hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

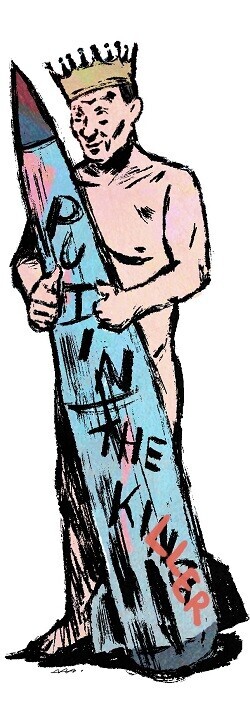

[Column] The war in Ukraine is a moment of truth

By Pak Noja (Vladimir Tikhonov), professor of Korean Studies at the University of Oslo

It’s a cliché, but war truly is hell. Wars of aggression, in particular, are utterly unjustifiable. Along these lines, it’s reasonable for us to declare our opposition to any aggressions, whether they are committed by the US or Russia.

But in addition to being a crime, war is also a moment of truth. When war breaks out, all the things concealed in the past beneath different forms of propaganda show their true face.

The US invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan clearly showed both the relative military dominance of the US and the decline of its overall hegemony. The US military succeeded in overcoming the resistance of the regular forces and occupying bases in both countries. But it failed to set up stable pro-US administrations in either of them, and it was ultimately forced to end its occupations.

Through those two wars, we learned that while the US may still be the world’s strongest military power, it can no longer exercise the same hegemony it did in the past in major regions such as the Middle East that fall outside of its core sphere of influence, which includes North America, Europe, Japan and South Korea.

So what has the war of aggression in Ukraine told us since it was launched over three weeks ago?

First, the Russian forces have not been as strong as predicted.

The situation might change if there’s a full mobilization, but the standing army — a mixture of conscripts and volunteers — has not been especially impressive. Unable to achieve a swift victory over a moderately sized army like Ukraine’s, which is the 22nd largest in the world, it has instead found itself drawn into a war of attrition.

Also, while there are no exact figures as yet, the general estimate among Western military experts is that the Russian death toll over the past three weeks has stood at around 5,000. That’s similar to the combined loss of life among US troops during America’s eight-year Iraq invasion.

This means that Russia’s military still follows the old-fashioned model of the mid-20th century: one that relies more on the sacrificing of soldiers than on technology. There are also many reports suggesting that morale among the troops is extremely low due to the very weak rationale for the war of aggression.

The key takeaway for us is that it may be extremely unlikely that Russia would attempt further territorial expansions with such a military.

It may end up that China — Russia’s main partner, which has been getting an indirect taste of the conflict — will find it more difficult to adopt a course of military adventurism, including a possible invasion of Taiwan, after seeing the bitter battle Russia has faced in its own invasion. Russia and China may have risen recently as rivals to the US, but they are still far behind it in terms of military strength.

Second, there is the question of how much Russia has actually achieved in its diplomatic war, having already shown so many weaknesses in military terms. While Russia’s military strength may not have lived up to expectations, the diplomatic response to its invasion has been less unified than one might have predicted.

In that regard, it’s worth considering the result of the March 2 UN General Assembly vote on a resolution condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Most of the countries backed the resolution, including the US and its allies, but major non-Western countries abstained, including China, India, Iran and South Africa. In other words, the major countries of Asia, Africa, and Central and South America — not including South Korea, Japan, and Singapore — opted to remain closer to neutral in the power battle between Russia and the West.

The reason Russia has been able to keep up its confrontations with the West in spite of the historically harsh Western sanctions against it is because of its continued expectation that it can circumvent them by means of countries such as China, India, Turkey, the United Arab Emirates, Israel, and the nations of South America.

Indeed, it seems quite significant that even US allies like Israel have declined to take part in the sanctions against Russia. What this war has shown us is that under a system of global capitalism that is becoming increasingly multipolar, US rivals like Russia and China can mount relatively stiff challenges to the US, even if they cannot match it militarily.

Third, Russia has suffered an utterly comprehensive defeat in its information warfare and public opinion campaigns.

This could be seen as a consequence of all the flattery and indulgence that powerful figures enjoy in dictatorial states. It looks as though intelligence agents plied the leadership and state leaders with the stories they were hoping to hear: that the Ukrainian military and civilians were angered with pro-Western policies and would greet the Russian forces as a “liberating army.”

As it turned out, the “analyses” and “reports” they drafted were little more than fiction. Instead, it was the Western intelligence institutions that showed far greater expertise in predicting the Russian invasion.

Like its intelligence capabilities, Russia’s war propaganda has proven incredibly shoddy.

It has spoken of “de-Nazifying” a country that elected a Jewish president with family members victimized during the Holocaust. It has made remarks denying the independent existence of a Ukrainian nation. It has even made claims that US experts have “set up a laboratory in Ukraine to develop special biological weapons that only target ethnic Russians.”

It’s the sort of story you might find in science fiction, and there was never any likelihood of it being taken seriously by open public opinion markets like those of the West or South Korea.

The reason Russia’s state propaganda organs have been indulging mostly in this kind of childish yarn-spinning is that their own domestic public opinion market is all but completely sealed off. Some highly educated members of Russia’s middle class will often read Western and foreign media online, but the 60 to 65 percent of Russians who have supported Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine have been exposed almost exclusively to Russian media.

We see the same situation with China’s state propaganda, which enjoys a massive captive market for information at home — a monopoly where competitors are unable to take part — but enjoys almost no credence in the West or Korea. It’s one of the key weaknesses of authoritarian countries.

Taken together, all of this seems to suggest that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine illustrates the state of affairs at a time when US hegemony is on the wane.

As the lesser of the two countries that have been the chief rivals of the US despite their military inferiority — China being the other — Russia now feels sufficiently emboldened by the relative weakening of US dominance to undertake a direct military invasion of a lower-level partner of the US and Europe. What makes this invasion economically possible, in spite of the negative global opinion and the sanctions imposed by the West, has been Russia’s anticipation that in a multipolar world, it can find new partners to take the place of the West.

At a time like this, the most urgent order of business for civil society around the world is not for us to take “sides” in battles for hegemony, but to offer our support and assistance to the Ukrainians who are courageously defending their homeland and the Russian activities who are putting their lives at risk to oppose war and end their dictatorship.

In the final analysis, the power to repel Putin’s invasion and end his dictatorship must come from the people of Ukraine and Russia.

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles![[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0430/9417144634983596.jpg) [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

[Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

Most viewed articles

- 1Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 2At heart of West’s handwringing over Chinese ‘overcapacity,’ a battle to lead key future industries

- 3[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- 4Trump asks why US would defend Korea, hints at hiking Seoul’s defense cost burden

- 5Fruitless Yoon-Lee summit inflames partisan tensions in Korea

- 6Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023

- 71 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 8[Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- 9First meeting between Yoon, Lee in 2 years ends without compromise or agreement

- 10Under conservative chief, Korea’s TRC brands teenage wartime massacre victims as traitors