hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

New testimony sheds light on untold massacre of villagers by Koreans during Vietnam War

Editor’s note:Fifty-nine years ago, on Sept. 11, 1964, Korea sent 140 soldiers belonging to the medical corps to Vietnam as part of the war effort. Over the nine years that followed, South Korea would end up sending a total of 346,393 troops to fight in Vietnam in its Blue Dragon, Fierce Tiger, and White Horse divisions.

In 1999, Hankyoreh 21 broke the story that South Korean troops had massacred civilians in Vietnam with in-depth reporting. More than 20 years later, in February of this year, a South Korean court ruled that the country bears a legal liability to those victimized by these massacres. However, the South Korean government still insists that no such slaughter occurred.

In the intervening decades since the war, 60 memorials to those lost and “monuments of hatred” condemning the atrocities and their perpetrators have been erected across Vietnam in areas where Korean soldiers were deployed during the war.

The Hankyoreh revisited the sites of Vietnamese civilian massacres and rekindled the memories of 60 years ago to tell the story, for the first time, of the massacres in Bình Thanh and on the island of Lý Sơn.

Thình thình, thình thình.

They say that strange noises can be heard on the mountain. Thình thình — the thump of a person’s weight hitting the ground, the smack of a heavy stone falling to the earth. Thình thình — a thumping heartbeat in the forest. That’s how Mount Tình Thình got its name.

It took 20 minutes of navigating along the winding cement road to reach the mountaintop. At Mount Tình Thình’s peak, 168 meters above sea level, the whole village of Bình Thanh is visible.

Located at the top of the mountain is Tình Thình Temple, which dates back to 1920. Our visit happened to fall on the day of a dharma meeting, and the temple was bustling with people.

Bình Thanh is only 100 kilometers south of Đà Nẵng, a popular tourist destination for Koreans. But no Koreans could be seen in the village.

The temple’s abbot, 49-year-old Thích Đồng Lộc, welcomed the Hankyoreh reporters as we pulled into the temple. He appeared to have much to say to these Korean visitors.

“Did you see the big well in front of the temple?” he asked. “The South Korean soldiers used to draw water from it to wash and drink.”

The well at the entrance to the summit of Mount Tình Thình was more than 2 meters wide. Peering down through the wire mesh, it was so deep as to appear bottomless entirely.

“It was small and dilapidated, but the South Korean soldiers cemented and renovated it. If any of them are still alive, they would definitely remember the well,” Thích Đồng Lộc told us.

Thích Huyền Đạt, a monk who passed away in 1994, had passed down many stories about the South Koreans to the younger monk during his lifetime.

This is the first time that Bình Thanh is being named in the history of Korea’s involvement in the Vietnam War that began in 1964. Bình Thanh is not mentioned in the official “War History of ROK Forces to Vietnam” published by Korea’s Department of Defense in 1979.

Bình Hòa, a town to the north, has become well known as a site where Korean forces massacred more than 430 civilians, with a stele of hatred erected there naming Korean troops for their atrocities. Yet Bình Thanh has been left out of the historical record. But now we share testimony from this village.

“Many of the South Korean soldiers were Buddhists, and they sometimes came to worship and make rice offerings,” the abbot shared. It seems that South Korean soldiers left many fond memories behind at the temple.

“In the old days, there was only one mountain path to the top of Mount Tình Thình. It was so narrow that only one person could go up at a time, so the South Korean troops didn’t use that path to come up here.” If the troops mentioned here were indeed South Korean troops, they would likely have belonged to the Blue Dragon Division.

They used helicopters to get in and out of the base on the mountain. When they withdrew, they reportedly burned down the base facilities to the ground and buried all the documents and other items they had been using.

“Just before evacuating, a soldier came to the monk Thích Huyền Đạt and gave him a small piece of gold, telling him to renovate the temple after the war.”

It would have been touching if the story ended there. Thích Đồng Lộc wasn’t the only one who remembered the South Korean soldiers. Several Bình Thanh residents told us that some of them were preparing a “monument of hatred” dedicated to South Korean troops.

“We picked peppers,” said 67-year-old Tống Thị Kim Loan, whom we met at Bình Thanh commune in the Bình Sơn district of the province of Quảng Ngãi on Aug. 5.

