hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

For survivor, Jeju April 3 massacre is a living reality, not dead history

“I can still see it clearly. I saw what happened and experienced it first-hand when I was just 6 years old, how could I forget it? It’s seared into my eyes.”

These were the words spoken in a trembling voice by Yang Su-ja, 81, whom I met at her house in Ildo No. 2 neighborhood in Jeju City on March 27. Every time she thinks of that day, she becomes breathless. For her, the events touched off in Jeju on April 3, 1948, are not dead history from 75 years ago, but a living fact that shapes her present reality.

After witnessing her entire family be massacred at the age of 6, Yang’s life has felt suffocating. When she wakes up, the events of that day come to mind as if they had happened yesterday and her heart beats fast whenever she hears any news related to the uprising and massacre on TV.

In March 2020, Yang was belatedly recognized as disabled due to the injuries she sustained during the bloody period in Jeju, a fact that brought some much-needed relief. Nevertheless, she still suffers from severe trauma.

“Even my tears have dried up now,” Yang says. “I often want to avoid places where many people gather. I can't breathe when I think about it. Living itself has been suffocating.”

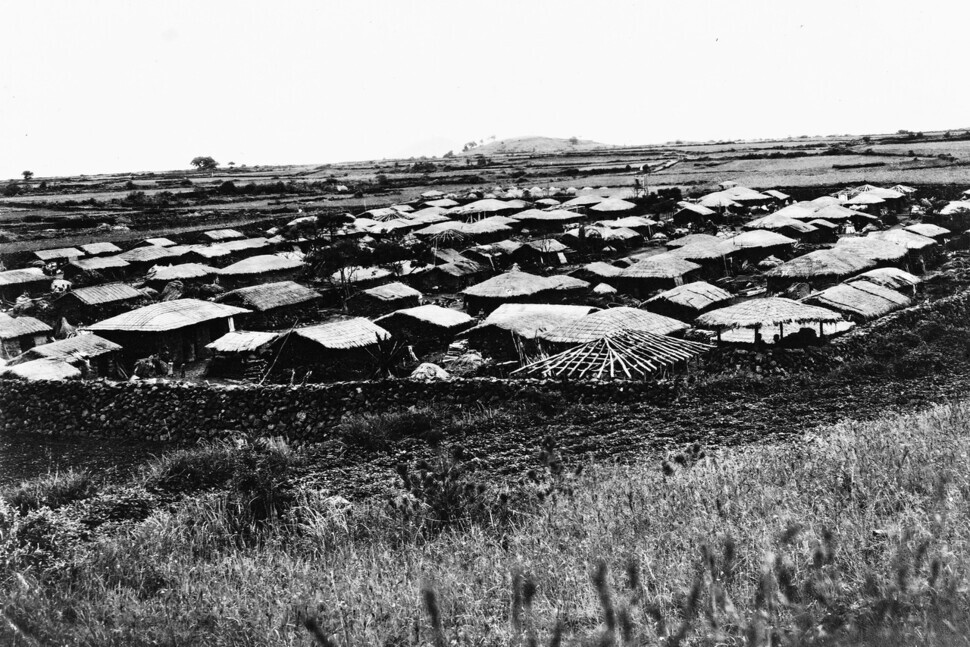

On Feb. 3, 1949, a military punitive expedition stormed into the Yang family’s home, a hut they built in a pine field on the outskirts of Nohyeong (near present-day Jeju High School).

Nohyeong, now one of the most bustling areas in Jeju, was also the village that recorded the most casualties from the April 3 Incident in Jeju among all administrative divisions.

