hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] A pilgrimage honoring a lover of Korean plants and trees

“Until Aug. 14, 2014, I knew nothing about Father Émile Joseph Taquet, his burial site, the king cherry tree, or the tangerine. But then someone told me about the king cherry. It was Kim Gyu, who lives right in front of the archdiocesan curia in the Namsan neighborhood of Daegu. In passing, Kim told me a story he’d heard from his grandfather about Taquet’s connection with the king cherry and about the convent and cathedral where Taquet’s funeral mass was held. That story marked the beginning of my journey.”

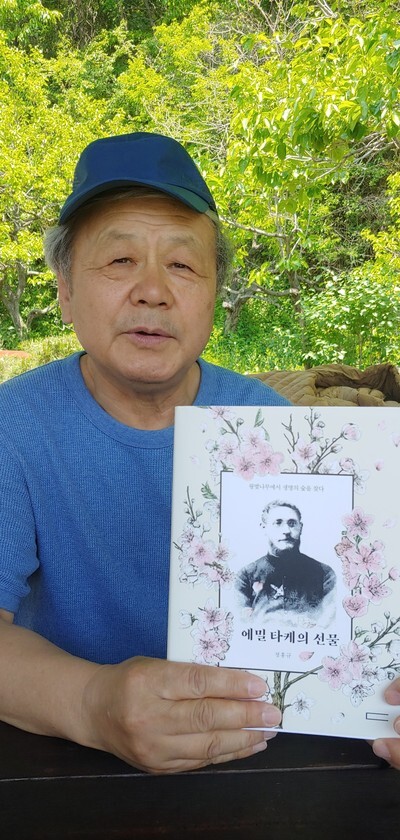

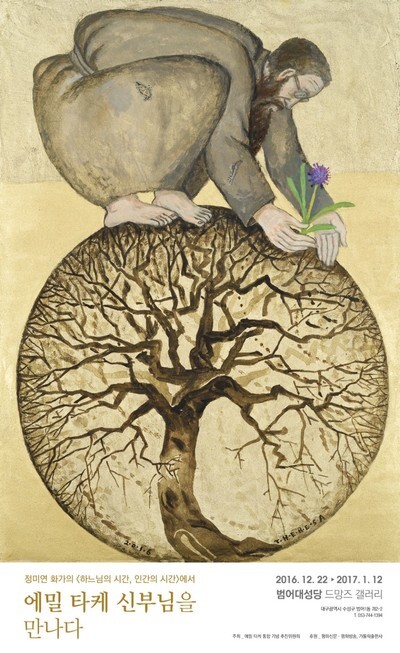

Five years later, that journey culminated in the book “The Gift of Father Émile Taquet: Finding the Forest of Life in the King Cherry Tree,” which was recently published by Da Vinci. On May 19, the Émile Taquet Plant Research Institute opened at Cheongdo Arboretum, located in Deoksan Village, Maejeon Township, Cheongdo County, North Gyeongsang Province. On May 11, the Hankyoreh sat down with the author of the book and the director of the research institute — Father Jeong Hong-gyu, 65, christened as Augustine — at Holy Mother Pine Forest Village, a church in Cheongdo, on May 11.

“Early in the morning on Aug. 15, the very day after I heard the story from Kim, I visited Taquet’s grave at the clergy cemetery in the Namsan neighborhood and held my first mass for him. That day, I started exploring the area around the archdiocesan curia and found the king cherry trees there. I guess people never see what’s under their own nose, but I was dumbfounded to think that decades had gone by without anyone knowing.”

That day marked the beginning of a “120-year pilgrimage” for Jeong, who had recently been appointed as an associate professor at the Catholic University of Daegu. On that pilgrimage, he hoped to trace not only Taquet’s life but also the plant samples he’d collected and the trees he’d planted.

