hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

S. Korean Democrats’ long road to reforming prosecution service: Victory or blunder?

What all began with the prosecution service is now coming to an end with the prosecution service. When the five years of the Moon Jae-in administration are written about in history books, front and center in the table of contents will be the words: “War with prosecutors.”

President Moon Jae-in’s first appointment after being inaugurated on May 10, 2017, was Cho Kuk as Moon’s senior secretary to the president for civil affairs. Moon had promised in his inauguration speech to reform the country’s most powerful institutions. By appointing Cho, a reform-focused jurist who had no history of being a prosecutor, Moon made clear his determination to make prosecutorial reform the primary agenda of his administration.

However, no one ever expected an unconventional personnel reshuffle for the sake of reform to completely shake up not just the government but the entire country in the coming years.

Swordsmen brought in to clean up corruptionOne of the final agenda items for Moon before leaving the Blue House at 6 pm sharp on May 9 has been signing into law legislation aimed at curbing the power of the prosecution service. Under the new reforms, prosecutors’ investigative powers will be reduced to only two major types of crime (corruption and economic crimes) instead of the original six.

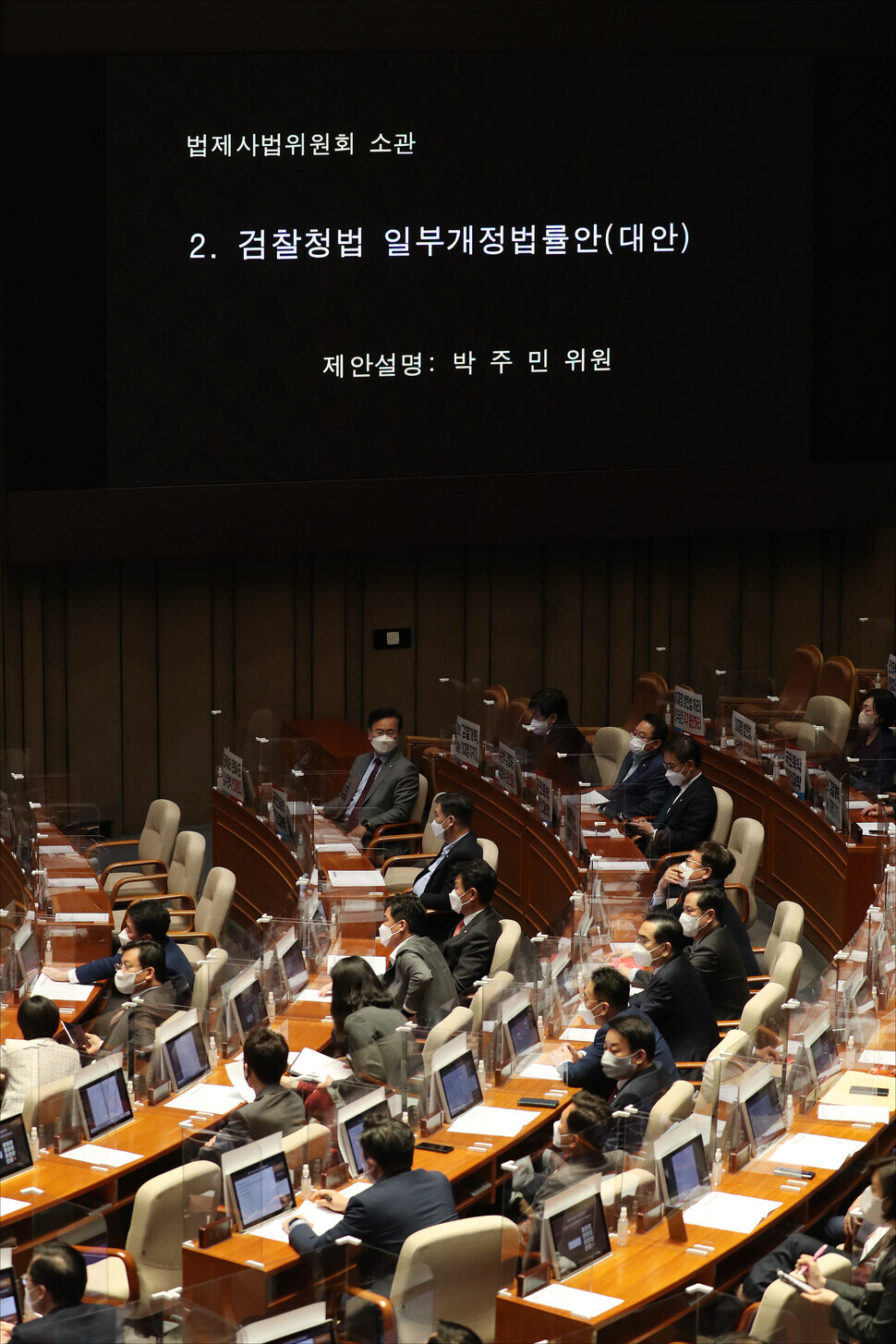

The ruling Democratic Party was able to present amendments, aimed at curtailing the investigative powers of the prosecution, to the Criminal Procedure Act and the Prosecutors’ Office Act at a plenary session of the National Assembly on April 27. The goal was to implement the reforms the administration had been calling for before President-elect Yoon Suk-yeol took office.

Even the opposition People Power Party's filibuster was rendered ineffective by the ruling party's decision to split the session into two. The two bills were passed in plenary sessions on April 30 and May 3, all according to schedule.

Since the 1954 enactment of the Criminal Procedure Act, which granted prosecutors powers of indictment and investigation, no administration in Korea’s history has dared touch the powerful authority of the prosecution service. Although it now looks like changes to prosecutors’ authority are on the way, it is difficult to say whether the entire reform process can be called an achievement, or whether it represents a blunder on the part of Democrats.

There are three conditions that must be fulfilled in order for the reforms to be evaluated as a success: justification, content, and process. So far, it seems difficult to grant the push for prosecutorial reform a high score in any of the three areas. Above all, the political justification for reform has faded during the five years of the Moon Jae-in administration.

Reforming powerful institutions, including the prosecution service, has been a long-standing task for the progressive and pro-reform camps in Korea. According to the results of an opinion poll commissioned by the Hankyoreh to Hankook Research in the early days of the Moon Jae-in administration, 31% of respondents chose prosecutorial reform as “the most urgent reform task for the current administration.”

The poll of 1,000 Koreans aged 19 and older nationwide took place via phone interviews from May 12 to May 13, 2017. It had a response rate of 20.3%, a confidence level of 95% and a margin of error of plus or minus 3.1 percentage points.

Despite deep-rooted distrust in politics and the media, the demand for prosecutorial reform was even higher than that for political reform (21.3%), chaebol reform (12.7%), and reform of the media (11.8%).

It was a time when prosecutors’ conduct of “protecting their own” drew attention during an investigation into Woo Byung-woo, a former senior presidential secretary for civil affairs under Park Geun-hye, which drew public outrage. The time was thus ripe for reform.

The Moon Jae-in administration decided to take action to “clean up” the corruption that had been rife after 10 years of conservative governments in South Korea.

In general, whenever there were calls for prosecutorial reform, the prosecution service would adopt a strategy of launching an investigation as if to justify their reason for existing. This was no different under the Moon administration.

President Moon Jae-in appointed Yoon Suk-yeol as chief of the Seoul Central District Prosecutors' Office nine days after his inauguration, and nominated him for the role of prosecutor general in June of 2019. Yoon soon became a household name, taking on a semi-celebrity status among the public, as evidenced by requests for autographs and handshakes from citizens.

However, the ruling party’s calls to reform the prosecution service became much more urgent later in the year as a result of the clash with Cho Kuk.

One civil society official put it this way: “Prosecution reform was not carried out from a macroscopic perspective, but was used [to cast] political judgment at the time. As the relationship with the prosecution plunged due to the Cho Kuk incident, [the government] began to reform the prosecution service [out of] partisan interests, but nothing was really achieved or appealed to the public, and [instead] only caused a commotion throughout the year.”

With the prosecution service coming after the Democratic Party’s own figures, such as Cho Kuk and Choo Mi-ae, the Moon Jae-in administration greatly stepped up its quest to finalize what it saw as long-overdue reforms to prosecutors’ powers.

However, conflicts between the minister of justice and the prosecutor general made headlines every day, contributing to prosecutorial reform fatigue among the public. At the time, the Democratic Party also criticized the back-and-forth fighting, arguing that it was unnecessarily boosting Yoon’s presence in the public sphere.

The renewed calls for prosecution reform coming from Democrats after losing the presidential election in March of this year were in part a move to shift into gear the party’s policy clarity rather than lingering on the debate over who was responsible for them losing control of the Blue House.

