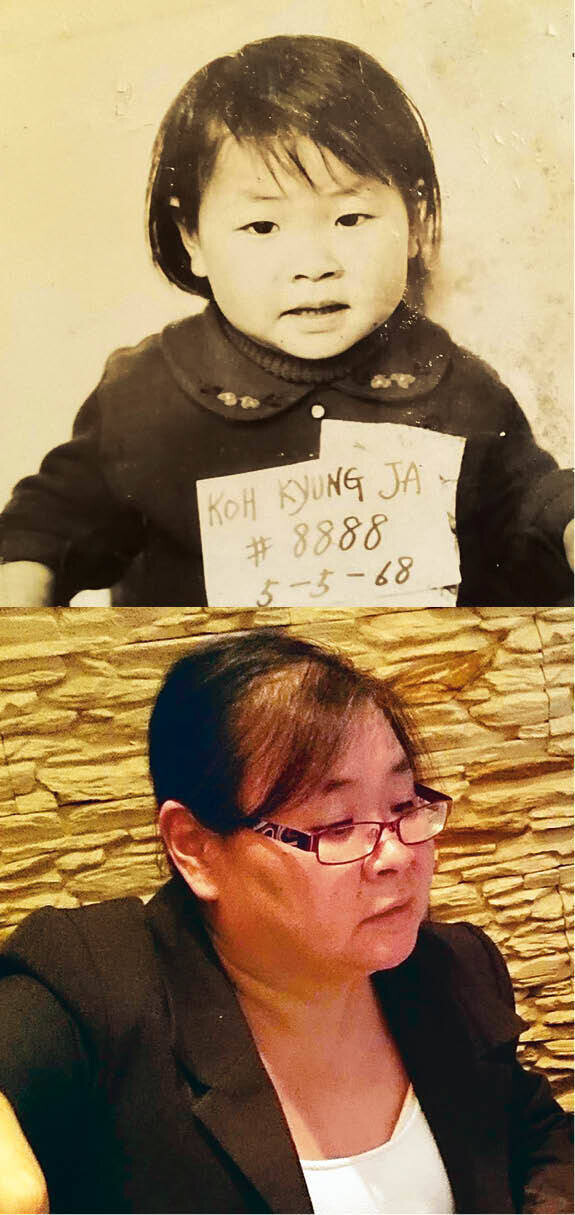

Nia Kyung Ja Lee Koh Toftager. Adopted at 3 or 4 years old. Currently 52 (estimate). Denmark

My name is a mix of my given name in Denmark and the name I presumably was given in Korea. This combination of names has been my name since I was 19 years old.

My history can be kind of weird and messy for those of you unfamiliar with my story. I’m presumably born in the Year of the Monkey, more specifically 1968. I’m presumably born with cerebral palsy, but that’s uncertain too.

And the first thing I know (not a memory, I only remember very little about my childhood) is what I have read from my adoption papers: that I was adopted to Denmark on Dec. 13, 1971. But now that too, is hardly an undisputed fact, as the family who adopted me has always told me that I arrived on Sept.22, 1972, and became a Danish citizen that year.

Well this is the beginning of my journey in Danish society, and as I grew up, I tried my very best to adapt, but early on I knew I couldn’t and that I didn’t want to either.

Today, memories of my childhood and youth only remain with me as a fog, seemingly events from a time far and distant away. I chose to work in a Chinese restaurant, because it gave me the opportunity to be around fellow Asians and for the first time someone to mirror myself in.

Although almost 9,000 Korean children were adopted to Denmark and the country is small (half the size of South Korea), many of us only connected much later in life.

Since 1970 there have been smaller groups for and with Korean adoptees. The first attempt at such a group was made by our adoptive parents. Is hard to pinpoint what the exact purpose of this group was, because on one hand our adoptive parents wanted to provide us with info and knowledge about our birthplace, but on the other hand, if we didn’t adapt to Danish society, culture and norms, we were considered and treated as pariahs. My best guess is that Korea and Korean culture was simply used to make otherwise ordinary social gatherings a bit more exotic. Later, adoptees themselves as they (we) were coming of age established an organization focusing on finding back to their roots.

As time has passed, I’m still curious as to why so many Korean children were adopted away. A practice not only dominant in the 1970s, when Korea was considered a poor country, but also in the 1980s and even today, when we otherwise learn that Korea is at the highest in technology and many other things. Indeed, Korea is well-known and popular. Even my daughter loves K-pop, K-beauty and K-dramas, because all these Korean cultural productions are popular in the Western world today.

Many have tried through the years to pursue family search and connect with their Korean heritage, and I am no different. Last year, in 2022, when the world opened up after the COVID-19 pandemic, I stumbled upon one of my Facebook friends who tried to gather people to investigate their adoption and cases. The more I heard and learned about this initiative the more it felt that this was my opportunity to know how and why I landed in Denmark all those years ago.

