hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

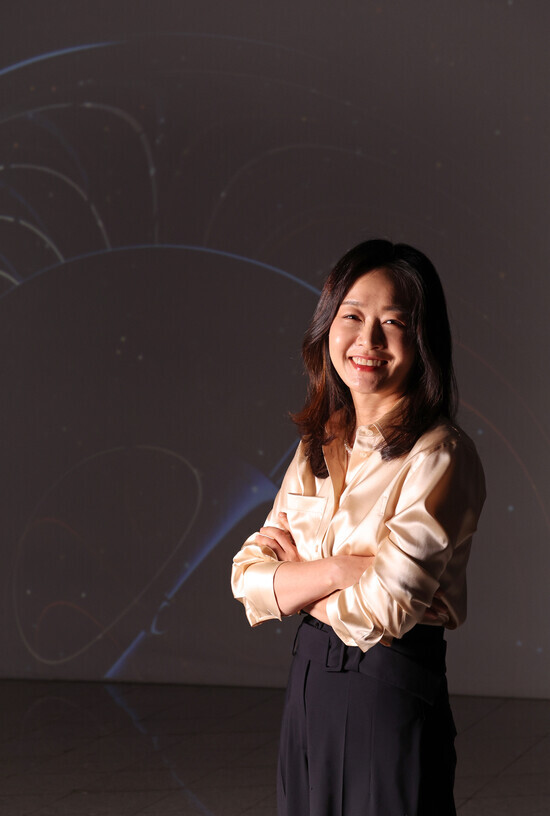

[Interview] For NCSOFT’s Yoon Songyee, fighting prejudice is about so much more than AI

When she stepped into the room, she realized she was the only girl there. It was 1985 and Yoon Songyee, a fourth grader at the time, was at a Sciencebox assembly contest. “Figures,” she thought as she looked around.

Following her days at KAIST, where she went to student retreats with her peers at women’s colleges, and after receiving her PhD from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in the US at age 24, Yoon joined McKinsey & Company and went into a conference room for a consultation, only to be met by 300 male executives from her client company.

20 years later, Yoon, 47, is now the chief strategy officer at NCSOFT. From AI girl genius to one of the most well-known women in business in South Korea, Yoon’s transformation begs the question: What’s next?

“ChatGPT, which has stirred an artificial intelligence (AI) craze, provides responses full of implicit bias. This is because the data set the AI was trained with is chock-full of human bias.”

On Friday, Yoon made the above statement while giving the keynote address for the second Hankyoreh Human and Digital Forum, held at the Korea Chamber of Commerce and Industry building located in the Jung District of Seoul. At the event, which was centered around the topic, “Conditions for Coexistence between Human and AI in the Age of ChatGPT,” Yoon was the only woman participating as a presenter.

The Hankyoreh sat down with Yoon for a one-on-one interview. An AI aficionado and researcher at KAIST since her teens, Yoon harbored a philosophy on AI that intimately tied into her life story. Having received her doctoral degree from MIT at 24 and become the youngest executive in SK Telecom’s history at 28, which prompted her rise to fame, she’s barely given any media interviews focusing on herself since marrying NCSOFTfounder Kim Taekjin in 2008. The Hankyoreh asked her about the path she is on as well as the path of AI.

Our interview took place at the NCSOFT R&D center in Pangyo, Gyeonggi Province, on the morning of June 14.

The first floor of the building is home to Laughing Peanut, the 200-child daycare center that was built in 2013 under Yoon’s personal direction. Thanks to Laughing Peanut, one hears the babble of children heading to daycare when they step into the building — not exactly what one expects from the R&D building of a video game developer, where many of the researchers are men.

The interview lasted for three hours in a conference room on the 11th floor of the building.

“Biased data could push the diversity debate 30 years into the past”

Hankyoreh: Back in 2004, when you were being feted as a “girl prodigy” and one of the youngest board members at a major corporation, you were named one of the “50 women to watch in business” by the Wall Street Journal. You were also named a future mover and shaker on several occasions. Since then, you’ve had two children. Has taking care of them made it hard to maintain your previous level of work? What’s the latest in your life?

Yoon Songyee: Well, I’m not a prodigy, and I’m certainly not a young girl anymore either. [Laugh.] But my lifestyle is much the same. I devote the most energy to my management responsibilities as chief strategy officer of NCSOFT, president of our US branch NC West, and chair of the NCSOFT Culture Foundation. I’ve been on the board of trustees at MIT, my alma mater, for eight years now, and I’m also on the advisory council for the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence at Stanford University and on the board of trustees of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Hankyoreh: Since it’s a bit of an unfamiliar concept for many, could you explain what exactly a “chief strategy officer” like yourself does?

