hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

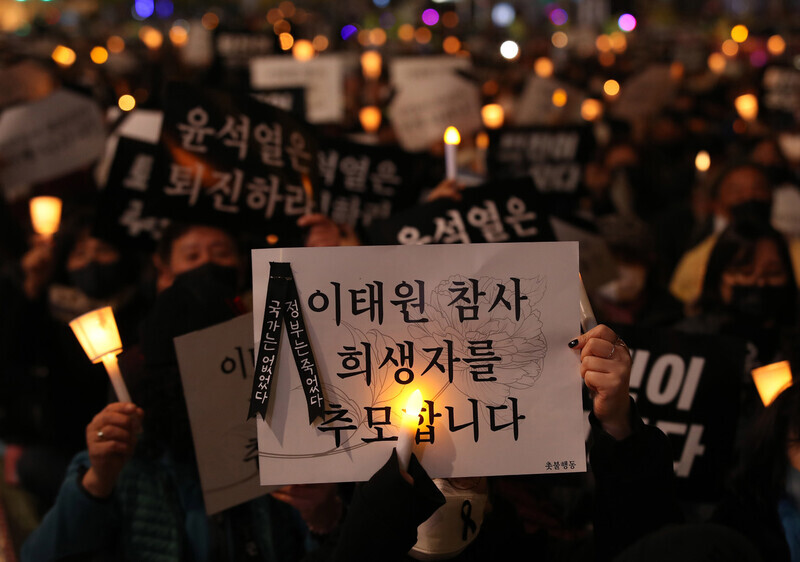

Calls for parliamentary probe into Itaewon disaster meet pushback from ruling party

For a week now, the special investigations office at South Korea’s National Police Agency (NPA) has been stuck at the internal stage of its investigation, which is focused on recreating the actions of the police leadership on the day of the deadly crowd crush in Seoul’s Itaewon neighborhood.

Even granting that the police investigation is still in its initial stage, legal experts and politicians object that the investigation will be of limited utility in dealing with the failure of Korea’s disaster response control towers, including the Ministry of the Interior and Safety and the presidential office, as long as it’s only considering whether the police leadership can be charged for dereliction of duty.

Since it has become clear that the Itaewon disaster was largely due to inaction by the authorities, there’s a growing need for the National Assembly to launch a probe to reassess and improve the government disaster response system, which was last updated after the tragic sinking of the Sewol ferry eight years ago. But the ruling People Power Party (PPP) remains firm in its position that the police investigation should be completed first.

The NPA’s special investigations office (led by Superintendent General Son Je-han) reinforced its investigation team and public relations team on Sunday by adding a team from the NPA’s serious crime investigation section and a senior superintendent.

The special investigations office was set up on orders from NPA Commissioner General Yoon Hee-keun on Tuesday. Amid doubts about whether the police could be trusted to investigate themselves, the investigations office has been piecing together the reports received and the orders given at each hour on the day of the tragedy by people at situation rooms at all levels, by former Yongsan police chief Lee Im-jae; Kim Gwang-ho, head of the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency, and Yoon Hee-keun, using material received from the NPA’s special auditing team. At the same time, the investigations office is assessing whether these officials performed their duties properly and whether any of them were away from the job at the time.

The office’s investigation will inevitably take time to reach conclusions. Given the scale of a disaster that took the lives of 156 people, there’s a vast amount of material to review in connection with the subjects of the investigation.

This investigation is also clearly limited in its ability to figure out the overarching cause of the disaster. Because the police are exploring criminal responsibility for such charges as negligent homicide on the job and dereliction of duty, they’re operating under strict evidentiary standards for determining cause and effect.

Even officials who responded poorly may be excluded from the investigation because criminal prosecution is impractical or because their behavior didn’t violate any legal statutes.

Furthermore, the materials, testimony and internal government records that are essential for assessing and improving systems aren’t typically made public in such investigations.

And if accusations are later raised about wrongdoing being downplayed or covered up, the whole case might have to be brought up again for another investigation.