I’m all too aware of the disability, but I decided long ago that I will not let this be a hindrance for anything. So I began to read more about adoptions from Korea and I reached out to fellow adoptees to hear if I could help our collective cause.

Indeed, 2022 turned out to be quite an exciting year. I went to Korea and made friends for life, and I left my dear mother country with a promise to myself that I could do my best in helping others find their truth and a path for the future. So, I have for the past year or so read and deciphered one set of adoption documents after the other. I have hosted “timeline” sessions, during which we help each other to map out the process of our adoption process, step by step, one date at a time.

I’m certain that it is collective efforts such as these that have brought us this far with the Truth and Reconciliation Commission — and I’m happy to play just a small part in this.

And when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in December 2022 accepted the first batch of cases, my hope rose, not to find ancestors, but to find the truth because it seems in every adoption case I have seen over the past year, there has been misdirected information and falsified information. Going through my own adoption documents again, I thought, “Hmmm, it can’t just be a mistake or that someone forgot.” It sadly seems that many of these documents have been made as a cover-up to hide that I was/we were merchandise, like a doll or a puppy. I’m still struggling to digest these findings. Perhaps we all need time to digest and reconcile with this chapter of adoption history.

So yes, I joined the DKRG, which in the past months seemed to have developed into a movement for the right of adopted children, that every one of us adoptees has the right to know our history and own our history too, like any human being. I hope I will get more pieces of my history. Both for my own piece of mind, but also for my kids to know.

We want to give our children a family history, something we never had as adoptees

