hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

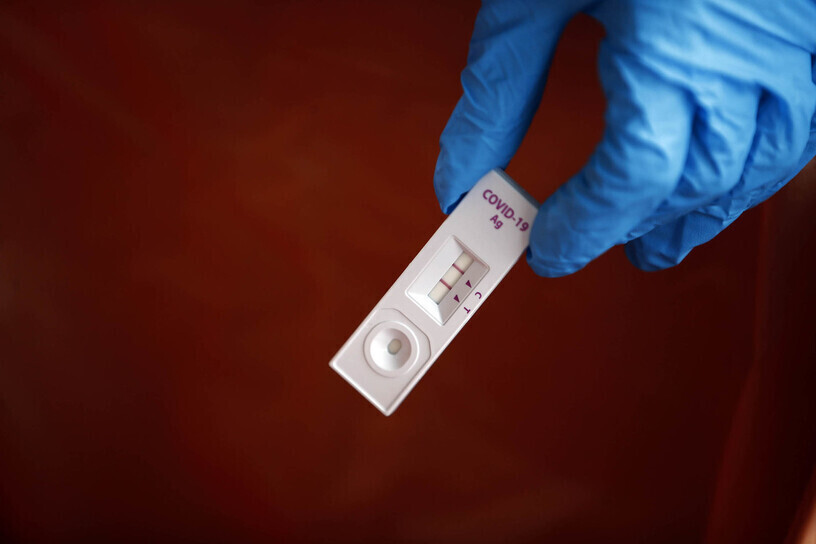

S. Korea mulls shortening isolation for COVID-19 patients, but some experts are wary

South Korean disease control authorities announced that they are considering adjusting the home treatment period for confirmed COVID-19 patients.

As part of the transition toward a system of ordinary medical treatment, they suggested that the designated isolation period may be reduced from its current seven days.

In a briefing Monday by the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Park Hyang, director of the general disease control team for the Central Disaster Management Headquarters (CDMH), said authorities were “currently considering [adjustments to] the isolation period for those subject to home treatment.”

“Discussions are currently underway at the Korea Disease Control and Prevention Agency and elsewhere,” she added.

Under the current guidelines, COVID-19 patients must isolate for a period of seven days from the sample collection date regardless of vaccination status, with a home treatment period of seven days.

While in isolation, patients are prohibited from leaving their homes. Legal measures are prescribed in cases where patients leave their isolation site after diagnosis.

Some other countries have been loosening their policies for mandatory isolation.

In February, the UK lifted the legal requirement for home isolation, replacing it with a recommendation to isolate for five days. In December 2021, the US changed its policies to reduce the home isolation period to five days and require the wearing of masks during outside activities over the five following days.

When asked about the change in the home isolation period, Park explained, “There have been some difficulties so far in terms of general in-person treatment and movement issues for [patients] under ‘focused management’ vs. those under ‘general management.’”

“It appears there is going to be some examination [of reducing the isolation period] in consideration of factors such as in-person medical treatment so that we can transition fully to a regular treatment system,” she added.

In a Central Disaster and Safety Countermeasures Headquarters (CDSCH) briefing last Friday, Son Young-rae, director of the social strategy team for the CDMH, said authorities were considering whether to lift key disease prevention rules apart from indoor mask-wearing in the next two weeks.

“The seven-day home isolation [requirement] is one of the most basic management approaches in our disease control system, so that will need to be discussed separately,” he said at the time.

With the virus’s current surge having yet to stabilize, experts voiced concerns that the shorter home treatment periods could be a risk factor for disease control efforts. In the case of the virus’s Omicron variant, disease control authorities said that patients may continue to shed infectious virus for up to eight days after symptoms appear.

In a CDSCH briefing on March 17, Lee Sang-won, director of the epidemiological research and analysis team at the Central Disease Control Headquarters (CDCH), said, “An investigation of the transmission potential of 558 samples collected within 14 days of Omicron symptoms appearing found that the period during which infectious virus was shed continued for as long as eight days after the symptoms emerged.”

Jang Young-ook, an associate research fellow at the Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, said, “There are quite a few people who retain transmissibility not just for seven days, but for anywhere from 10 days to two weeks.”

“It looks as though they are weighing whether to adjust the system even if it means accepting the transmission risk that such people pose,” he added.

Jang went on to say, “I think it’s too early for a transition when we don’t yet know how the surge is going to play out.”

“Because of the lack of institutional support [in contrast with countries like the UK], with the social attitude that you should continue going to school or work even if you’re sick, the government still needs to institute a mandatory isolation period and provide institutional support,” he advised.

Eom Joong-sik, a professor of infectious disease at Gachon University Gil Medical Center, said, “The disease control authorities set [the isolation period] at seven days based on various research findings, but I’ve yet to see any evidence for setting it shorter than that, so I see it as potentially dangerous.”

“I think it would be better to decide once we’re in a situation where there’s a definite trend of decrease, such as the [daily] confirmed caseload falling below 100,000 with a decline in the number of infected people from high-risk groups,” he suggested.

Chun Byung-chul, a professor of preventive medicine at Korea University said, “Rather than saying ‘we should do this because it’s what other countries are doing,’ we need a basis for it, such as conducting a count for South Korea and finding out whether there isn’t anyone transmitting [the virus] after five years.”

“We can’t base the decision on nothing,” he stressed.

Some analysts also advised weighing looser isolation requirements in the long term.

Jang Young-ook said, “The UK and the countries of North Europe don’t have mandatory isolation for confirmed cases, as they think it’s enough to have treatment for people with symptoms.”

“It’s an approach where people get to choose for themselves whether to undergo treatment based on their symptoms, and I think it’s the right kind of approach for us to adopt in the long term,” he added.

Paik Soon-young, an emeritus professor of microbiology at the Catholic University of Korea, said, “We had the same [concerns] when [the isolation period] was shortened from 14 days to seven.”

“The virus doesn’t go away just because you have a seven-day isolation period, but we may have to find areas where we can compromise in light of the societal costs, as we’re seeing now with healthcare institutions that allow staff to report to work after three days based on their business continuity plan,” he suggested.

By Jang Hyeon-eun, staff reporter; Kwon Ji-dam, staff reporter; Park June-yong, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

Most viewed articles

- 1Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 2Trump asks why US would defend Korea, hints at hiking Seoul’s defense cost burden

- 3[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 4[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- 51 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 6At heart of West’s handwringing over Chinese ‘overcapacity,’ a battle to lead key future industries

- 7Fruitless Yoon-Lee summit inflames partisan tensions in Korea

- 8[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 9South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 10Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors