hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

US has always pulled troops from Korea unilaterally — is Yoon prepared for it to happen again?

US Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and his close aides continue to hint at a withdrawal of US troops from South Korea.

Elbridge Colby, a potential candidate for national security adviser, served as the deputy assistant secretary of defense for strategy and force development during the former Trump administration. In a Yonhap News interview published recently, Colby said that “US forces on the Peninsula, in my view, should not be held hostage to dealing with the North Korean problem, because that is not the primary issue for the US.”

"The US should be focused on China and the defense of South Korea from China over time,” Colby added.

In an interview with Time magazine published on April 30, Trump remarked about South Korea, “Why would we defend somebody? And we're talking about a very wealthy country. But they're a very wealthy country and why wouldn't they want to pay?”

Since the 2015 Republican primaries, Trump has been spouting the idea that South Korea is a “freeloader” when it comes to defense. In his book published in November 2015, Trump decried the situation of “28,500 wonderful American soldiers on South Korea’s border with North Korea,” saying that they are in “harm’s way.”

“They’re the only thing that is protecting South Korea,” he wrote. “And what do we get from South Korea for it? They sell us products — at a nice profit. They compete with us.”

When critics rebutted that South Korea was paying 920 billion won (US$672.26 million) per year toward stationing US troops in Korea, Trump laughed off the sum as “peanuts.”

In his memoirs published in 2022, former Defense Secretary Mark Esper claims that Trump called for the withdrawal of US troops from South Korea numerous times. Esper also recalls that Secretary of State Mike Pompeo had to dissuade Trump from this position by urging the president to make the withdrawal a priority during his second term. Five years later, Pompeo’s comments to calm the president down may become a reality.

Trump has received plenty of reports on the strategic value of US Forces Korea and on the financial contributions that South Korea has actually made, so why does he continue to accuse Seoul of freeloading?

As a former real estate developer, Trump seems to be utilizing negotiation strategies that exploit the anchoring effect, a psychological phenomenon where a person’s perceptions and judgment are influenced by an “anchor,” or specific reference point — even if it’s irrelevant to the wider discussion.

When Trump was president, he demanded that South Korea increase its burden-sharing contribution for US Forces Korea from 1 trillion won (US$730.7 million) to 5 trillion (US$3.65 billion). This could be seen as an example of the anchoring effect. While the fivefold increase was absurd, Trump likely determined that starting negotiations with a fixed price demand was in his favor. Let’s say that Washington and Seoul agree on 2 trillion won (US$1.46 billion). This would be an increase of 100% from the original 1 trillion, but compared to 5 trillion, it looks like a good deal.

When Trump threatens to simply walk away from negotiations if the other side doesn’t agree to his demands, the anchoring effect is amplified. This is pretty much what happened when Trump threatened to pull US troops from Korea during defense cost negotiations with Seoul.

To avoid falling victim to the anchoring effect, we need to prepare with our own standards and counter-arguments, backed up by objective data, before negotiations even begin. South Korea needs to inform the American people how Seoul contributes to US Forces Korea — and not just financially.

South Korea contributes to US Forces Korea both directly and indirectly. Direct support takes the form of cash or spot assets delivered to US troops stationed in Korea. South Korea’s burden-sharing contributions, however, take many forms. Seoul also pays for Korean Augmentation to the United States Army (KATUSA), the maintenance of the roads surrounding the US base in Pyeongtaek, and subsidies for the surrounding region in Pyeongtaek. When counting the original 1.18 trillion won (US$862,000) that South Korea directly pays to US Forces Korea, the actual figure from all other subsidies and supports makes the total closer to 2.1 trillion won (US$1.53 billion)

Indirect support takes the form of offering land, tax incentives, and exempting electric bills, telecommunications bills and other utilities. South Korea also exempts or drastically reduces road tolls, airport fees, and port fees for US troops. This indirect support amounts to 1.3 trillion won per year (US$949.5 million).

When combining both direct and indirect support, the annual cost that South Korea bears for hosting US troops is well over 3 trillion won (US$2.19 billion). Considering it takes around 1 trillion won to build a single Aegis destroyer, South Korea is essentially forfeiting the cost of three Aegis destroyers per year to host US troops.

If Trump is elected, not only would it affect defense cost negotiations, but Trump would likely call for revisions to the South Korea-US military alliance to bolster Washington’s ability to contain Beijing. During a press conference to commemorate two years in office on Thursday, South Korean President Yoon Suk-yeol declared that “the South Korea-US alliance receives strong support from both the American government and people, from both parties in the US Congress, and from the current administration.”

“The robust alliance and partnership between the US and South Korea will remain unchanged,” Yoon added.

Despite Yoon’s claims, however, the issue of US troops in Korea ultimately rests with Washington — and Washington will ultimately base its decisions on its diplomatic interests and strategic judgments concerning the larger region of Northeast Asia. That is how South Korea-US relations have played out since Korea’s liberation from Japan in 1945.