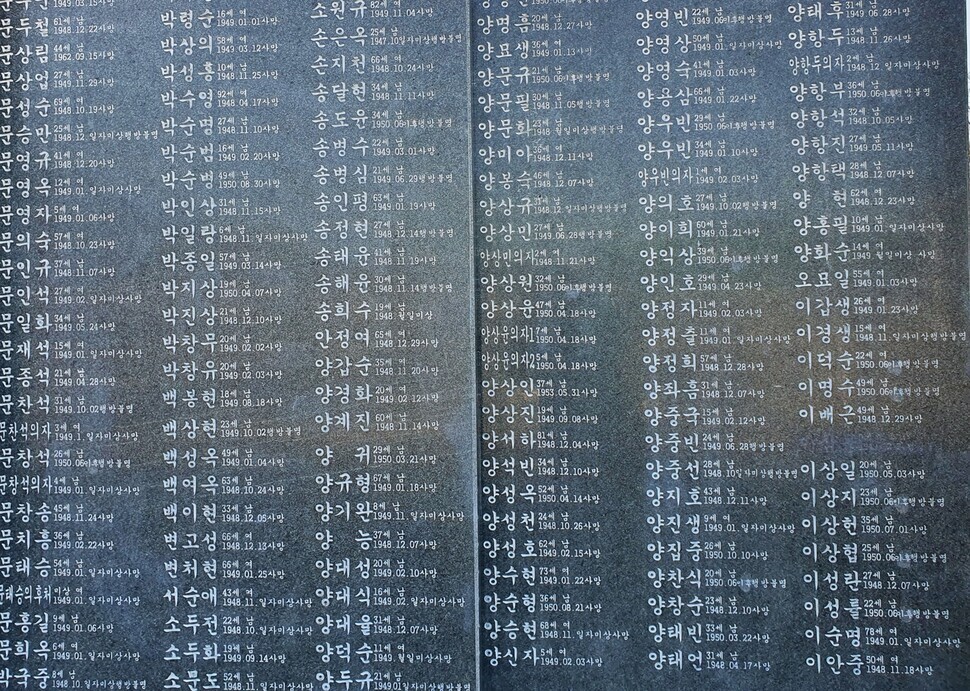

According to the Jeju 4ㆍ3 Peace Foundation’s “Additional Jeju April 3 Incident Investigation Report” published in 2019, the village of Nohyeong in the town of Jeju had the highest death toll at 538, including 370 dead, 156 missing, 11 incarcerated, and 1 disabled.

Troops belonging to the 9th Regiment began razing the village between Nov. 19 and 20, 1948, just two days after martial law was declared. The village went up in flames, taking the lives of numerous villagers.

According to local publication Nohyeon Gazette (2005), among the six rural villages in Nohyeong, around 260 people from 61 households lived in the village of Jeongjon, which the Yang family called home, at the time of the April 3 uprising and massacre. Among them, 120 were killed, including the entirety of her aunt's family. Four generations of her aunt’s family, from her grandfather-in-law to her children, were massacred at once.

The straw-thatched roof house in Jeongjon where the Yang family lived was also burned to the ground. A total of seven people lived in the house, including Yang’s grandmother (Kim Sa-il, 64 at the time), father (Yang Woo-bin, 27), mother (Hyeon Kyung-ok, 29), older sister (Yang Jeong-ja, 10), younger sister (Yang Shin-ja, 4), and her 2- or 3-month-old younger brother.

On Dec. 10, 1948, after their home was burnt down, Yang’s grandmother was shot and killed by punitive forces while working in the fields.

With nowhere else to go, the remaining six family members headed to their grandmother's house near Altteureu Airfield (now Jeju Airport). When they got there, however, locals stopped them from entering the house. The neighbors thought Yang’s family were insurgents from the mountains. Had they come before their home was burnt down, they wouldn’t have encountered such suspicion. But they had arrived too late.

They went on the move in the middle of the icy winter. They had no way of knowing when or where the military or police could show up and arrest them, but they had no choice.

Yang and her older sister walked, carrying their younger siblings on their backs or holding them. They headed to a family-owned pine tree field on the outskirts of Nohyeong.

“No matter how much my father begged, they would not let us in, calling us mountain insurgents, so we went all the way to the pine field. We built a hut and lived there,” Yang recalls.

The hut was small, made with pine collected by cutting trees and tying them together to block the wind out. The six family members lived inside day after day, but their shelter couldn’t keep the winter chill out. But then, something even more frightening than the winter cold found its way to them.

While the sun was still out on Feb. 3, 1949, punitive forces stormed into the Yang family hut. They came while Yang’s father had briefly gone out. Only 6 at the time, Yang committed to memory what she witnessed that fateful day. While she tried to run away from the pain associated with that memory throughout her life, the more she tried to escape it, the more the memory suffocated her.

“First they shot my mother,” she said. “They fired and missed so they fired three times. With the third shot, the bullet hit her neck. Blood splatters if you’re shot in the neck, you know. We were completely covered in blood as it splattered.”

Armed with knives and guns, the punitive forces shot and stabbed Yang and her loved ones. Yang’s older sister was shot in the leg and crumpled into a pile in the snow. The punitive forces thought she was dead and left her as she was.

After her father returned, she took her older sister to a place with people nearby to have her treated, but those houses too were burnt down that night. Her older sister's body was never found. Her younger sister was found dead in their home, still sitting upright.

Yang was stabbed in her left side with a blade and fainted briefly before regaining consciousness. She opened her eyes and looked around. Her younger brother, who was only a few months old at the time — too young to have even been given a name — was dead on the floor, his neck slashed.

Yang remembers the warning the punitive forces gave her that day: “We will kill you again if we come back and find you still alive."

“I still can't forget those words,” she said. “Even now, it’s as if they’re standing here next to me saying them. Although I was young when my mother, older sister, and younger siblings were killed, I directly witnessed those scenes so I can still clearly see them even now. My father was an only son and so was my younger brother. The newborn baby must have been so adorable.”

That is how Feb. 3 went. But that wasn't the end of the family’s tragedy. Yang’s father, who had howled in anguish and collected the bodies of his dead wife and children, had no time to grieve. He had to at least try and save his daughter, who was losing blood.

Braving the midwinter cold, Yang’s father walked down the snowy road from the hut to Samseonghyeol carrying his daughter on his back.

The distance was less than 6 kilometers, but it took around three hours on foot. Still, he had no way of knowing when or where the punitive forces or Northwest Youth Association might attack.

As they arrived at the grave next to Samseonghyeol Shrine, he told his young daughter, “You stay here while I go get a blanket.”

“Father, I’ll go with you,” she insisted. So he pretended to go to sleep, holding her in his arms.

Graves in Jeju are mostly surrounded by square stone walls that are meant to prevent cows and horses from wandering in. When Su-ja woke up, her father was nowhere to be seen. It was the last time she ever saw him.

All of a sudden, she was gripped by fear. It was a bitterly cold day. She had some boiled barley rice in a small basket and a pair of geta (Japanese shoes) with her grandmother’s address written on them.

For three days, she remained weeping inside the stone walls. The snow kept falling.

Her body was black and blue from the cold, but still she stayed alone for three days behind the walls. Expecting her father to return, she never thought to go anywhere else.

Next to the stone walls of a deserted grave, the girl sat and wept. Her cries were carried along with the sound of the cold winter wind. Finally, the crying stopped, and stillness descended — a stillness that seemed to exist somewhere in between this world and the next.

“I remember there was a guard hut,” she said. “Someone from the guard post came over. They couldn’t tell if the sound was a person or a wild animal.

“You can imagine how shocked he was to see me. I was crying with my body all swollen, black and blue. I was like something in between a person and a ghost.”

Seeing the address on her shoes, residents took her to her grandmother’s house. There, she ended up having to do various household chores, and she was sometimes beaten for no reason.

She might have suffered less if she had been sent to an orphanage, she said. She also had to be wary when eating meals.

“If I ate the food, I’d get beaten for ‘eating too much,’” she recalled. “So I would scoop some rice and soup into a wooden bowl and hide it in the shed. Then, when my grandmother went out, I’d gulp the whole thing down without chewing.

“Even today, I never take longer than five minutes to eat. That’s how I lived.”

