hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Recollections of the Gwangju Democratization Movement as a taxi driver

Lee Haeng-gi, the 69-year-old chairperson of the May 18 Arrested and Wounded Victims' Group democracy drivers’ committee (formerly the May 18 Gwangju Uprising Association of Drivers for Democracy.), still remembers the number of the taxi he drove 40 years ago: “Pony 7013.” In 1980, over 700 taxis were operating in Gwangju -- 500 corporate, 100 private taxis, and 100 limited-time taxis (permitted to operate only for a set period). Lee’s was a limited-time taxi, a new ’80s-style model.

Even though it was someone else’s property, Lee took pride in his driving, which allowed him to take care of his family.

“Back then, the Kia’s Brisa and Hyundai’s Pony were the new models, and the old taxis were Coronas, Cortinas, and Chevrolets. I drove a limited-time Pony taxi. Cars were rare back then, so you could do well for yourself driving a taxi. I started driving a taxi when I was 21, and I had a bunch of friends and would go out drinking often. It was that kind of a time.”

It was on May 19, 1980, that a whirlpool swept into his ordinary lower middle-class life. He went out that morning as usual after being off-duty the day before. On Geumnam Road, he saw martial law forces searching and stripping university students and beating them with clubs. He’d seen a number of student demonstrations as a cab driver, but it was the first time he’d ever seen this kind of savage suppression. Around lunchtime, he headed to the public bus terminal to wait for passengers. Five to six other taxi drivers who had arrived ahead of him were standing there talking about how the martial law forces were beating students and citizens alike and then dragging them to the provincial office.

“Taxi drivers travel around the entire Gwangju area, so information travels quickly,” he said. “One person said they saw soldiers beating someone in Baegun [a neighborhood of Gwangju], another one in Gyerim [another neighborhood]. I could feel the anger boiling up inside of me. But at that point, I still thought that we [taxi drivers] would be all right. It was in the afternoon that everything went to hell.”

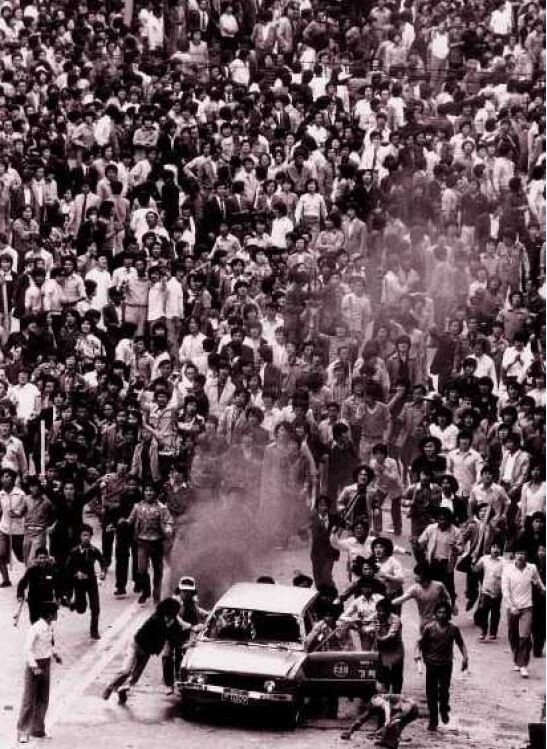

The scattered demonstrations began to expand around Geumnam Road. Over and over, demonstrators would hurl stones at martial law forces, and the soldiers would chase after them. With fixed bayonets, the martial law forces identified one demonstrator as the apparent ringleader, pursuing and capturing him. Soldiers who failed to catch demonstrators would question passing citizens about them; if they gave the wrong answer, they would be hit with the butt of a gun. Lee felt his rage build after seeing a senior citizen being struck.

Other taxi drivers who were angry like Lee opened up their passenger side doors to allow fleeing demonstrators inside, traveling another 100m or so before letting them out again. Some taxis carried as many as 10 or so different demonstrators. Other drivers loaded their cabs with stones to give to demonstrators. This did not escape the martial law forces’ attention.