After occupying South Korea following the defeat of Japan in World War II, US troops withdrew completely from the peninsula in June 1949. The outbreak of the Korean War in 1950 drastically changed this situation. The US troop presence in Korea grew to as numerous as 330,000 during the war. Following the signing of the Armistice Agreement, the US troop presence was reduced to 85,000 in 1954.

In 1970 the US pulled the 7th Infantry Division, removing 18,000 troops from Korea. In 1977, President Jimmy Carter pulled an additional 6,000. In 1990, an additional 15,000 troops withdrew from Korea. In 2005, an additional 10,000 troops were withdrawn. This makes for six troop withdrawals. The general historical trend has been one of withdrawal or troop reduction. Every time the US has pulled troops from Korea, it has done so without reaching an agreement with South Korea — or at the very least without any meaningful negotiations.

On March 8, 1966, during a National Assembly meeting on the issue of sending Korean troops to Vietnam, South Korean Prime Minister Chung Il-kwon announced, “We have written received assurances from the US that Washington will continue to maintain its current troop presence in South Korea.”

In 1969, US President Richard Nixon declared his doctrine that if a conventional military conflict occurred in Asia, then the parties to the conflict themselves would be responsible for the first line of their own defense. In March 1971, the US unilaterally pulled its 7th Infantry Division from Korea. Ten days later, the US announced that its ping pong team would be visiting China. It was a diplomatic play in order to open relations with Beijing. Normalizing relations with China was part of Washington’s global strategy, and the small power of South Korea was not part of its play.

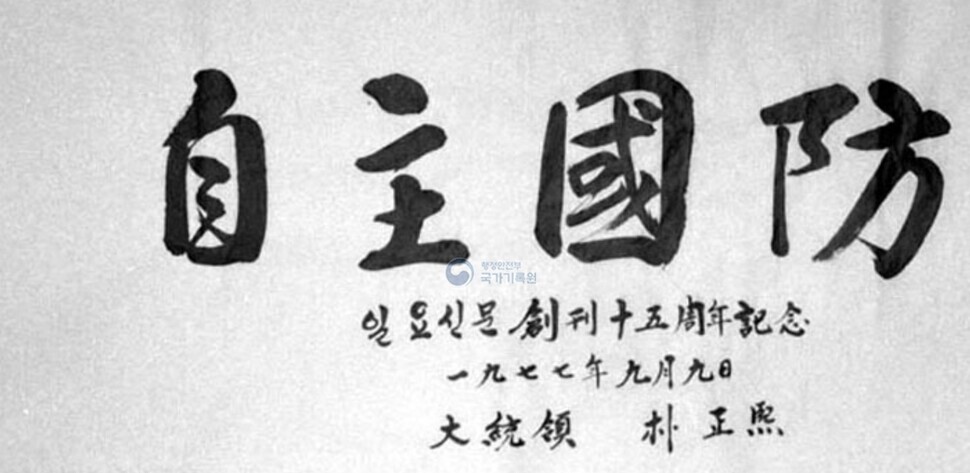

South Korean President Park Chung-hee was so shocked by this betrayal that from 1970 onward, he advocated for self-reliant national defense. He promoted the domestic defense industry, agreed to the July 4 South-North Joint Statement and to dialogue with North Korea, and called for South Korea to develop its own nuclear weapons. If Trump is elected this November and calls for a troop reduction or withdrawal, South Korea may once again be forced to seek defense autonomy, changes in inter-Korean relations, and a reevaluation of its reliance on the US for our defense and weapons, just as Park did in 1970.

Trump’s former adviser, Colby, said, “The idea of South Korea assuming primary responsibility should happen as soon as possible, like now.”

The Trump camp is calling for transferring wartime operational control (OPCON) over Korean troops from Washington to Seoul — something that the Yoon administration had no interest in. If Yoon wants to prepare for the risks posed by Trump, then he needs to start addressing the OPCON issue that he’s been neglecting for the past two years.

By Kwon Hyuk-chul, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0630/9717197068967684.jpg) [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

[Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated![[Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0628/7617195640940814.jpg) [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

[Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

- [Editorial] Workplace hazards can be prevented — why weren’t they this time?

- [Editorial] Seoul failed to use diplomacy with Moscow — now it’s resorting to threats

- [Column] Balloons, drones, wiretapping… Yongsan’s got it all!

- [Editorial] It’s time for us all to rethink our approach to North Korea

- [Column] Why empty gestures matter more than ever

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- 2Dreams of a better life brought them to Korea — then a tragic fire tore them apart

- 3Yoon echoed conspiracy theories about Itaewon disaster, former National Assembly speaker says

- 4[Reportage] On Yeonpyeong Island, residents fear military drills will snowball into war

- 5Son Heung-min’s father, brother accused of child abuse at football academy

- 6Moscow tells Seoul to rethink ‘confrontational course’

- 7[Photo] K-pop: For everyone, everywhere

- 8[Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- 9Nuclear South Korea back up for debate as North cozies up to Russia

- 10‘Disposable’: How illegal temp work practices push migrants in Korea into risky jobs