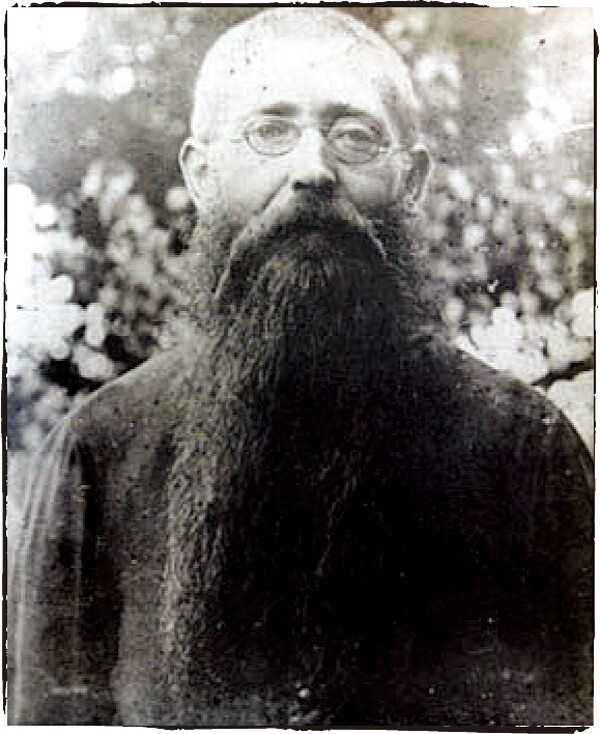

In 1898, at the age of 24, Taquet was sent to Korea (then called Joseon) by the Paris Foreign Missions Society. He remained in Korea as a missionary for 55 years until his death in Daegu in 1952. After stints at the main churches in Busan, Jinju, and Masan; churches in Hanon and Hongno on Jeju Island; the Sanjeong neighborhood church in Mokpo, and Noan church in Naju, Taquet was assigned to serve as a professor at St. Justin Seminary in Daegu in 1922, a position where he remained for the rest of his life.

Taquet sent more than 10,000 plant samples to botanist in Europe, US, and Japan

Jeong’s own journey was focused on Jeju, where Taquet spent the first 13 years of his missionary work, collecting plant samples of the king cherry tree and the Korean fir. While spending a month at the House of Remission, a church in Seogwipo (the location of Hongno church, where Taquet had his first assignment in 1902) Jeong retraced Taquet’s steps past Hanon church and a gingko tree to Seogwipo church. Taquet sent more than 10,000 plant samples from Jeju to botanists in Europe, the US, and Japan, and even today his plants and records are still found at universities and botanical gardens around the world. His name is attached to the scientific name of some 125 species of plants that he was the first to discover, such as Dryopteris taquetii Christ and Rosa taqueti H.Lév.

“I found myself getting more curious about why Taquet focused on collecting plants when he’d come to Korea to do missionary work. He’d studied under Father Urbain Pori, a botanist who’d previously worked in Japan. In 1901, shortly before Taquet arrived on Jeju, hundreds of Catholic believers there had been slaughtered in an uprising. That meant the conditions for missionary work there were quite poor, and the Paris Foreign Missions Society also provided Taquet with financial support for the plant samples he sent, which provided his motivation. But at any rate, isn’t it interesting to think that it was through the interaction of these two priests that the king cherry tree was sent to Japan, and the tangerine from Kumamoto Prefecture was sent to Jeju Island in return?”

Jeong found one thing in common about the sites he visited on his year-long journey: wherever Taquet had served — Namsan neighborhood in Daegu, Wanwol neighborhood in Masan, Yangcheon neighborhood in Naju, and so on — there were ancient specimens of the king cherry trees. “I couldn’t find any records of when, where, or how Taquet had actually planted the king cherry trees, so I asked botanists for some help.”

Jeju’s cherry tree is native to the island and distinct from the Japanese sakura

In June 2015, the Daegu Archdiocese carried out an on-site investigation of two king cherry trees in front of Aniksa Temple and Daegeongwan, in the archdiocesan curia, at Jeong’s request. A survey by Kim Chan-su, director of the Jeju Warm Temperate and Subtropical Forest Research Institute, along with other experts, found that the two trees were 88 and 61 years old, confirming that they’d been planted after Taquet became a professor at St. Justin Seminary in 1922.