The soldiers randomly ordered taxis to stop. Any young people they had inside were dragged out. Any taxi driver who was stopped was struck with the butt of a gun. The martial law forces tried to stop one Brisa taxi carrying a student in front of Gwangju Station, but the driver ignored them and kept going. A soldier at the checkpoint jabbed the car’s door with a gun that had a fixed bayonet. The gun dangled from the taxi for around 10m before falling off. Fortunately, both driver and passenger escaped unscathed.

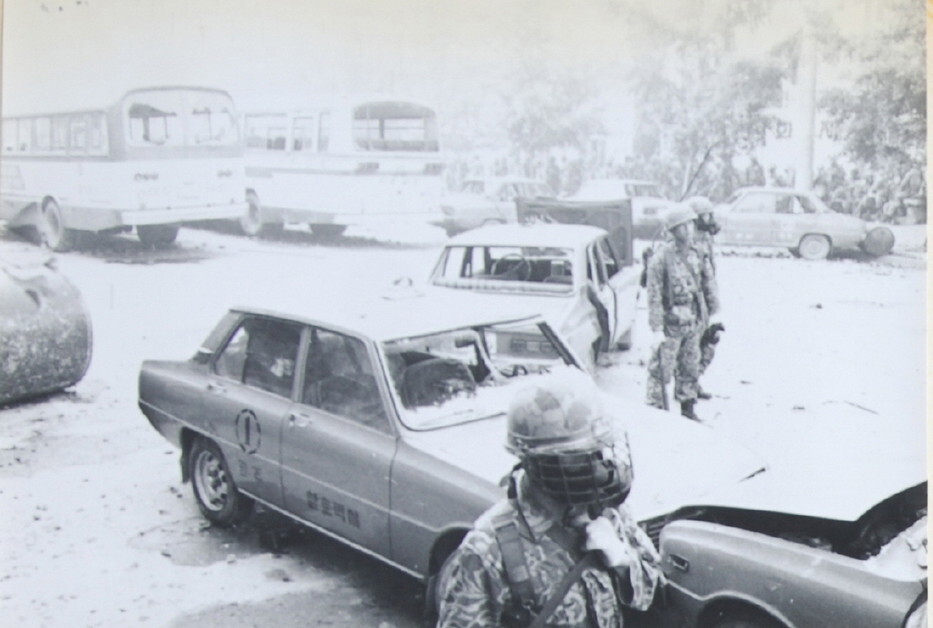

Using cars as barricades and weapons against the martial law forcesUnable to abandon his livelihood, Lee put the chaos of the day before behind him and headed out for work again on the morning of May 20. He headed toward the area in front of Mudeung Stadium after hearing that express buses were letting their passengers out there, unable to enter the downtown area because of the soldiers’ cordon. The assembled taxi drivers decided that they couldn’t just stand by and do nothing. They suggested using their cars to drive back the martial law forces and rescue the citizens captured at the provincial office.

“The public’s spirit was already broken because of the soldiers’ brutality. They were all going to die if we didn’t do something. We got together and said, ‘Those [soldiers] have their bayonets fixed, so let’s use our cars to drive them back. Let’s recapture the provincial office.’ Imagine how pissed off the soldiers were after hearing about taxi drivers helping the demonstrators. I wasn’t thinking about my family at that point.”

