hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

Common denominator of drastic social decline in East Asia: Low birth rates

“The three East Asian countries of Korea, China and Japan may have different historical trajectories, but the drastic social decline they’re undergoing is exactly the same,” said Shin Kwang-young, professor emeritus at Chung-Ang University.

The question posed by Shin is what Korea, China and Japan ought to be concerned with right now.

“The three countries were quite different in the past, through the end of the 20th century, and they frequently engaged in fierce conflict. But the grim future they’re all facing is exactly the same,” he opined.

Shin delivered a keynote address titled “Different Pasts, Same Futures” on the first day of an international academic conference marking the 10th anniversary of the establishment of the DAAD-Center for German and European Studies at Chung-Ang University. The conference was held at the university, in Seoul’s Dongjak District, from Nov. 10-12.

At the present, Korea, China and Japan are the leading economic powers in East Asia.

China has the world’s second-biggest economy in terms of GDP, as well as the second-biggest military in terms of its defense budget.

Japan has the world’s third-biggest economy in terms of GDP and has the most net external assets of any country.

While Korea was formerly subjugated first to China and later to Japan, it has surmounted that past to become one of the world’s 10 biggest economies.

All three countries have forged powerful economies through surprisingly rapid economic growth, but today, in Shin’s view, they all exhibit social degradation that endangers their sustainability.

The first signal of the social degradation that Shin describes is the low birth rate. The structural changes that would push the birth rate below the rate needed to maintain the population (the replacement fertility rate, 2.1 births per woman) began in Japan in the late 1950s, in Korea in the early 1980s and in China in the early 1990s. While the fertility crisis began at different times for each of the three countries, they are now all facing the same demographic cliff.

Japan’s total population has been decreasing since 2005; the decrease this year is projected to be a stunning 800,000 people. As of 2022, Japan’s total fertility rate was 1.26.

Korea’s population has been shrinking in absolute terms since 2019. In 2022, it posted the world’s lowest total fertility rate of 0.78.

China’s absolute population began to shrink last year, and in 2022, China posted a total fertility rate of 1.09, its lowest in history.

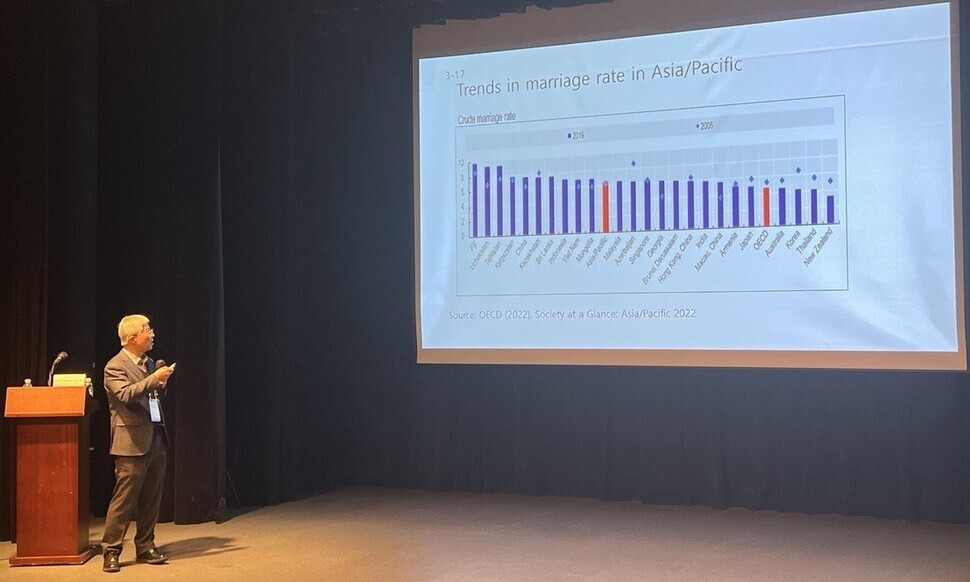

In Korea and Japan, low fertility is the result of fewer people getting married. Those who do get married do so at a later age, and more and more people are determined to never marry at all.

Shin explains that China’s experience is subtly different from that of Korea and Japan: while the number of marriages is increasing, a large percentage of married people are simply not having children. The implication is that significantly different trends can lead to the same low birth rate.

A low birth rate is accompanied by a high population aging rate, or the percentage of the total population aged 65 years or above. The population aging rate in Japan (as of 2022) was 29.1%, making Japan what is known as a “super-aged society,” defined as a country where 20% or more of the population is over 65.

Korea is also on track to become a super-aged society, with the 65+ demographic making up 17.5% of the population in 2022. Korea is expected to see that rate hit 20% for the first time in 2025.

Last year, the 65-and-above segment of China’s population rose above 200 million, giving the country a population aging rate of 14.2%. That moved China from an aging society (with an aging rate of at least 7%) to an aged society (with an aged rate of at least 14%).

Korea is in particular trouble among the three countries given the speed of its aging. Korea already has more than 9 million people aged 65 and above, and it’s projected to take just seven years to move from an aged society to a super-aged society. That’s faster not only than Western countries such as the UK (50 years), France (39 years) and the US (15 years), but also than Japan (10 years).

This demographic lurch isn’t the only social issue being faced by Korea, China and Japan. They’re also enduring severe inequality and witnessing the emergence of a new stratum of poverty.