At a conference called the Comprehensive Ecology of Émile Taquet’s King Cherry Trees, which was hosted by Catholic University of Daegu that next April, researchers reported that the 88-year-old king cherry tree at the Daegu archdiocesan curia was genetically identical to a cherry tree designated Natural Monument No. 159, located in the tree’s natural habitat on Mt. Halla, Jeju Island. The tree in Daegu, in other words, was descended from the very king cherry tree that Taquet had first collected on Mt. Halla and reported to the academic world, proving that the king cherry was indigenous to Korea, and distinct from Japan’s “sakura” cherry tree. The area around the archdiocesan curia also contains other similarly aged trees of Jeju origin, including the Chinese hackberry, glossy privet, and Siebold’s crabapple.

“The more I learned about Taquet, the more strongly I felt it was my mission to raise awareness of how much he’d contributed to Korean history, both as a Catholic missionary and as a botanist.”

The reason that Jeong was able to seize upon something he’d heard in passing and unearth the story of Taquet, which had been buried in history, was because of his own unique background as a priest. Born in Gyeongju in 1954 to a family of Buddhists, Jeong joined the Catholic church at the age of 11 and graduated from Gwangju Catholic University, receiving his holy orders in 1981. Jeong began his pastoral work in the rural areas around Daegu and took part in the Catholic Church’s outreach program to farmers.

Realizing the importance of communities and the environment

“A phenol leak in the Nakdong River in 1991, when I was serving at a church in the Wolbae neighborhood of Daegu’s Dalseo District, was what caused me to fully appreciate the importance of the environment and ecology. I set up an environmental group called Blue Peace, which ran a campaign to make hand soap out of used cooking oil, and started a campaign to encourage urbanites to buy food directly from farmers by holding a ‘domestic wheat party’ in Duryu Park.”

Jeong has long been an advocate of social participation, setting up a number of alternative schools, including Sanjayeon School (in Yeongcheon, North Gyeongsang Province), to provide an education centered on “peace and life.” But it was Jeong’s encounter with Taquet that caused him to reflect upon the pastoral activities to which he has dedicated his entire life and to set out on a new course.

“While I was staying at Hongno church in Jeju for a month in the spring of 2018, I was inspired by Taquet to put this book together. That helped me realize the importance of the inspiration to move beyond the facts and get to the truth.”

Jeong holds that “no one can save the world on their own” and that “the world could be saved if plants became god to man.” Little did he expect that he would meet friends and benefactors who could help him put his convictions into practice. Jeong was able to set up a greenhouse containing plants from Jeju and the Émile Taquet Plant Research Institute inside Cheongdo Arboretum with the help of Son Sang-myeong, CEO of Sina Development, and Kang Sang-yun, CEO of Ajabang, a cafe that doubles as a garden and gallery.

“Moving forward, I want to put together a ‘theology of plants’ focused on Taquet’s ecological spirituality, and his pilgrimage through beauty.” Jeong also said he hopes the world of botany and the press will help him move forward on that journey.

By Kim Kyung-ae, staff reporter

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’ [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/5217153290112576.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’

[Correspondent’s column] The real reason the US is worried about Chinese ‘overcapacity’![[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0510/7717153284590168.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change

[Editorial] Yoon’s gesture at communication only highlights his reluctance to change- [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

Most viewed articles

- 1Korea likely to shave off 1 trillion won from Indonesia’s KF-21 contribution price tag

- 2Nuclear South Korea? The hidden implication of hints at US troop withdrawal

- 3[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- 4With Naver’s inside director at Line gone, buyout negotiations appear to be well underway

- 5In Yoon’s Korea, a government ‘of, by and for prosecutors,’ says civic group

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7‘Free Palestine!’: Anti-war protest wave comes to Korean campuses

- 8How many more children like Hind Rajab must die by Israel’s hand?

- 9Overseeing ‘super-large’ rocket drill, Kim Jong-un calls for bolstered war deterrence

- 10[Photo] ‘End the genocide in Gaza’: Students in Korea join global anti-war protest wave