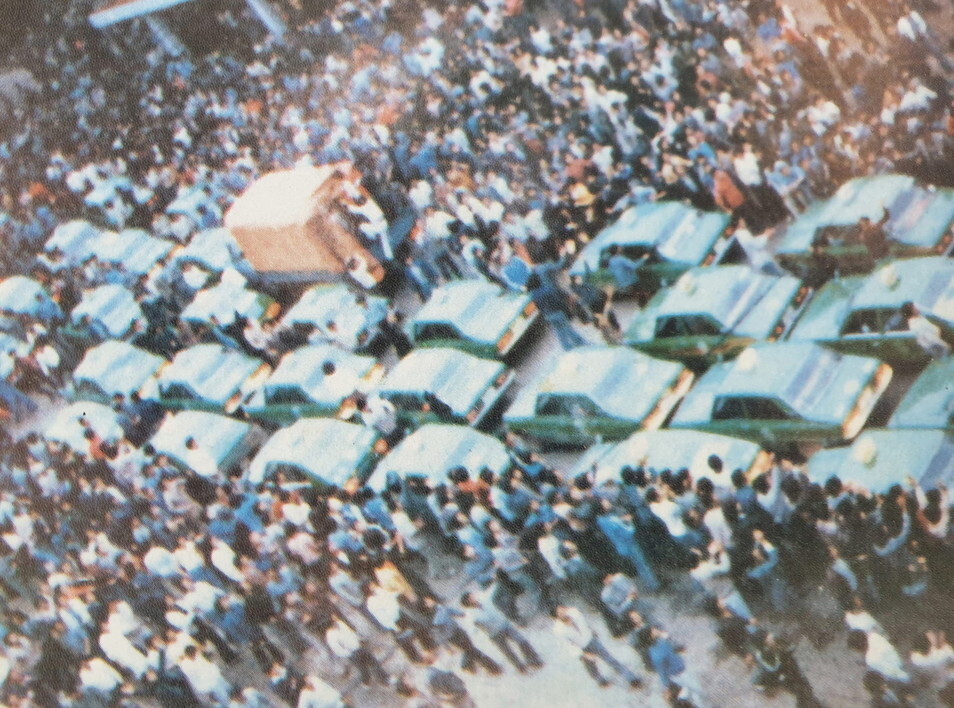

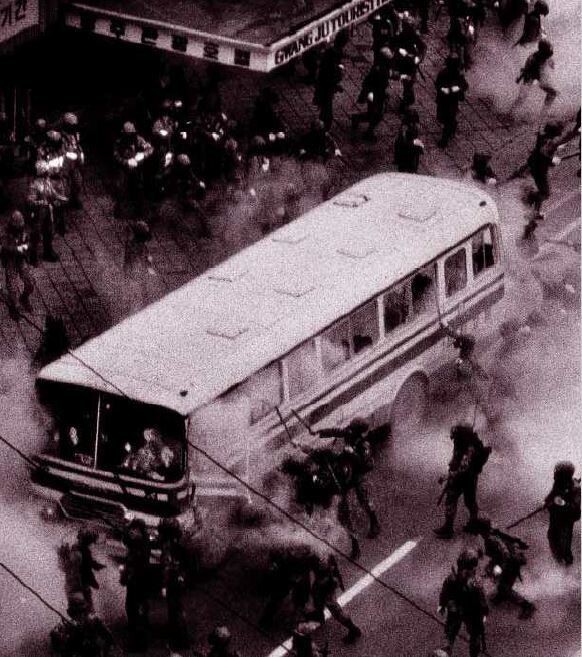

It was the beginning of the vehicle demonstration, which re-stoked the fading embers of the democratization movement. Lee and the other taxi drivers called on their colleagues to arrive at Mudeung Stadium by around 6 pm. Dozens of taxis headed toward the provincial office, splitting off in the directions of Yudong Intersection and the public bus terminal. Lee joined the ranks heading to Yudong Intersection.

“Two kilometers between Yudong Intersection and the provincial office are a straight shot. And with dozens of taxis taking part, the response from the public was positive. They put on their lights, sounded their horns, and drove slowly to match the pace of the people walking. Some of the drivers had no idea what was going on and got pulled in, and they ended up joining the demonstration when they couldn’t get out because of the people surrounding us.”

As he arrived at the intersection in front of Gwangju Station, citizens arrived with a city bus, using it to lead the caravan from the front. As ordinary cars had joined the caravan, it swelled to over 200 vehicles. But the price to be paid for this peaceful vehicle demonstration was steep. With just 300m left to the provincial office, martial law forces watching over the front of the Jeonil Building began attempting to stop the caravan. Dozens of tear gas canisters were fired off all at once, shrouding the road in a fog so thick that no one could see. Club-wielding martial law forces began chasing and striking people at random. The citizens quickly scattered. The cars at the back of the caravan were able to turn around and escape, but the ones at the front could not. Most of the taxi drivers abandoned their vehicles and fled; others, unable to give up on their livelihood, cowered inside their cabs until the rain of cudgels came down. Lee got out of his taxi and escaped the fray by fleeing into a side street by Cheil Bank.

