hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Column] The road that lies ahead for S. Korea

Delivering what may be the last National Assembly speech of his term on Monday, South Korean President Moon Jae-in said, “There have been a lot of darker aspects to [South Korea’s] high-speed growth to date.”

“Our low birth rate, our elderly poverty rate, our suicide rate, and our rate of deaths from industrial accidents are part of the Republic of Korea’s shameful self-portrait,” he said.

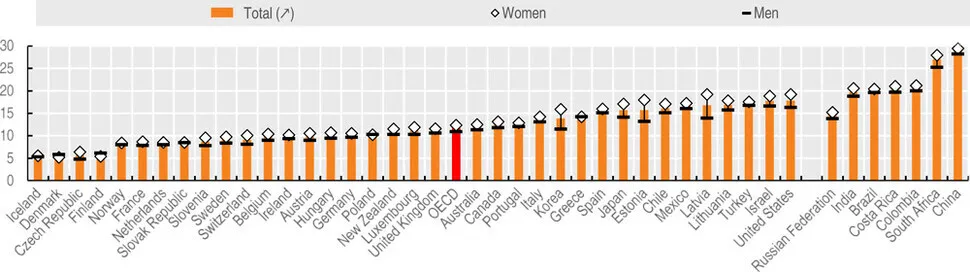

The depths of those shadows were in full view in an article published that morning, which noted that South Korea had the fourth-highest relative poverty rate among the 37 members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). According to a report by Yonhap News, South Korea had a relative poverty rate of 16.7% for the period 2018–2019, ranking it fourth in the OECD after Costa Rica (20.5%), the US (17.8%), and Israel (16.9%).

The relative poverty rate represents the portion of a country’s total population that earns less than 50% of the median income. This means that while people may have escaped absolute poverty, 16.7% of them — one-sixth of our neighbors — fail to enjoy the same standard of living that the majority of society does.

The various relative poverty rate charts listed on the OECD website provide a lot of food for thought.

South Korea’s poverty rate among people aged 65 and up was 43.4% as of 2018 — the highest percentage of any member country. This may be why Moon singled out the rate of poverty in old age in his speech to the National Assembly.

Poverty was not equally shared between women and men either. South Korea ranked among the top three countries for gender disparities in the relative poverty rate.

In most countries, the gender gap in relative poverty is not that large. It seemed somewhat bizarre, then, to see a graph showing South Korea listed apart alongside Latvia and Estonia as a place where the poverty rate is far higher among women.

To look at those graphs is to reflect on how we in South Korea have prided ourselves on becoming an “advanced country.”

While there has been some political debate, the success of our COVID-19 control measures — based on our outstanding social mobilization capabilities, the dedication of our healthcare professionals, and the willing cooperation of the public — showed the world how we possess advanced systems in a different sense from the countries of Europe and the US. And while it may not have succeeded completely, the Oct. 21 launch of the Nuri, a medium-sized satellite launch vehicle developed with domestic technology, did capture the world’s attention.

But behind the Billboard chart-topping successes of BTS, behind the rise of “Squid Game” to become the world’s most-watched TV series, behind all our crowing over Korean pop music, television, and beauty setting new global standards, the reality of South Korea today is one in which 1 in 6 of us languishes in relative deprivation, unable to enjoy the advantages of living in an “advanced country.”

Through the graphs, we can see that the South Korea of 2021 is also a place where young people work all night long to earn money for their tuition, and where many seniors set out in the early morning hours to collect waste cardboard for cash.

Being “advanced” does not mean that all the shadows disappear. The US had the OECD’s second-highest relative poverty rate, yet no one is going to tell you that it isn’t an “advanced economy.”

But in a day and age when the terms “world power” and “advanced economy” are easily confused, it’s vitally important that we consider and debate the direction in which our society should be heading. That’s a matter that turns our attention back to those OECD graphs to see the names of countries that rank low for relative poverty.

The Northern European nations that are frequently held up as model welfare states can be found at the very bottom of this graph, with low relative poverty rates. The figures for Iceland (4.9%), Denmark (6.1%), Finland (6.5%) and Norway (8.3%) are less than half that of Korea.

Problems of social inequality and polarization are difficult to resolve in a short period of time, and the gradual improvement in Korea’s relative poverty rate since 2011 is borne out in figures. However, it is also true that we have reached a point where it will be difficult to move forward without actively tackling rampant social problems such as poverty among older people and despair among young people.

It is also hard to deny that progressives, who believed that far better results would be achieved even without self-reflection on the part of the president, have failed to demonstrate a level of competence that lives up to the public’s expectations.

In the presidential election scheduled for March next year, I hope that candidates will address these issues head-on and seek to win votes by speaking clearly to the public about how they plan to resolve these social problems and redeploy the capabilities of the government and each sector of society in service of such goals. The ability to clearly convey this kind of message to the public is what we call vision.

While the countless suspicions and scandals raging online and swirling in the media in recent times are indeed far from trivial, from a long-term perspective they are nothing but brief whirlwinds passing by. What is more important is getting an accurate grasp of the light and dark sides of Korean society in 2021, and putting forward honest and concrete proposals to reduce the suffering found in those long, dark shadows.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Lee’s difficult task of striking a balance on Japan [Column] Lee’s difficult task of striking a balance on Japan](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/0905/6317570584144597.jpg) [Column] Lee’s difficult task of striking a balance on Japan

[Column] Lee’s difficult task of striking a balance on Japan![[Editorial] Multipolar era means Seoul must broaden its diplomacy [Editorial] Multipolar era means Seoul must broaden its diplomacy](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2025/0904/2017569747213826.jpg) [Editorial] Multipolar era means Seoul must broaden its diplomacy

[Editorial] Multipolar era means Seoul must broaden its diplomacy- [Column] North and South Korea are no longer pawns in US-China-Russia relations

- [Column] Who we fail when we oversimplify the ‘comfort women’ issue

- [Column] How Seoul can navigate its security in a shifting world order

- [Editorial] Former first lady’s indictment is consequence of her acting as though she were president

- [Correspondent’s column] A report card for the Lee-Ishiba summit

- [Editorial] America’s penchant for plundering allies

- [Editorial] Kim Jong-un’s return to diplomacy could be the start of a tectonic shift

- [Editorial] Lee clears first hurdle with Trump, but the race is not over yet

Most viewed articles

- 1Trump’s temperamental tariffs aren’t the win Americans think they are

- 2USFK sprayed defoliant from 1955 to 1995, new testimony suggests

- 3Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 4Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty

- 5“A bundle of blackened bones”: The search for unmarked graves of those killed in Gwangju Uprising

- 6[Editorial] Multipolar era means Seoul must broaden its diplomacy

- 7[Column] North and South Korea are no longer pawns in US-China-Russia relations

- 8Koreans are getting taller, but half of Korean men are now considered obese

- 9Records show how America stood back and watched as Gwangju was martyred for Korean democracy

- 1069% of Koreans use Galaxy phones, but majority of 20-somethings prefer iPhones