Yoon: My job is deciding what NCSOFT should and shouldn’t do. To take one example, there were a lot of questions about why a video game company hadn’t adopted blockchain. The fact is that after considerable research, we decided the technology is still premature. But we did move quickly to set up an AI department. To make responsible decisions, it’s important to be informed about both the market situation and trends in technology.

Hankyoreh: You’re staying in the US as the president of NC West, your company’s US branch. Considering that you’re an expert in AI, how did it feel to watch the birth of ChatGPT?

Yoon: It’s been quite interesting. What I’ve heard from people at OpenAI and Microsoft is that they didn’t expect ChatGPT to be such a hit when it came out last November. They opened it to the public to collect data needed for development, but ChatGPT is getting so much use that they seem to have realized it’s already a product.

Hankyoreh: In your address at the forum, you warned about AI bias. Can you elaborate on that a little?

Yoon: Just 10 years ago, a Google image search for the word “CEO” would give you rows and rows of white men, and nobody else. As I remember, the first woman in the search results was a Barbie doll. The search gave you those results because a lot of companies are indeed run by men, and white men in particular, in the world we live in.

Artificial intelligence is trained with data. If that’s the kind of data we feed AI, what else is it supposed to think about how CEOs look? What will people take away from that AI’s output, and how will they be affected? If it were up to AI, it’s pretty obvious what kind of people would get a chance to become CEO.

Hankyoreh: Are you saying that training AI on prejudiced data could foster more prejudice?

Yoon: A few years ago, the US company Amazon was already trying to use AI in hiring by getting it to learn from existing personnel data, and it ended up confirming this very problem of bias. They fed it data on the people at Amazon who had earned good assessments and earned promotions, and the results were more beneficial for the males who had been at an advantage in promotions, and more disadvantageous to females.

The glass ceiling ended up being reinforced, and the bias was so strong that Amazon decided not to use the technology in question.

Hani: What happens when prejudices are shaped by AI?

Yoon:You can end up with something where the values many people have been fighting for decades to achieve are instantly reversed. When AI has the result of just continually giving opportunities to men, that reinforces the preconception of “it looks like men just do better,” and women are given fewer opportunities.

The danger is that it can set our discussions on social diversity and equality of opportunity back 30 years. It’s similar to the principle of compound interest. It may be a tiny difference right now, but as those skewed advantages accumulate, it creates insurmountably large differences.

Hani: How can this be stopped?

Yoon:You have to teach it human aspirations rather than human preconceptions. In the case of autonomous vehicles, they needed to have them actually operating on the roads to acquire data about those roads. In their learning now, they’re making more proactive use of artificially generated 3D information based on simulated worlds they’ve created.

The same is true for AI: where there are prejudices in existing data, it needs to be able to correct them. So we can supplement the learning by creating synthetic data that shows the world the way we want it.

To do that, we need to be more responsible in terms of thinking about what it is our society is aspiring toward. It’s crucial for it to reflect our consensus and orientation as a society, not as individuals. We also need broader awareness and understanding of the potential for bias issues in these devices’ outputs.

Hani: It can’t be easy getting everyone to grasp that.

Yoon: Not long ago, I was floored when a professor asked me, “So do you want AI to be better than a person?” It’s not a question of whether AI should be “better” than people — it’s that it’s more dangerous when AI learns prejudices.

Last November, Yoon published “The Most Humane Future” based on her interviews with scholars at the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence. In the introduction, she mentions a time when she asked her employees why they didn’t have the same gender ratios for the hero characters in their games.

“Why?” came the reply — something she found unimaginable. At that moment, she came to realize that the way to find real answers is by constantly asking questions about the things we take for granted. It is the task that falls on human beings “to create a better future instead of repeating past mistakes.”

The real-life model of Lee Na-young’s character in “KAIST”

Hankyoreh: What made you interested in researching artificial intelligence?

Yoon:It was completely by chance. KAIST students need to decide on their major by their sophomore year, and the advisor I had in my freshman year was Kim Jin-hyung, a professor who many consider the godfather of AI research in Korea.

At the time, he was doing research to make computers recognize human handwriting, which is an early model of artificial intelligence. I went down the same path as him as I helped him out.

The 1990s was an AI winter, so many people said that there was no point in doing research on AI. So even if people were conducting AI-related research, people didn’t categorize it as such. They called it algorithms, robotics, or computer vision. In my junior year I started preparing for robot soccer competitions, and after I won awards I completely immersed myself in research.

Hankyoreh: Is it true that Lee Na-young’s character in KAIST was probably created based on that time of your life?

Yoon: I didn’t watch the TV series myself, but when I heard that there was an episode where Lee Na-young dropped her plate after reaching a research-related epiphany, I knew that was based on my own experience.

I only managed to meet the screenwriter, Song Ji-na, quite recently and she told me that when she was writing the script and interviewing students at KAIST, they all talked about a particular student.

She didn’t plan on making a character based on an actual person, but since she kept coming across these odd stories, she ended up making that character.

Hankyoreh: What sort of student were you?

Yoon: I was absorbed in my research. Training Unix computers is very time-consuming, so when you train them to do things, the whole process would end at around 3 in the morning. I couldn’t wait until the morning to see the results of the experiments, so I’d leave my dorm at 3 am and head to the lab.

I’d leave the lab at around 5 am, bleary-eyed and groggy, and mix in with crowds of people who’d just come back to their dorms after a night out.

Hankyoreh: Did many people think you were peculiar?

Yoon: The words that were used the most to describe me were “peculiar” and “different.” When I was only in third or fourth grade, I would go shopping for beakers, flasks and tripods. I remember going with my mom to a factory to buy hydrochloric acid.

I filled my bookshelves and cubbies with equipment and conducted experiments. I loved the science lab, so my teacher even let me borrow a microscope. I remember falling over one day and getting a bloody knee, then looking at the scrape under the microscope.

Hankyoreh: Were you only interested in science as a child?

Yoon: I liked reading and writing, so I would always copy down newspaper editorials in the morning. I also won a children’s writing competition that was held by a newspaper. When a bookselling vendor came to our neighborhood, I would nag my mother into buying a complete set of world classics, which I would read overnight. Then, I’d move on to reading the encyclopedia.

I listened to the English CDs that were attached to books over and over again. I also loved drawing to the point that I dreamed of going to art school.

Hankyoreh: So why did you choose science?

Yoon: In fifth grade, I went to a science exhibition at the Seoul Science Center and gave a presentation about an experiment that I did. One of the adults who listened to my presentation talked to me afterward. “You’re interested in science, I see. Right now, science high schools only allow boys to enter, but by the time you’re old enough, they’ll accept girls too. Make sure to go to one of those schools.” (Two years later, in 1988, Gyeonggi Science High School for the Gifted began admitting girls, and Seoul Science High School was founded in the same year.)

I matriculated at Seoul Science High School in its third year, graduated early, and went to KAIST.

Hankyoreh: What motivated you to go straight to the US after graduating early from KAIST?

Yoon: While studying, I realized that to be an engineer who creates technology for the good of people, you need to have a good understanding of people. I went straight to the National Library to read books about universities in the US and found out what department I should go to in order to learn about people.

I learned about MIT’s Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences and sent a US$70 check in the mail to apply.

Hankyoreh: What was it like earning your Ph.D. from MIT at 24?

Yoon: At the lab I was working in, I dealt with the “intelligence” part of “artificial intelligence.” I conducted research with a friend who was a filmmaker and a friend who later went on to do great work in graphics, and others. It was a fun time.

An ENTJ working mom, balancing the burden of housework for women

Hankyoreh: Working in engineering, you’ve probably had your share of experiences in androcentric spaces.

Yoon: I was in elementary school in the 1980s, so whenever I walked into the room for a Sciencebox building competition, oftentimes I would be the only girl there. It was the same when I went to math competitions, too.

Sometimes there were no women’s restrooms. Even in the electronics department at KAIST, there were only 7 women out of 220 students. There I was told, “We’re going to a college retreat with girls from the women’s university, so you keep quiet and do the dishes.”

·

In her book, “The Story of Laughing Peanut,” which describes the process of how Yoon organized the NCSOFT daycare center, she writes, “The fierce corporate life already demands us to be the best version of ourselves that we can be. When you add children to that burden, you have to plan and live as if you’re in charge of at least one or two more people, so working mothers often feel like they’re standing alone with sandbags on their legs in a 100-meter race where they have to run at full speed.” What did the race that she had to run after having children mean to her?

·

Hankyoreh: I’m sure that having children in 2009 and 2011 must have made you think about your career.

Yoon: My Ph.D. thesis was on “affective synthetic characters,” which is actually a perfect fit for the gaming industry. In the case of robot soccer, which I was obsessed with at KAIST, I had to face a rut whenever the hardware for the robot went bust.

You can do a lot more if you add intelligence to three-dimensional images instead of hardware. When I became a non-executive director of NCSOFT in 2004 after serving as an executive at SK Telecom, I realized that this company was doing everything I wanted to do: games, art, and business. It was natural for me to join the company after I got married.