57 years ago, as a 10-year-old girl, Tống Thị Kim Loan said she picked peppers in the fields with her grandfather, Tống Mai.

The sun stung her skin as she labored in the pepper fields. The Vietnamese peppers were small and spicy, and the villagers had heard that South Korean soldiers couldn’t get enough of them.

The young girl and her grandfather packed the peppers in small bags and took them to the Korean soldiers at the Go Cot base.

At first, it was US forces that were stationed in Bình Thanh, but one day in August or September of 1966, the Americans packed up and left. Soon after, a new crop of soldiers arrived — ones who were shorter than the Americans and had Asian features. South Korean soldiers.

Having landed in Vietnam in October 1965, the South Korean Army’s Blue Dragon Division had traveled through Tuy Hòa, Phú Yên Province, to Quảng Ngãi Province in the north. Village residents became anxious at the arrival of these strange soldiers.

In August 2023, residents of Bình Thanh spoke to the Hankyoreh for the first time about the massacre.

When Tống Thị Kim Loan’s grandfather, Tống Mai, arrived at a South Korean military post, he had Vietnamese peppers and a letter in his hand.

He was accompanied by Cao Phó and Mai Cắt, who lived in his same village. The three of them represented the village and faced the South Koreans for the first time.

All three were born in the 1890s and were over 70 years old at the time. Their letter to the South Koreans was written in Chinese characters. Having learned to read and write Chinese characters from a young age, they assumed that the Koreans would be able to read it as well.

The South Korean soldiers based in Bình Thanh did not have interpreters. The letter contained a heartfelt plea from the village elders: “The villagers are all innocent civilians. Please do not harm them.”

A young Tống Thị Kim Loan was holding her grandfather’s hand when he presented the Korean soldiers with the letter and his gift of peppers.

A month after Tống Thị Kim Loan and her grandfather offered the chilis to the soldiers, the South Korean soldiers paid a visit to Tống Thị Kim Loan’s neighborhood. Instead of gifts, they brought guns.

“They set off smoke bombs and then opened fire with submachine guns,” Tống Thị Kim Loan shared.

The South Korean soldiers visited her house early in the morning, before breakfast, at around 6 or 7 am, she said.

They forced the family outside. She stepped outside with her mother, 30-year-old Mai Thị Én, and younger brothers, 7-year-old Tống Phuong and 6-year-old Tống Hoang. Six members of Von Ke’s family, who lived in the same neighborhood, were also dragged out into the street, making for 10 people in total.

At first, the soldiers handed out canned food, most likely C-rations.

Some of them started to set up a submachine gun under a big tree. After some time had passed, there was a huge bang, as if something had exploded. Then, there was smoke everywhere. It was impossible to see anything. The soldiers had set off a smoke bomb.

The thunder of the gun rattling off its bullets shook the ground, and the sound was ear-splitting.

Tống Thị Kim Loan grabbed her mother and hid behind her. People fell to the ground as they screamed, and Tống Thị Kim Loan happened to fall underneath everyone else.

The gunfire stopped. So did the groans of agony.

Tống Thị Kim Loan’s mother and two younger brothers weren’t moving. Everyone in Von Ke’s family was as still as stone. Everyone, apart from Tống Thị Kim Loan, was dead, their blood still pooling on the ground.

Tống Thị Kim Loan seized her wits and got up. She wondered if the soldiers had set off the smoke bombs because they were afraid to see what they were doing, mowing down people with their guns.

The soldiers left the village to return to their base without checking the bodies, which was a stroke of luck in Tống Thị Kim Loan’s favor. She suffered only a small burn on her stomach.

She can still remember the chilling sensation of the bullet grazing her belly.

Tống Thị Kim Loan’s mother and siblings were buried on Sept. 12, 1966, of the lunar calendar. In the Gregorian calendar, the anniversary of their deaths falls on Oct. 25.

According to the Ministry of National Defense’s “War History of ROK Forces to Vietnam,” the Blue Dragon Division left Tuy Hòa on Aug. 18, 1966, and traveled to Chu Lai and Quảng Ngãi provinces.

Since the division was large, it took them a month to move, arriving at their destination on Sept. 15.