After this incident, the uprising intensified, and the taxi drivers became full-fledged participants in the demonstrations. Lee joined the demonstrators in an attempt to take back the provincial office. Working with two young demonstrators at the entrance of Chungjang Road around 9 pm, he attempted to attach a torch to a Brisa taxi and then place a stone on the gas pedal and send it toward the provincial office. But the car did not travel in a straight line, and ended up running into a tree by the side of the road. Lee went over to the car and straightened the steering wheel. Just as he was closing the door, he felt an intense pain in the back of his head and dropped to the ground. He’d been ambushed by a martial law soldier who had been observing him from a distance.

Dragged to the provincial office, where a soldier caused Lee a permanent spinal injurySemiconscious, Lee was dragged away. He heard a soldier by the provincial office fence saying, “This one’s an arsonist,” at which point he blacked out. When he came to, it was the next morning (May 21), and he was in an office at the old South Jeolla Police Agency. Three of his front teeth were broken, and his face was covered in blood. Around 30 other citizens were in the same room; all of them were in more or less the same battered shape as Lee.

Every two to three minutes, soldiers would drag more people into the room; each time they left, they would mercilessly assault people. One of the soldiers stamped the heel of his combat boot into the spines of the prisoners as they lay on their stomachs. “I’m going to make sure you’re crippled for life if you do survive,” he said. It was at his time that Lee suffered a fractured vertebra. Seeing this, police officers who had been watching over the office gave him a wad of newspapers, telling him to press it against his back. Later on, a soldier saw the newspaper and struck one of the police officers, demanding to know who had given it to him. They were brutal times.

That day, Lee experienced a mortal fear that he will never forget. Around lunchtime, he heard the sound of a helicopter, followed shortly by gunfire. The soldiers had opened fire on the public in front of the provincial office. Unable to move and unaware of the situation outside, Lee was sure he was about to die. A police officer pointed to the bathroom window and told him to flee, but he was unable to move with his injured vertebra. Fortunately for him, he was rescued by the citizens’ militia after the martial law forces retreated to the outskirts of the city, and was able to return home.

“It’s pure luck that I survived after being caught in the act. I was so scared then that even now, I just have to hear a low ringing like the sound of a gong and my heart starts racing because it reminds me of gunfire.”

Lee managed to reunite with his family, but going to a hospital for treatment was out of the question. Recalling the soldier’s words “this one’s an arsonist,” he decided to take refuge at home. Unable to receive treatment, he ended up suffering a disability when his broken vertebra fused improperly.

Unable to work after becoming disabledAfter his body had healed to some extent, Lee returned to work, but his record as a protester kept him from getting hired as a full-time driver. Instead, he had to work as a standby, only taking the wheel when one of the regular drivers had a day off. One day in 1987, he was driving a fare when his right leg went numb. He couldn’t hit the brakes and almost got into a serious accident. After deciding that he shouldn’t be on the road anymore, he moved to Hampyeong County, South Jeolla Province, where he became a farmer.

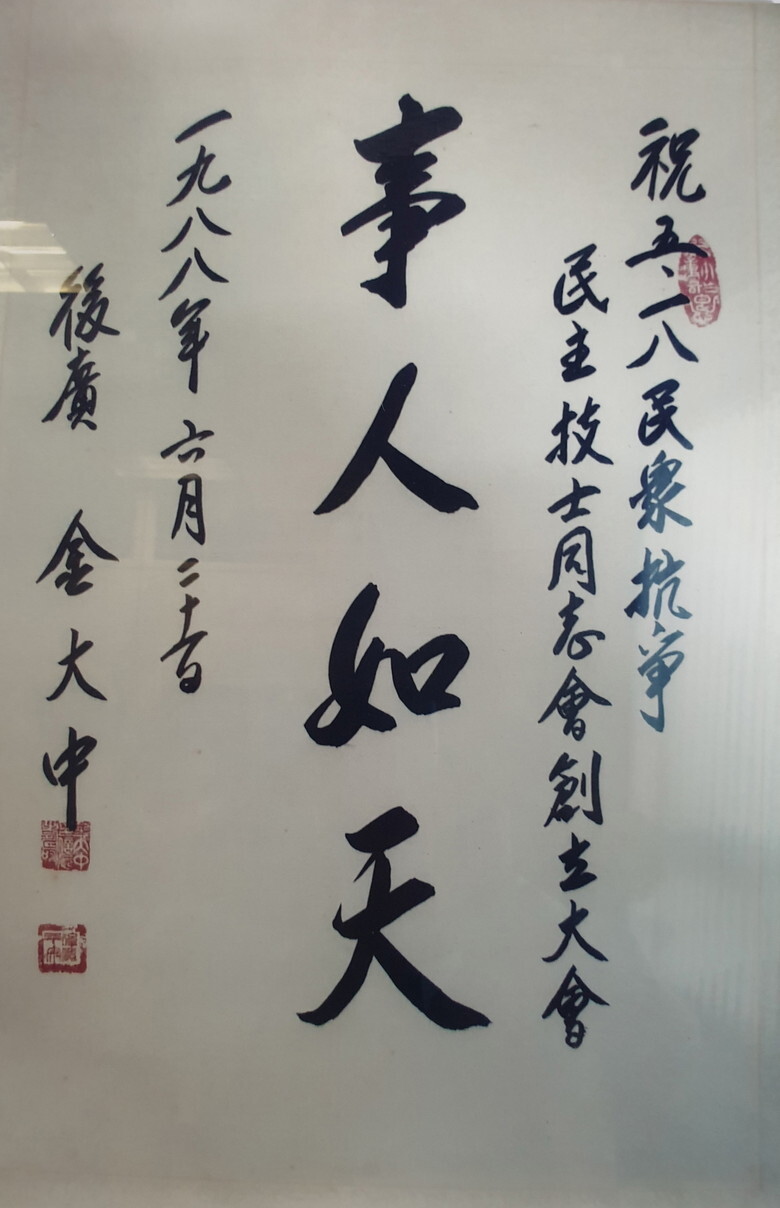

In 1986, the drivers who’d taken part in the protest started holding a reenactment on May 20 of each year and, in 1988, launched the Gwangju Uprising Association of Drivers for Democracy. Kim Dae-jung, who would later become South Korea’s president, even did a piece of calligraphy for the group. Lee started out as vice-chair and became chairperson the next year, a position he has held ever since.

Along with the Gwangju Democratization Movement Youth Association, the drivers’ association has stood in the vanguard of the campaign to restore the reputations of the massacre victims, to bring the guilty parties to justice, and to secure compensation. When Chun Doo-hwan, the president at the time of the Gwangju movement, stepped down in 1988 and went into “exile” at Baekdam Temple, the members of the drivers’ association took advantage of their mobility to drive to the temple in the hopes of seeing Chun.

That attempt was blocked by the police, but their feisty spirit is still alive today. When three members of the Liberty Korea Party (LKP, today called the United Future Party) made derogatory remarks about the Gwangju Democratization Movement last year, members of the drivers’ association made a point of attending protests held in front of the National Assembly, the LKP’s Gwangju office, and Chun’s home.

Dedicated to fighting historical distortions of movement

During the 40 years that have passed since the Gwangju Democratization Movement, the ranks of the drivers’ association have gradually thinned. At one point, the group had more than a hundred members, but now only 30 or so remain. In 1996, the association merged with the May 18 Arrested and Wounded Victims' Group and now calls itself the Democracy Drivers’ Committee. Group members take some consolation from the fact that the taxi drivers’ activities during the uprising were highlighted by the film “A Taxi Driver,” which had more than 10 million admissions upon its release in 2017.

Lee plans to stay focused on the campaign to correct the historical record about the movement. That will involve raising awareness about the vehicle protest that ignited the flames of the movement that May and confronting groups that attempt to disparage Gwangju.

“I’d like the South Korean public to recognize that uneducated workers such as ourselves fought against injustice. We want people to stop insulting us and bringing shame on us,” Lee said.

By Kim Yong-hee, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2After election rout, Yoon’s left with 3 choices for dealing with the opposition

- 3Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 4South Korea officially an aged society just 17 years after becoming aging society

- 51 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 8No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 9[Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- 10Why Korea shouldn’t welcome Japan’s newly beefed up defense cooperation with US