At the age of 7, she began going out to the fields to pick weeds. It was a much easier time for her when she went on her own to weed the millet field. While grinding beans on her own, she could lie down and rest when she felt too hot or tired — but that was not an option when her grandmother went with her.

“It was hot when I did weeding in the bean field,” she explained. “If I stood up because it was too hot, down came the hoe. She was preventing me from standing up straight because she said it would become a habit. There were times I fainted because I couldn’t stand up and feel the breeze.”

Yang did not envy her peers who went to school. Even envy would have been a luxury.

But she did want to learn to read. She recalls studying “until my eyes were red.”

She went to church in the Jeongtteureu area. She began attending around the age of 10 and continued until she was 19, a year before she married. She managed to go despite her grandmother’s efforts to stop her.

“A woman just needs to know how to make food and open a pot lid,” the grandmother had told her. She would wake her granddaughter at three or four in the morning and have her cook.

After going to the pasture and carting hay in front of the house, she would take a small piece of cardboard and race over to the night school affiliated with her church. She continued going until her second year of middle school. This was how she learned to read.

During her fourth year of elementary school, she was taking math classes with middle school students. To come up with the 5 won in monthly costs, she would collect beans and barley at other pastures or chop trees on the mountains to sell the wood. Any money left over was saved up as seed money for when she married.

Yang desperately missed her father.

“I would be on my way to the stream to get water and see someone who looked like my father, and I would chase after him, thinking it might actually be him,” she remembered.

“But when he continued on past the street where my grandmother lived, I’d realize, ‘Oh, that wasn’t him’ and returned dejectedly to get the water. That happened several times up until I was around 20,” she recalled.

Her grandmother would yell at her for taking so long and beat her for acting out.

A few times, her father appeared to her in dreams. She cried and spoke to him, but he never replied. She would wake up with her pillow sopping wet. The tears she cried there began gathering and festering in her heart.

The father had apparently been captured by the military and police after leaving his daughter behind at the grave near Samseonghyeol. He had been held prisoner at a Jeju boat factory before being let off. But then he was arrested again based on allegations from someone or other.

In July 1949, he was sentenced to life imprisonment by a court-martial. He was sent to Mapo Prison in Seoul; after the Korean War, his whereabouts were unknown.

On March 16, 2021, he was exonerated in a retrial of 335 Jeju April 3 prisoners at the Jeju District Court. Yang had heard from her uncle that her father had been taken to prison during the events of Jeju April 3, but she did not know what his sentence had been.

Speaking to the judge in the courtroom that day, she said, “I knew my father went missing and died, but this is the first I’ve ever heard about a life sentence.”

“My heart aches so much I think it might burst. Thank you for exonerating him,” she added.

Despite her harsh circumstances, Yang wanted to honor her elders in a way she never could do for her own parents. As part of her volunteer activities, she cooked for 12 years at a senior citizens’ center.

In 2020, Yang was recognized as disabled due to the injuries she sustained during the Jeju April 3 Incident, and her entire family, who were all killed, were acknowledged as official victims of the atrocity.

Does she finally feel at peace? Yang still deals with trauma to this day. When she first visited the Jeju 4.3 Peace Park, tears clouded her eyes and shortness of breath made it hard for her to walk. She couldn’t even look at her surroundings. Now, she has gotten slightly used to it. She’s able to go through the park with fewer tears, which makes her feel relieved.

“I don’t like visiting crowded places, and whenever the Jeju April 3 Incident is mentioned on the television I turn it off. I didn’t want to go to the 4.3 Trauma Healing Center, even if they asked me to come. I can still see the incident so clearly, if I wake up in the middle of the night, it’s the first thing I think of. You think I’d have gotten used to it by now, but it is something I will never be able to forget.”

For the child who saw her home burnt down and her family killed, every waking day is April 3.

By Heo Ho-Joon, Jeju correspondent

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 3Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 4No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 51 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 6Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8Marriages nosedived 40% over last 10 years in Korea, a factor in low birth rate

- 9[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 10Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US