“The party intends to unwaveringly carry out reform on issues raised as the last legislative task of the Moon Jae-in administration including prosecution reform and investigation into the Daejang neighborhood [development scandal]. Our Democratic Party will make every effort to complete the prosecution reform before the inauguration of the new government.” These were the words of Yun Ho-jung, co-chair of the Democratic Party’s emergency steering committee on March 24.

There were other reasons for an explosive sense of crisis in the ruling party. For one, the prosecution service kicked off investigations aimed at the Moon administration, including one into the so-called blacklist at the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy. For another, it was becoming more likely that senior prosecutor Han Dong-hoon would be named to a key role in the Yoon administration after the prosecutors opted not to charge him with attempting to coerce a reporter at Channel A to reveal information about a political opponent.

Under these circumstances, prosecutorial reform — a cause that once enjoyed strong support — is no longer backed by public opinion.

In a poll carried out on April 13, 2022, by Realmeter on behalf of Energy Kyeongje Sinmun newspaper, 38.2% of respondents supported the Democratic Party’s effort to completely remove the prosecutors’ investigative powers, trailing opposition to the reform (52.1%) by more than 10 points. The margin was even wider among respondents who identified themselves as moderates, with 36.1% in favor of the reform and 55.4% against it.

This automated poll of 1,017 adult men and women around the country was conducted on both mobile phones and landlines with a response rate of 4.4%, a confidence level of 95% and a sampling error of plus or minus 3.1 points.

Even some members of the Democratic Party have been calling for the reform drive to be halted, though that remains a minority opinion. Kim Hae-young, a former member of the party’s supreme council, said, “I think the Democratic Party’s rush to complete prosecutorial reform is framed either as ‘battling the villains’ or ‘circling the wagons.’ Since those two viewpoints are providing the main impetus, the party hasn’t been able to offer a metanarrative that’s appropriate for this time.”

According to Kim, the problem is the tendency to view the People Power Party (PPP) or the prosecution service as “villains” who must be crushed or to identify certain members of the party as sacrosanct figures who must be defended.

Cho Eung-cheon, a lawmaker and member of the Democratic Party’s emergency steering committee, has said during radio interviews and in Facebook posts that he supports separating investigation from indictment but noted the importance of what direction that reform takes. Cho is worried that no decision has been made about what to do with the powers of investigation after they’re taken from the prosecutors.

Another concerned member of the emergency steering committee is lawmaker Lee So-young. “Our prosecutorial reform campaign had a lot of public support when it first began, but it gradually lost support. Regret and remorse need to inform the direction and process of prosecutorial reform so that we don’t repeat the same mistakes,” she said.

The problem is that it’s not easy for people to share such opinions within the party.

“Who would want to voice dissent after the lawmaker Keum Tae-sup was disciplined for abstaining from the vote on the Corruption Investigation Office for High-ranking Officials and when people are still getting attacked by [reform] supporters today? Since the presidential election, lawmakers have been inundated with phone calls, emails and letters from party members asking them to move forward with removing the prosecutors’ investigative powers. Without any viable alternative, it’s not easy to be a contrarian,” said one lawmaker in the Democratic Party.

Since the justification for reform has been twisted to meet political expediency, it’s only inevitable that the nuts and bolts of reform have been sketchy. The party hasn’t even bothered to evaluate or incorporate sharp criticism about the adjustment of the police and prosecutors’ investigative powers that dates back to January 2021.

“If earlier institutional reforms haven’t gotten their intended results, there should be a precise diagnosis of the cause and an attempt to institute further reforms to make improvements. A radical and unilateral attempt to take away the prosecutors’ powers of investigation without allocating enough time for debate or listening to the opinions of experts and legal groups cannot be justified, nor does it serve the national interest. In fact, it’s likely to create a major and long-lasting vacuum in the criminal and judicial system,” the Korean Bar Association said.

Even People’s Solidarity for Participatory Democracy (PSPD), a civic group that has played a pioneering role in prosecution reform, said that “reform of the criminal and judicial system clearly should not be rushed” and that “separating the powers of investigation and indictment needs to be discussed on an organizational level in terms of the big picture of prosecutorial reform.” That opinion should be interpreted in terms of the PSPD’s position that “reorganization of the criminal and judicial system is urgently needed and work on prosecutorial reform needs to continue and to be consistent.”

Removing the prosecutors’ investigative powers is the beginning, not the endExperts say the problem lies in the fact that the initial drive for prosecutorial reform focused exclusively on taking away the prosecutors’ investigative powers.