“Compared to the investigation into the Sewol tragedy, the information that has emerged so far suggests that the Yongsan Police Station and the Seoul Metropolitan Police Agency are the only police bodies that could be held responsible for the lack of a preliminary security plan and the tardy response to reports on 112 [the emergency hotline]. In the end, a police investigation isn’t likely to determine whether control towers such as the Ministry of Interior and Safety and the presidential office were functioning properly in a disaster situation,” said a lawyer and former prosecutor with considerable experience investigating large-scale disasters.

When it comes to matters that are directly connected to public safety but are hard to determine or resolve through a criminal investigation, the lawyer said, a parliamentary probe is needed to identify cause, assign responsibility and devise systemic improvements. For that reason, a parliamentary probe has been carried out during every large-scale preventable disaster in Korean society, including the collapse of the Sampoong Department Store in 1995, the sinking of the Sewol ferry in 2014, and deaths caused by humidifier disinfectant in 2016.

Nevertheless, the PPP holds that a parliamentary probe is not a priority. “Holding a parliamentary probe now would only interfere with the investigation. The time to discuss that is if the investigation proves inadequate and public suspicions remain,” the party said.

In contrast, the Democratic Party and the Justice Party are planning to submit a request for a parliamentary probe on the floor of the National Assembly on Thursday. A parliamentary probe can be carried out at the request of at least one-quarter of lawmakers. But since a probe requires cooperation from the ruling party, it’s typically pursued with bilateral consensus.

Carrying out a criminal investigation and parliamentary probe at the same time can also create synergy. That was the case after the Sewol sinking and during the influence-peddling scandal that led to the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye.

While the Saenuri Party (currently known as the PPP) resisted calls for a parliamentary probe by victims’ families, the opposition party and civic society after the Sewol ferry sinking, a 90-day probe was eventually launched on June 2, 2014, nearly 50 days after the tragedy occurred.

While the probe’s findings weren’t ratified because of obstruction by the government and the ruling party, it did achieve some results. The recording transcripts and other materials submitted by such organizations as the Coast Guard revealed the poor response of the crisis management center at the Blue House’s National Security Office, and the question of what Park was doing during the seven hours after the accident was brought into the public debate.

It's true that parliamentary probes can fizzle out because of political squabbling or can be less efficient because of overlaps with the criminal investigation. But experts argue that criminal investigations should be viewed as separate from parliamentary probes, which are a method of legislative oversight over the executive branch in presidential systems.

Concerns about political bickering and retreading the same ground could be addressed if the ruling and opposition parties sat down to hammer out the specific objectives and scope of the probe.

“Political responsibility is different from legal responsibility. There’s no reason for the National Assembly to wait until the police investigation is over. The National Assembly should obviously examine what government shortcomings may have been revealed by the occurrence of the disaster and the response to it, separately from criminal responsibility,” said Jang Seung-jin, a professor of political science at Kookmin University.

“The National Assembly has the duty of fulfilling the role entrusted by voters. Considering that we’re not likely to learn the results of the investigation for a while, it would be irresponsible for lawmakers to just sit on their hands,” said Kang Woo-jin, a professor of political science at Kyungpook National University.

“This should be viewed as a matter of state and public interest, rather than through the lens of specific factions and parties. Political action from President Yoon Suk-yeol is needed to accept the parliamentary probe and move to the next phase.”

By Jang Na-rye, staff reporter; Shin Min-jung, staff reporter; Chai Yoon-tae, staff reporter; Nam Ji-hyeon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 2Amid US-China clash, Korea must remember its failures in the 19th century, advises scholar

- 3[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 4Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 5[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 6S. Korean first lady likely to face questioning by prosecutors over Dior handbag scandal

- 7Lee Jung-jae of “Squid Game” named on A100 list of most influential Asian Pacific leaders

- 8After 2 years in office, Yoon’s promises of fairness, common sense ring hollow

- 9[Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- 1060% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage