hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[News analysis] The vaccine wars

“We plan to commit everything we have to becoming the first country in the world to develop a vaccine for the COVID-19 virus.”

These were the remarks of UK Health Secretary Matt Hancock as he announced on Apr. 17 that the University of Oxford was beginning clinical trials on a COVID-19 vaccine. It was an expression of commitment in the face of an unprecedented situation. On Apr. 23, Oxford began their first clinical trials. A total of 510 healthy adults aged 18 to 55 participating – they’re the largest scale of any clinical trials conducted to date. The UK is also the country that developed the world’s very first “jennerization” vaccine in the late 18th century. On Apr. 22, the German company BioNTech received clinical testing approval for four candidate vaccines.

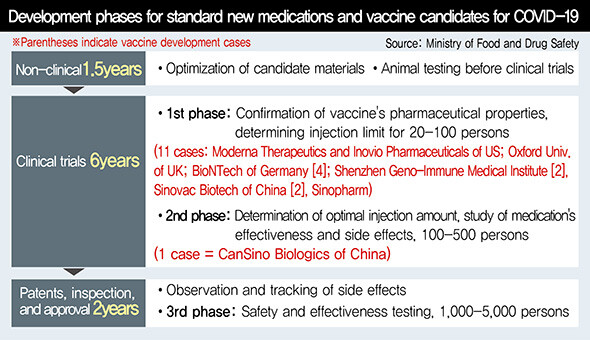

The race to develop a vaccine to the COVID-19 is heating up as the UK and Germany join the US and China in conducting clinical trials. The number of candidate vaccines used in the trials has already exceeded 10. It’s a battle for vaccine “dominance,” with different countries pledging to become the “world’s first.” Political factors also appear to be at play, including the UK’s role as the originators of vaccination, Germany’s pride as Europe’s leading power, China making up for its botched initial response to the virus, and the US awaiting a presidential election in November. China has been the most active among them, with clinical trials already under way for five candidate vaccines.

In the space of four months, the number of people diagnosed with the COVID-19 virus is approaching 3 million. Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) Director Jung Eun-kyeong has mentioned the possibility of “repeated cycles of the virus spreading and abating before turning into a major outbreak when the winter arrives with favorable conditions for the virus to appear.” The message underscores the need to prepare for a long-term fight. Under those circumstances, a vaccine represents a more fundamental response than treatments.

A vaccine is used to generate antibodies within a person’s body. Traditional vaccines have made use of actual viruses: a virus that has had its virulence reduced or eliminated is introduced into the body to produce an immune response without causing illness. It’s an effective approach, but it has a drawback in terms of how long the process takes. With the coronavirus situation becoming increasingly urgent, most vaccine development efforts have focused on genetic engineering, which allow for fast and simple development. The most recent approach is a nucleic acid vaccine, which involves introducing genetic material to create antigen proteins. Under this approach, genetic material is introduced to produce antigens, which are used to produce an immune response within cells.

Illustrative examples include the vaccines by Moderna Therapeutics and Inovio Pharmaceuticals that are currently undergoing clinical trials in the US. The Moderna vaccine uses RNA: messenger RNA containing a genetic code for the spike proteins on the virus’s surface are introduced to the body to produce “fake spike proteins” that induce the formation of antibodies. The spike proteins are used by the virus as a tool to infiltrate the body. Clinical trials -- the first anywhere in the world -- were launched in March. The Inovio vaccine, which began clinical testing in early April, is a DNA vaccine, which makes use of DNA plasmids (genetic material that creates antigen proteins).

An advantage of nucleic acid vaccines is their safety, as they do not employ the actual virus. They’re also easy to produce, since the virus does not need to be cultured. The problem is the lack of experience in using them on human beings -- which means that their safety and efficacy has not been tested. Adrian Hill, director of the Jenner Institute at the University of Oxford, likened the situation to having created a car but not yet knowing whether it can be driven.

10 S. Korean businesses and institutions developing vaccine; none of them have reached clinical trial stage

Three of the five candidate vaccines undergoing clinical trials in China also use genetic engineering methods. Under this approach, genes for specific coronavirus proteins are introduced into another virus that has had its virulence eliminated in order to produce an immune response. These are known as recombinant vector vaccines, as they involve recombining genes from other viruses for use as vectors. The vector used for a vaccine developed by China’s CanSino Biologics is an adenovirus, a pathogen responsible for the common cold. CanSino recently began the world’s first Phase 2 clinical trials -- just a month after launching Phase 1.

In South Korea, around 10 businesses and institutions have begun work on developing a vaccine, including the Korea Research Institute of Chemical Technology (KRICT). To date, none of them have reached the clinical trial stage, but the International Vaccine Institute and the Korea National Institute of Health have announced plans for domestic clinical trials with the Inovio vaccine in June.

The development of vaccines is generally understood to take upwards of 10 years. The fastest-developed vaccine ever -- for the Ebola virus -- took five years. There is a possibility a vaccine for COVID-19 could come sooner, with full-scale support being provided by governments, companies, and international organizations around the world. International organizations have offered funding, while governments have expedited approval procedures; companies are working to speed up the timeline by skipping over some testing phases or conducting multiple tests simultaneously.

Inovio currently plans to finish its clinical trials by the fall and create 1 million doses by the end of the year for emergency use. Moderna also plans to finish Phase 3 clinical testing within the year. CanSino aims to complete its clinical testing by this fall. The World Health Organization (WHO) has predicted that while there may be some difficulties, a commercialized vaccine could arrive within 12 to 18 months. Given the 10 minutes taken between Phase 1 and Phase 3 clinical trials for the Ebola vaccine, the target is not out of the question.

Of course, all of this assumes that the development and testing will proceed smoothly. Speaking at a KAIST international forum on Apr. 22, International Vaccine Institute Director General Jerome Kim said, “About 7% of candidate vaccines proceed to the animal testing and clinical trial stages, and then it’s a question of whether one in 10 will succeed.” Based on the rate of the current development process, it appears likely to become clearer by the summer which vaccines might actually be used for inoculations.

Concerns about rapid vaccine developmentAt the same time, many are voicing concerns that the process may be going too fast. The fear is that if corners are cut in safety testing, a vaccine could end up turning into a deadly toxin itself. Thalidomide, a morning sickness medication developed in the 1950s, ended up causing deformities in over 10,000 people -- the result of too much trust being placed in animal test results, while clinical trials were neglected. During an online forum titled “How far have we come with COVID-19 treatment and vaccine development?” held on Apr. 17 by the Korean Federation of Science and Technology Societies (KOFST) in conjunction with the National Academy of Medicine in Korea (NAMOK) and the Korean Academy of Science and Technology (KAST), experts stressed that more emphasis needs to be placed on safety.

“In the case of COVID-19, there’s an urgent need for a vaccine, but it could create an even greater danger if [development] takes place without scientific design and evaluation,” said Park Hye-sook, a professor in the preventive medicine department of the Ewha Womans University College of Medicine.

“The vaccine review process needs to be centered on safety, not societal pressures,” she stressed.

Another major hurdle arises once a vaccine has been successfully developed: the question of how to address the imbalance in supply and demand. Meeting the demand for a coronavirus vaccine would require billions of doses. Production capabilities are unlikely to keep up with demand for some time -- and supply-demand imbalances have the potential to breed conflict. To achieve the maximum effect with limited quantities, the optimal approach would be to supply the vaccine to high-risk groups. But a country that manufactures the vaccine is going to want to provide to its own public first. This could lead to a situation of greater damages for the world as a whole.

Uncertainty over which vaccine will succeed similar to “prisoner’s dilemma”In an interview with the British weekly The Economist, Richard Hatchett, CEO of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), explained that the world was facing the “prisoner’s dilemma.” The term refers to a situation in which two suspects in a crime are forced to make a difficult decision. Both will receive lighter sentences if they exercise their right to remain silent. But if one betrays the other, one is freed while the other is punished. According to Hatchett, the uncertainty over which vaccine is actually likely to succeed is similar to the one facing the two prisoners -- which means that it’s a moment where it remains possible to elicit global cooperation.

“As we become more and more certain about which vaccines are going to win, that advantage may go away and national interest may begin to assert [itself],” Hatchett predicted. According to this analysis, the question of whether humanity can escape the coronavirus quagmire hinges on the extent to which countries can free themselves from political considerations.

By Kwak No-pil, senior staff writer

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war![[Column] The state is back — but is it in business? [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0506/8217149564092725.jpg) [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

Most viewed articles

- 1[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 260% of young Koreans see no need to have kids after marriage

- 3Yoon’s broken-compass diplomacy is steering Korea into serving US, Japanese interests

- 4After 2 years in office, Yoon’s promises of fairness, common sense ring hollow

- 5[Column] Why Korea’s hard right is fated to lose

- 6S. Korean first lady likely to face questioning by prosecutors over Dior handbag scandal

- 7Is Japan about to snatch control of Line messenger from Korea’s Naver?

- 8[Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- 946% of cases of violence against women in Korea perpetrated by intimate partner, study finds

- 10[Column] The first year of war in Ukraine