Hankyoreh: It does look like AI and gaming go hand-in-hand with each other.

Yoon: Games are at the forefront of innovation. The gaming world has early adopters who are ready to embrace new things, and, unlike autonomous driving, there are fewer real-world risks, so games can be the first to experiment with AI. We have so much left to show the world.

In 2011, NCSOFT established an AI research organization, which has since grown to more than 300 professional R&D staff. Recently, the company made a “Digital Human” based on the company CEO, Kim Taekjin, which was unveiled by Yoon herself. The company is also taking the lead in establishing AI ethics with the name “[NC] AI Ethics Framework.”

Hankyoreh: Was it a natural flow of events for you to personally head to the US and set up the American branch?

Yoon: Going to America wasn’t originally in the plan. At the time, there were recurring issues with a key studio in Seattle. The problem came down to cultural differences between the local workers and the ones sent from headquarters. I raced over to the US to sort things out because it was at a point where some key people were on the verge of quitting.

In 2012, my eldest was 4, and my second child was 2. With the rush to go [to the US], it was hard to find a daycare, so I ended up sending them to a place that was a bit far from work. But they told me that because they weren’t licensed, they couldn’t change diapers. Each time one of my kids pooped, their teacher called me. My life involved a lot of running out of meetings to go change dirty diapers.

Hankyoreh: It can’t be easy to have to juggle a career and your role as a mother.

Yoon: The division of unpaid domestic work is the most pressing of problems when you look at Korea’s gender equality index. The proportion of unpaid domestic work shouldered by men in Korea comes to a mere 5%. That means the other 95% is being carried out by women who are also working for a wage elsewhere. Because women are a minority when it comes to status in Korea, we have to do double or triple the work for people to think we’re on the same level as men. It’s a serious problem.

“I love my dishwasher”

Hankyoreh: How do you parent your kids?

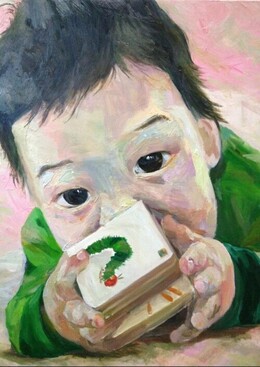

Yoon: My kids are pretty independent. By studying about people for the sake of AI, I ended up learning about brain development in children. There are certain periods in which they need to be stimulated. So I tried not to buy them toys, but instead have them play with their surroundings. One day, I told my youngest that I was playing a game that I made. Then, he started teaching himself how to make games. The graphics are pretty impressive. Now my oldest is starting high school and he’s interested in the environment, so he’s published a picture book about the environment.

Hankyoreh: You’re known to be very systematic with your time. How do you do it?

Yoon: I have a separate “housekeeping” calendar on my Google Calendar. That’s where I keep track of everything from my two boys’ schedules to gardening, pest control, wiping down solar panels, washing blankets, and sanitizing the dishwasher. I love gadgets that save time for me like my dishwasher, oven, and washing machine.

Hankyoreh: That’s pretty intense. Do you mind sharing your MBTI?

Yoon: I’m an ENTJ. My “N” (direct, future-oriented, possibility-searching, quick-working) is particularly strong.

Hankyoreh: What’s next for Yoon Songyee?

Yoon: I want to have fun with work, and there’s still a lot of fun out there to be had in the world. I’ll keep my nose to the grindstone.

·

In her book “The Most Humane Future,” Yoon writes, “The more chaotic and anxious the times, I think the clearer what humans are truly capable of becomes.”

“When facing a future in which nothing is decided, humans have always felt their way together, asking more and more as they search for where to place their next step, carrying their weak fates,” she writes, calling this “the most human way, the way only humans are capable of.”

In this way, Yoon looks poised to take her next diligent steps into to her most Yoon Songyee of futures.

By Lim Ji-sun, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0509/221715238827911.jpg) [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- 2Nuclear South Korea? The hidden implication of hints at US troop withdrawal

- 3Behind-the-times gender change regulations leave trans Koreans in the lurch

- 4‘Free Palestine!’: Anti-war protest wave comes to Korean campuses

- 5[Photo] ‘End the genocide in Gaza’: Students in Korea join global anti-war protest wave

- 6In Yoon’s Korea, a government ‘of, by and for prosecutors,’ says civic group

- 7Korean president’s jailed mother-in-law approved for parole

- 8[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

- 9AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 10Dermatology, plastic surgery drove record medical tourism to Korea in 2023