There is no detailed record of this period in the “War History of ROK Forces to Vietnam,” with records absent until Nov. 8.

All that is recorded is that “while conducting unit maintenance, the division conducted a golden operation to protect the civilian’s harvest on Sept. 24, and after that, with the cooperation of the US and South Vietnamese forces, the division conducted a non-belligerent operation to defeat enemies in the area to stabilize the tactical area of responsibility and relocate some of the company tactical bases.”

There are no mentions of how they defeated the enemies in the area.

Tống Thị Kim Loan’s father, who had fled from the scene, returned at night to collect the bodies with the village elders. A banana tree was planted at the grave of the girl’s mother.

Her mother had been in full term. Planting a banana tree to celebrate a pregnancy was a village tradition. When it was time to give birth, villagers celebrated the birth of a new life by eating bananas from the tree.

However, her mother would never be able to commemorate anything any longer.

“All the village elders who visited the soldiers with the chilis died,” said Le Van Hien, 76.

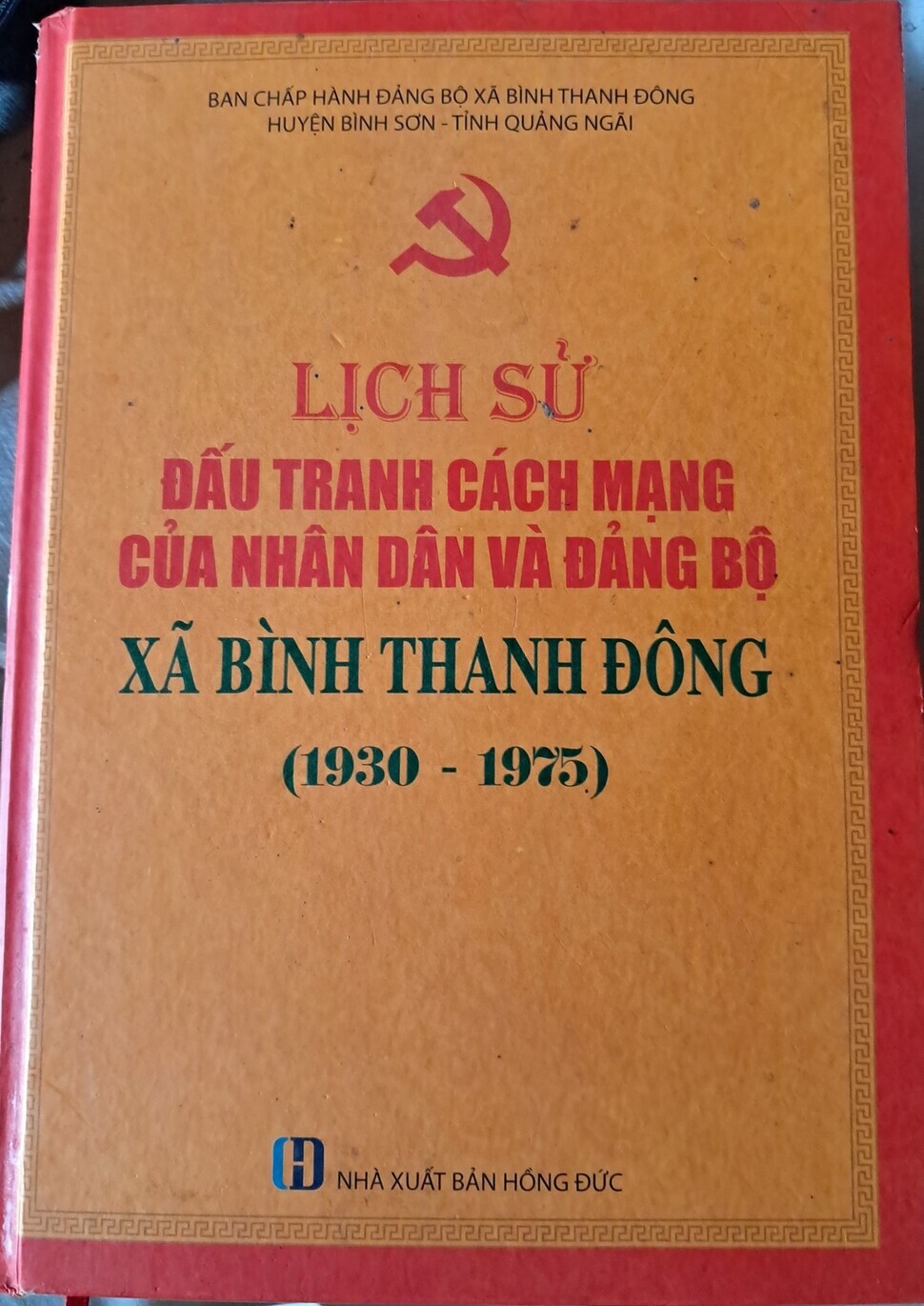

Presenting a list he wrote on the computer, Le Van Hien pointed at the three names at the top of the list: Tống Mai, Cao Phó and Mai Cắt. These were the names of the village elders who had visited the South Korean soldiers with the bag of chili peppers and a letter written in Chinese characters.

Tống Mai, the first name on the list, was Tống Thị Kim Loan’s grandfather.

“The South Korean soldiers took the chili peppers but killed the elders later on. They killed Tống Mai first while searching the village and later killed Cao Phó and Mai Cắt at the same time,” said Le Van Hien.

