hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

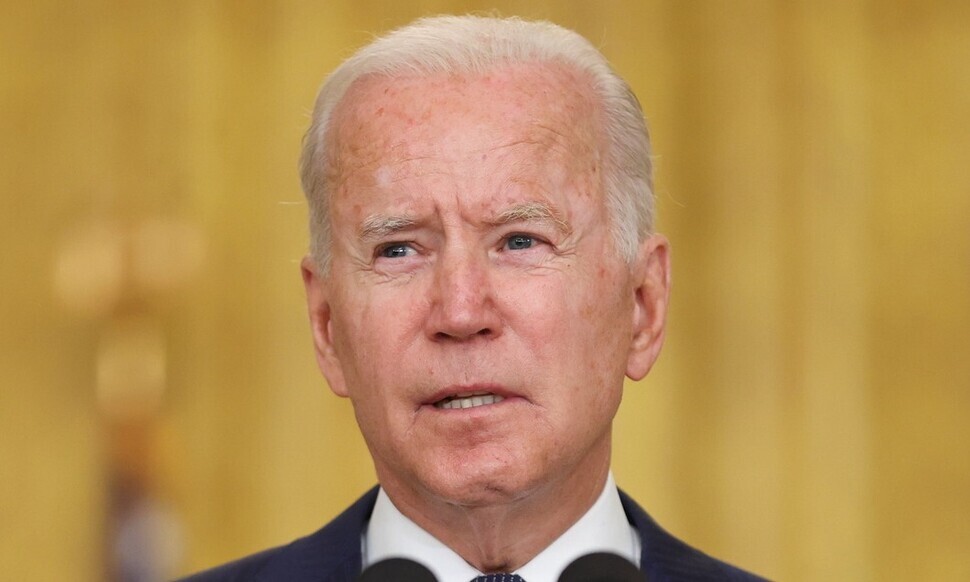

[Correspondent’s column] Biden and the window for S. Korean foreign policy

In the ten months since he took office, US President Joe Biden has been putting his foreign affairs principles into practice.

He has prioritized the values of democracy and human rights with the scheduled hosting of a Summit for Democracy and a possible diplomatic boycott of the Beijing Winter Olympics; worked to restore alliances from their state of disarray by improving relations with NATO, preserving the Quad, establishing AUKUS; and avoided involvement in wars that do not aid the national interest by withdrawing troops from Afghanistan.

A central axis in Biden’s foreign affairs approach has been the strategic rivalry between the US and China — a competition that could reasonably be called the foundation of the global order these days.

The US is in fierce competition with China in the areas of security, technology, trade, and human rights, while pursuing cooperation in areas such as the environment and public health. Contrary to fears that the two sides’ rivalry would spiral into a new Cold War, the US has so far been seeking out a form of coexistence within what Biden referred to as “guardrails” to prevent the competition from turning into a collision.

In the case of South Korea-US relations, cooperation has intensified considerably during the Biden administration in areas ranging from national security to the economy, technology, the environment, and public health. It’s a trend encapsulated in the joint statement from their summit in May, which bore the subheadings “The Alliance: Opening a New Chapter” and “The Way Forward: Comprehensive Partnership for a Better Future.”

Indeed, South Korea’s stature has risen rapidly in Washington, and the areas it has become involved in have diversified as well.

Last year, South Korea was touted as a model of COVID-19 response. It’s a key partner on semiconductor supply chain issues — which the US is approaching as a matter of national security — and one of five countries (alongside China, Japan, and the UK) that joined forces with the US to release strategic petroleum reserves in order to keep oil prices in check.

This is to say nothing of the considerable “soft power” it wields, as represented by the successes of BTS, the movie “Parasite” (2019) and the TV series “Squid Game.” According to an official at one Washington think tank, whereas Washington traditionally associated “Korea” with North Korea in the past because of the nuclear issue, these days a focus solely on that issue when talking about South Korea in Washington is likely to leave people empty-handed.

The change has been visible since the Biden administration took office, but it has been accelerated on the new foundations of the COVID-19 pandemic and the strategic rivalry between the US and China. Beyond security needs, Washington — along with the rest of the world — is gaining a new awareness of South Korea’s economic, social and cultural capabilities. Seoul, for its part, will need to focus its foreign affairs approach on taking maximum advantage of the window of opportunity the pandemic and US-China competition have opened.

This means it will have to move beyond the attitude that South Korea is sandwiched in between the US and China and being forced to take a side.

The US-China rivalry itself is such a complex mixture of conflict and cooperation in so many different areas that it is difficult to even determine who has come out ahead. In a talk with the Future Consensus Institute (Yeosijae) early this year, Council on Foreign Relations President Richard Haass pointed out that the US cannot ask other countries to break off relations with China when it has not fully severed its own ties with it.

For the foreseeable future, we are likely to see the same kind of hot-then-cold scenario play out, where the US and China announce the release of petroleum reserves side-by-side one moment, then the next moment China objects to the US inviting Taiwan to its Summit for Democracy.

In terms of the Korean Peninsula, the Biden administration has set the objective of achieving the peninsula’s complete denuclearization — adhering closely to a principle of cooperating closely with South Korea as it adopts a diplomatic and pragmatic approach toward the North. One clear difference is that there are none of the “surprise events” seen during predecessor Donald Trump’s administration.

There are also limits to how much rapid progress can be made in North Korea-US dialogue at a time when countries around the world are facing urgent domestic issues with worsening inequality and the negative economic impacts of the pandemic. This suggests the South Korean government will need to adjust its approach of devoting seemingly all its diplomatic capabilities to the North Korean nuclear issue.

Focusing diplomacy on the North Korean nuclear issue has its positive side in terms of fostering a climate of peace on the peninsula — but when it fails to produce results, it only breeds skepticism. As Washington’s “North Korea fatigue” wears off, the need to find a new approach to getting Pyongyang to take part in dialogue is looking more and more urgent.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 2‘We must say no’: Seoul defense chief on Korean, USFK involvement in hypothetical Taiwan crisis

- 3Is N. Korea threatening to test nukes in response to possible new US-led sanctions body?

- 4Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 5Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 6No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 7[Editorial] Korea’s surprise Q1 growth requires objective assessment, not blind fanfare

- 8Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 9N. Korean delegation’s trip to Iran shows how Pyongyang is leveraging ties with Moscow

- 10Amnesty notes ‘erosion’ of freedom of expression in Korea in annual human rights report