In 2021, China had a Gini coefficient (a measure of income distribution) of 0.466. Japan was at 0.334 and Korea at 0.331 in the same year. Considering that income is distributed more equally as the Gini coefficient approaches 0, China’s high score enables us to infer the severe inequality in that society.

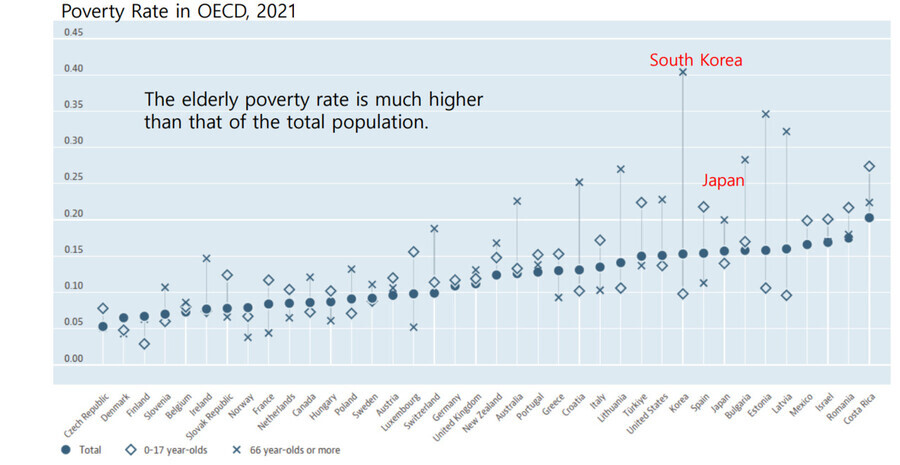

There has been widespread coverage of poverty among the elderly, which is also witnessed in all three countries. In 2021, the elderly poverty rate in Korea was above 40%, while China had a rate of 19% (as of 2020) and Japan of 20%.

The elderly poverty rate in most developed countries in the West is below 15% (except for the US, where it’s 23.1%). And in the wealthy countries of Europe, the elderly poverty rate is generally below 10% (9.1% in Germany and 4.4% in France, for example).

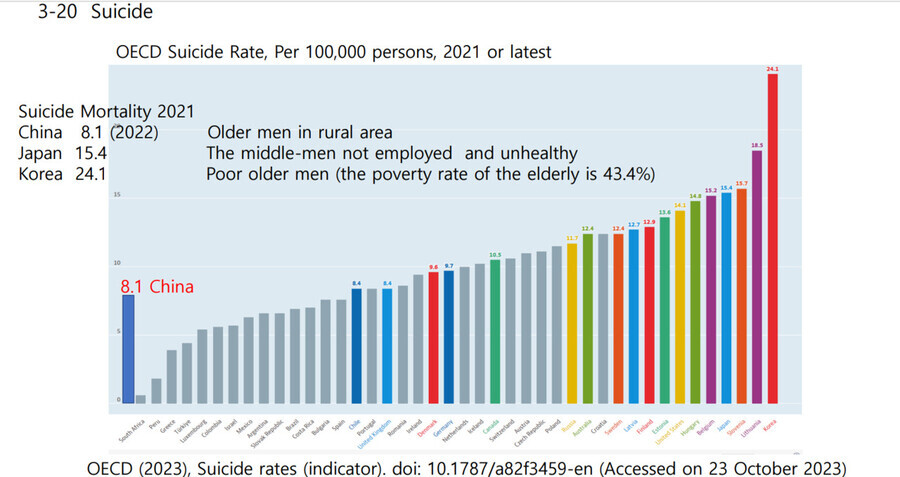

These social issues loom even larger when we consider their correlation with suicide rates. In 2021, Korea had the highest suicide rate among any OECD member state, at 24.1 people per 100,000 population. Japan’s suicide rate in the same year was 15.4, while China’s rate has been on the rise, reaching 8.1 in 2022.

“In Korea, the elderly poor make up a large number of suicides. In Japan, suicides are common among sick and unemployed people of middle age. And in China, there are many suicides among elderly people working in rural areas. That shows us who the most vulnerable people are in each country,” Shin remarked.

Western countries have mitigated or resolved such social issues through taxation and welfare policies. But Korea, China and Japan are failing to reduce the severity of these issues, Shin remarked, because of poor tax systems and social policy in all three countries and because of low spending on welfare in Korea and China in particular.

“In the end, what the three countries of East Asia have in common is being solely interested in economic growth, which has left them incapable of properly addressing the various social issues that arise as a result,” Shin said.

He predicted that if current trends continue, “The three countries of East Asia will all be unable to avoid serious social degradation within one generation.”

“The only way to avoid this dark future is to build a society in which ordinary people are able to live in peace,” Shin reiterated.

By Lee Chang-gon, senior staff writer

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1Behind-the-times gender change regulations leave trans Koreans in the lurch

- 2Yoon’s revival of civil affairs senior secretary criticized as shield against judicial scrutiny

- 3Family that exposed military cover-up of loved one’s death reflect on Marine’s death

- 4South Korean ambassador attends Putin’s inauguration as US and others boycott

- 5Marines who survived flood that killed colleague urge president to OK special counsel probe

- 6A breath of fresh air: Innovative architecture in the time of COVID-19

- 7‘Weddingflation’ breaks the bank for Korean couples-to-be

- 8Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023

- 9Hybe-Ador dispute shines light on pervasive issues behind K-pop’s tidy facade

- 10[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?