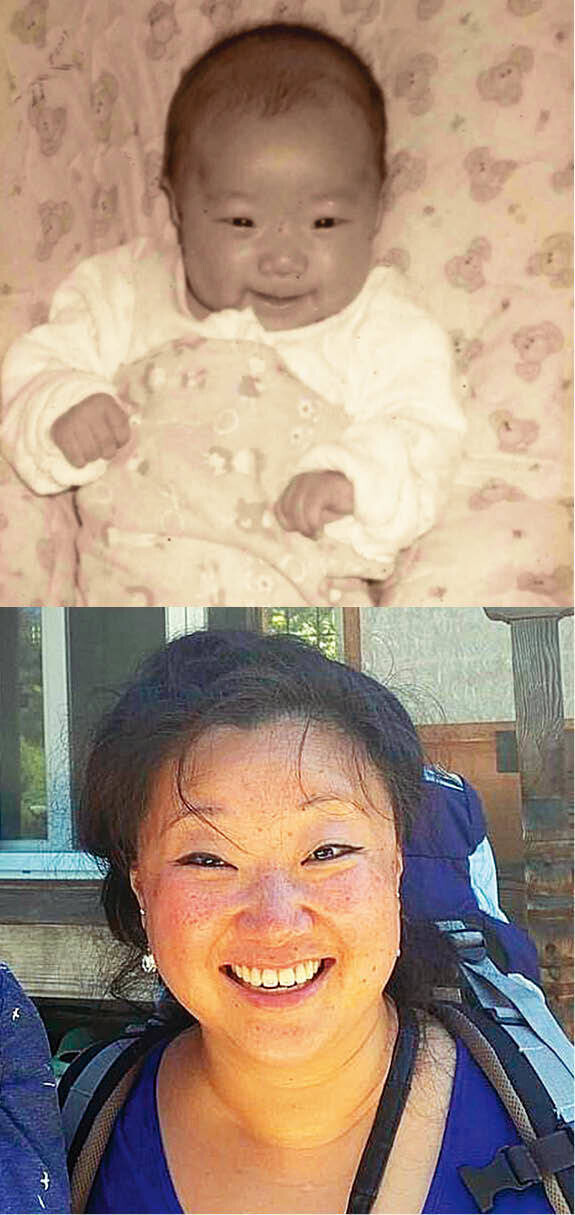

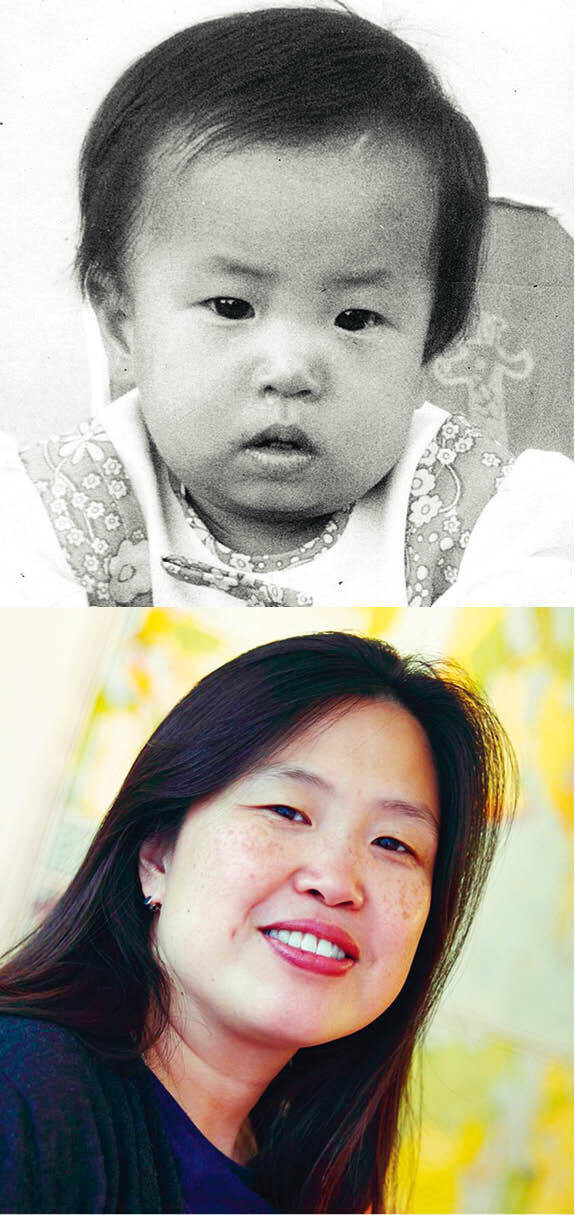

Erika Blikman. Adopted at 4.5 months old. Currently 47 years old. Netherlands.

Not knowing your real name, birthdate, family, reason for adoption, language, and culture is traumatic, but despite the loss, most of us still function relatively well; we have good jobs and have started our own families.

My Korean name is Suh Joon Hee. This name may not be accurate, and was probably given by a social worker from Korea Social Services. The same goes for my family origin that was on the family registration file, it’s Ree Chun.

According to the police report, I was found on Sept. 1, 1975, at around 1:15 am in front of Boys Home located at San7, in the Amnam neighborhood of Seo District, Busan. The baby’s admission request has been filed via the Seobu Police Station. She was about 2 years old when found by a driver named Wang Hwang-hyun, who was 24 years old. The reporter was driving a Jeep (license plate: Busan1Ga5556). He was driving with two journalists when he discovered the baby at Boys Home and reported finding her to the Seobu Police Station.

After that I stayed at the NamKwang Temporary Shelter before going to KSS.

On Jan. 24, 1976, I arrived in the Netherlands. A farmer and a housewife raised me in the countryside. I grew up with two brothers, the youngest was also adopted from Korea. I did well, studied at three different schools/institutions/universities and graduated from all of them. I’m working for a theater company in Rotterdam and raising twin daughters, now 8 years old.

I’ve been to Korea on several occasions. Most of the time for work or holiday. Last time was in summer 2022. After a visit to KSS on Aug. 17, I wrote in my diary:

“I should have walked here together with my husband and our 2 daughters. Instead, I went alone with our girls. No husband next to me.”

We want them to have a family history, something that I and my husband, who was also adopted from Korea didn’t have. Not just any family history but our family history. It was something we felt was important because we missed having one and when my husband found out that he was terminally ill he started to write about his life for the girls. Then it was always possible for them to remember him.

Hana and Bo missed having their dad with them on this trip. They miss having a dad. And I can’t fill the empty space. I want to, but I have to accept that that space will always be empty. Because we will always miss him. No adoption document will ever help, but at least it would bring our children closer to their father. Even though he is no longer with us anymore, his adoption documents are not ours to keep. The small family history we have is not ours. It belongs to the adoption agency. With a very heavy heart, I left the place.

Owning our history and coming to terms with it is so important because we never had a choice in our adoption. Others made that decision, and it impacted our lives to this day. I truly hope that the TRC case will open doors for us, that it will shift the narrative about international adoption in Korean society, and that we adoptees and our children get better post-adoption services from the Korean government.

“What has been done cannot be made undone, we can only move forward and try to be a better person than we were.”

By Koh Kyoung-tae, senior staff writer; Kwak Jin-san, staff reporter

Joint planning and execution by Han Boon-young, co-founder of the DKRG

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0514/2317156736305813.jpg) [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line![[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0514/7917156741888668.jpg) [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

- [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

- [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- 2Major personnel shuffle reassigns prosecutors leading investigations into Korea’s first lady

- 3[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 4US has always pulled troops from Korea unilaterally — is Yoon prepared for it to happen again?

- 5Korean opposition decries Line affair as price of Yoon’s ‘degrading’ diplomacy toward Japan

- 6Korea cedes No. 1 spot in overall shipbuilding competitiveness to China

- 7[Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- 8[Photo] Korean students protest US complicity in Israel’s war outside US Embassy

- 9Naver’s union calls for action from government over possible Japanese buyout of Line

- 10For prestigious university admission, S. Korean students and parents in a war for information