“In the entire process of prosecutorial reform, the government has been completely focused on weakening the power of the prosecution service without defining proper objectives or the values it seeks,” observed Han Sang-hie, a professor at the law school at Konkuk University.

According to Han, the government was preoccupied with the prosecutors’ investigative powers, even though the prosecutors’ famed omnipotence actually derives from the organization itself, which is based on the concept of an organic whole in which each prosecutor carries out orders handed down from above.

“You might say the prosecution service has two problems: one is how it’s organized, and the other is its investigative powers. If those powers are regarded as the problem, handing them to the police will only give the police inordinate power over the state, and handing them to an office for investigating serious crimes will give that office inordinate power,” Han observed.

“We need to change the organization of the prosecutors by revising laws such as Article 7 of the Prosecutors’ Office Act, which says that prosecutors must obey the direction and oversight of their superiors when conducting prosecutorial business. But we also need to think about how to control the police, who will become more powerful when they gain investigative powers.”

There are others who think the important thing is getting started on reform, no matter how imperfect it may be. According to that perspective, the bill should be passed first, and its wrinkles ironed out later.

But given the extreme conflict between the ruling and opposition parties during the legislative process, not even that approach may be practical.

On Thursday, the PPP announced that it plans to boycott a special committee on judicial reform that’s supposed to set up an office for investigating serious crimes. That was just one day after the bill to separate the powers of investigation and indictment was tabled on the floor of the National Assembly.

An agreement between the Democratic Party and the PPP brokered by National Assembly Speaker Park Byeong-seug stated that the two sides would set up a special committee on judicial reform to hold a detailed discussion of the judicial system as a whole, including the proposed serious crime investigative office, which has been dubbed a Korean version of the FBI.

Kweon Seong-dong, floor leader of the PPP, said that the party “cannot cooperate” on the committee. “Since the Democratic Party is ramming through a bill to strip the prosecution service of its investigative powers, our agreement about setting up a special committee for judicial reform has been revoked, too,” he explained.

While it was the PPP that reneged on that agreement, the Democratic Party is not without fault. It resorted to sneaky tactics, including technical maneuvers involving lawmakers Yang Hyang-ja and Min Hyung-bae, to shepherd the bill through the National Assembly’s Legislation and Judiciary Committee while trampling on the spirit of the National Assembly Act.

PPP stonewalling on the special committee on judicial reform will disrupt efforts to set up the serious crime investigative office to take over the investigative powers forfeited by the prosecutors. The two parties had agreed that if the special committee reached a decision to set up such an office, the prosecutors would have to give up direct investigative authority over the last two major categories of crimes under their jurisdiction — namely, corruption and economic crimes.

If the serious crime investigative office isn’t able to begin operations on time, it will certainly throw Korea’s investigative regime into disorder.

“If the special committee on judicial reform were to operate normally, it might be seen as a step forward, albeit insufficient and challenging. But in the current situation, the police might be given too much power while the serious crime investigative office is hardly given any even if the committee does its work. Measures need to be taken to disperse the authority of each investigative body,” said Han Sang-hie, the professor.

The Moon administration has been bookended by prosecutors. After a five-year “war with the prosecution service” that has left the prosecutorial reform campaign in tatters, the bill to separate investigation from indictment has been promulgated at a Cabinet meeting by Moon.

When asked whether that should be seen as a victory, a multi-term lawmaker from the Democratic Party heaved a sigh.

“We had to take this opportunity to separate the powers of investigation and indictment. Beyond the possibility of politically vindictive investigations [after Yoon becomes president], we won’t get another chance to do this,” the lawmaker said.

“But it is a shame. In the past, many Koreans were horrified by the power of the prosecution service because of various incidents, including the death of former president Roh Moo-hyun. But I think people have gotten sick of the issue of prosecutorial reform over the past five years. That’s something we’ll have to deal with.”

By Um Ji-won, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis![[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track? [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/1617144616798244.jpg) [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

Most viewed articles

- 1Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors

- 2[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- 3Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023

- 4Value of Korean won down 7.3% in 2024, a steeper plunge than during 2008 crisis

- 5Thursday to mark start of resignations by senior doctors amid standoff with government

- 6Two factors that’ll decide if Korea’s economy keeps on its upward trend

- 7[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 8Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 9First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 10Why Kim Jong-un is scrapping the term ‘Day of the Sun’ and toning down fanfare for predecessors