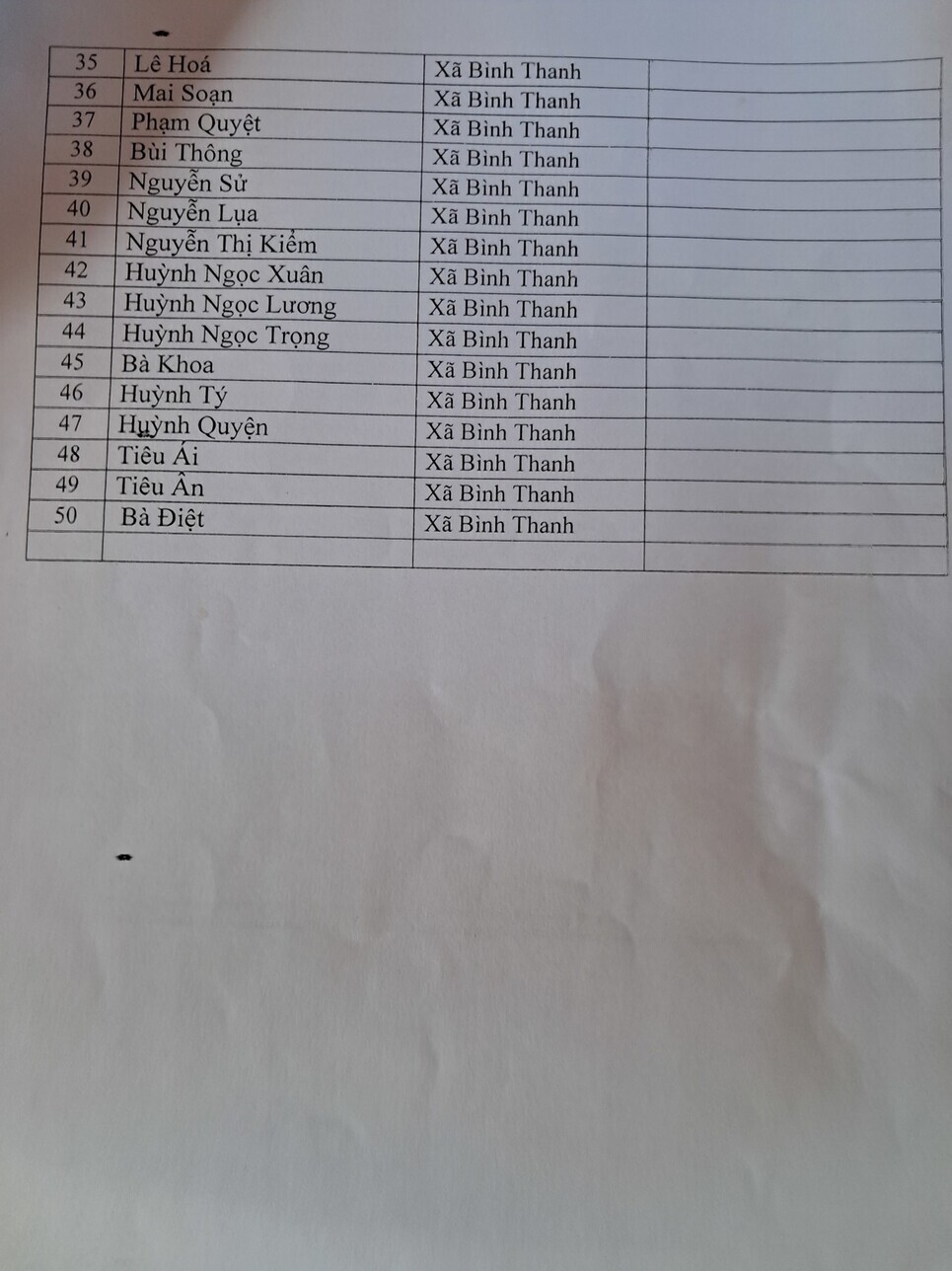

The list he showed was of Bình Thanh residents who had been slaughtered by South Korean soldiers from 1966 to 1967.

An armed guerilla fighter as a 20-year-old in 1966, Le Van Hien lived on the mountain. His father, Le Soan, who lived in the village, and his second eldest brother, Le Tao, were murdered by South Korean soldiers on Sept. 26, 1966, and Oct. 17 of the same year, respectively.

Le Van Hien and other local residents stated that there were four South Korean bases and guard posts located in Bình Thanh: in Bình Hiệp, Giông Tranh; Go Cot Chánh Hội; Đồng Phước, Đồng Hoà; and at the top of Mount Thình Thình. If a unit the size of a company was located at the top of the mountain, located at the center of Bình Thanh, a small platoon was located in Go Cot, where Tống Thị Kim Loan went. South Korean soldiers left this area beginning on Dec. 21, 1967.

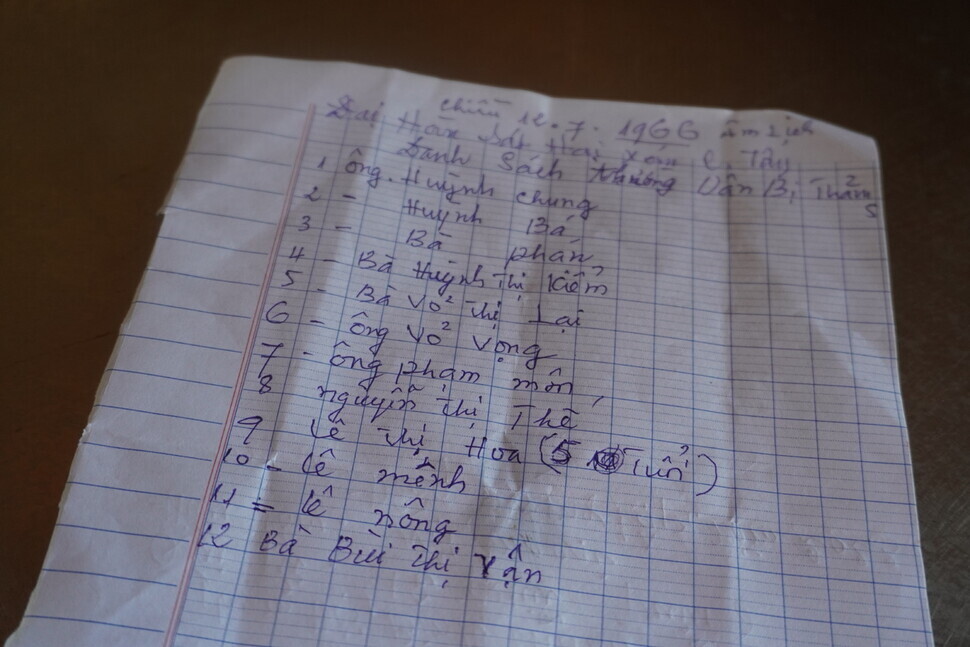

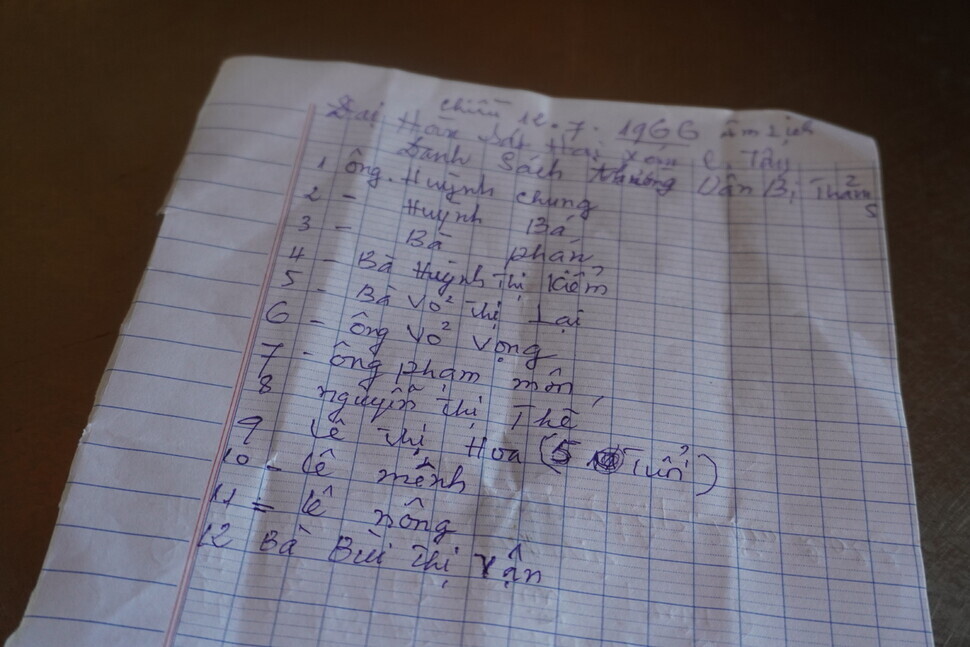

Le Van Hien has been recording the history of how the people of Bình Thanh fought against outside forces. His records from 1930 to 1975 have already been published into a book, which contains stories of people who died at the hands of South Korean soldiers. Saying he began compiling a list of resident witnesses only recently, Le Van Hien showed another piece of paper. This one had been handwritten and contained a list of 12 additional witnesses, which would bring the death toll of the civilian massacre perpetrated by South Korean soldiers to 62. Once finished with his investigation, Le Van Hien said he would propose a memorial for victims to be built.

Following the end of the Vietnam War in April 1975, memorial monuments were erected in villages where residents were lost at the hands of South Korean soldiers. Monuments of “hate” were built in places such as Bình Hòa and Phú Yên. In some regions, monuments were erected 50 years after the war. In Quang Hau, Điện Bàn, Quảng Nam Province, a monument was finally erected in 2019. According to the Korea-Vietnam Peace Foundation, 60 such memorial monuments have been built across Vietnam. But no such monument stands in Bình Thanh yet.

“I will propose the erection of a monument of hate rather than a memorial monument,” said Le Van Hien, explaining that this is because all the victims were helpless elders, women and children. Referencing the Vietnamese government’s slogan of overcoming the past and moving toward the future, Le Van Hien wordlessly shook his head.

“Still, I can’t help but hate. Incidents like this should be abhorred forever,” he said.

By Koh Kyoung-tae, staff reporter; Kwak Jin-san, staff reporter; interpretation by Nguyễn Ngọc Tuyền, professor of Korean at the University of Đà Nẵng

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing? [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0705/2917201664129137.jpg) [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?![[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0703/8717199957128458.jpg) [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor- [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy

- [Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- [Editorial] Silence won’t save Yoon

- [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

Most viewed articles

- 110 days of torture: Korean mental patient’s restraints only removed after death

- 2What will a super-weak yen mean for the Korean economy?

- 3[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

- 4Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 5Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty

- 6Koreans are getting taller, but half of Korean men are now considered obese

- 7Democrats ride wave of 1M signature petition for Yoon to be impeached

- 8In the blink of an eye, an unthinkable crash turned a night out into a nightmare

- 9Democrats seek to impeach 4 prosecutors, including those tied to probes into Lee Jae-myung

- 10Beleaguered economy could stymie Japan’s efforts to buoy the yen