hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

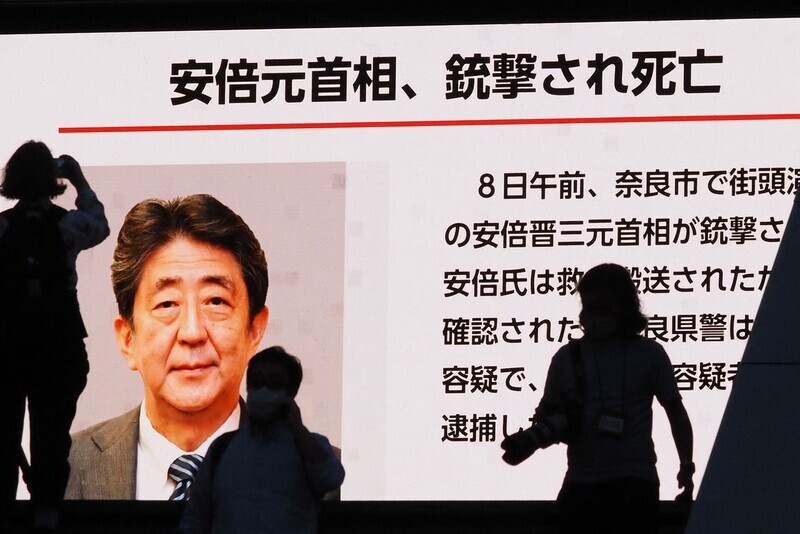

Shinzo Abe, prime minister who dreamed of a war-ready Japan, dead at 67

Former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was fatally shot during a streetside campaign rally on Friday, July 8. He was 67 years old.

Abe occupied the premiership for eight years and eight months, during two separate stints, longer than any other prime minister in Japan’s constitutional history. While in office, he spearheaded a rightward shift in Japanese politics.

Born in Tokyo in 1954, Abe entered politics in 1982 as the secretary of his father Shintaro Abe (1942–1991), who served as Japan’s foreign minister.

In 1993, two years after his father’s death in 1991, Abe was elected to Japan’s House of Representatives for the first time, claiming his father’s old seat.

Abe, who was one of Japan’s “hereditary politicians,” came to the notice of the country’s right wing after staking out a hard-line position on the so-called “comfort women,” which was becoming a major issue at the time.

The decisive factor behind Abe’s rapid rise in politics was the first visit to North Korea by then-Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi in September 2002. Abe accompanied Koizumi on the trip as his deputy chief Cabinet secretary.

Later, Abe began building his reputation as a “reliable right-wing politician” by calling for decisive action on the issue of North Korea’s abduction of Japanese citizens.

In recognition of Abe’s growing clout, Koizumi named him secretary general of the Liberal Democratic Party in 2003 and then chief Cabinet secretary, considered the No. 2 position in the Cabinet, in 2005.

After stints in all the major positions in the party and the Cabinet, Abe rose to the premiership in 2006, at the age of 52, making him Japan’s youngest prime minister. He was also the first prime minister from the postwar generation.

During his first term in office, Abe spoke of “leaving behind the postwar system” as a catchphrase. Concluding that the Japanese Constitution barring the country from possessing a military and waging war had been enacted under occupation by Allied powers in the wake of Japan’s World War II defeat, he declared plans to overcome that situation by amending the text.

A key influence on Abe’s attitude was his maternal grandfather, former Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi (1896–1987), who was also a suspected Class A war criminal.

Kishi also viewed Japan’s pacifist constitution barring the possession of a military as something that the US had forced upon it. He too attempted to amend it but failed. Abe carried on that aim, remaining unbending to the end in regarding the amendment of Japan’s Constitution as his “life’s work.”

Abe’s first term did not last long, ending after a year. He focused his energies on conservative, ideological policies such as amending Japan’s Fundamental Law of Education, and on attacking the Kono Statement of 1993, which acknowledged the forcible nature of the mobilization of “comfort women.” He also struggled with gaffes and political scandals involving his Cabinet members.

In late July 2007, the US House of Representatives responded with a resolution on the comfort women issue, and the LDP also met with a rout in a House of Councillors election held around the same time. This, together with the worsening of his ulcerative colitis, led him to announce his resignation on Sept. 12, 2007.

At the time, critics denounced him for giving up his administration too easily. A comeback appeared unlikely.

But Abe was plotting his return. He succeeded in being elected for a second time in December 2012, campaigning with an emphasis on pragmatic policies such as “Abenomics,” along with a muscular diplomatic approach to China’s threat to the Senkaku (Diaoyu) Islands.

His orientation was still conservative, but he adopted a somewhat moderated approach to his administration. Instead of emphasizing ideology, he started off his return to office with an “Abenomics” approach that involved monetary easing. His focus was on economic policies with bearing on the real lives of the Japanese public.

This clever approach proved effective, and Abe’s second term in office stretched for a long seven years and eight months. That period saw a July 2014 alteration of a constitutional interpretation to permit the exercising of “collective self-defense,” along with the enactment and amendment of security legislation to specify this in September 2015.

In 2016, Abe began speaking about his vision for a “free and open Indo-Pacific.” That concept would end up adopted as the current US strategy on East Asia — taking concrete shape with the creation of the “Quad” framework. Responding to the two issues of China’s rise and the US’ relative decline, this approach involved transforming the US-Japan alliance into a “global alliance” with a greater scope of activities and roles than before.

Through his second period in office, amending the pacifist constitution remained Abe’s objective.

In May 2017, he announced plans for an amendment that would include provisions regarding the Japan Self-Defense Forces, while leaving in place Article 9, which renounces Japan’s right to belligerency. He even named a target date of 2020. Given the victories that the LDP had enjoyed in all Diet elections since he took office for the second time, the achievement of his “life’s work” appeared to be in his grasp.

But it ended up not coming to pass, as the opposition dug in its heels and the Komeito, a party forming a coalition with the LDP, signaled its skepticism.

As Abe’s administration continued in the long term, the public’s fatigue also increased. He suffered political blows with scandals involving the private school operator Moritomo Gakuen — where a corporation operated by people close to or apparently close to him were alleged to have received preferential treatment — and a so-called “cherry blossom party” that allegedly used state funds to entertain supporters.

The final contributing factor to Abe’s decision to step down from his post as prime minister came with the COVID-19 pandemic. The Summer Olympics in Tokyo ended up having to be postponed a year, while the Cabinet’s approval rating dipped below 30%, putting it in what was referred to as the “danger zone.” In August of that year, he announced his intent to resign due to a recurrence of his ulcerative colitis; the following September, he abruptly resigned.

Even after he stepped down, he continued to wield huge power over the Japanese political world from behind the scenes. His successor as prime minister, Yoshihide Suga, described it as his “mission to carry on the policies pursued by Prime Minister Abe.”

Fumio Kishida, who took office as prime minister in October 2021, was in no position to ignore Abe’s influence either. The former prime minister remained the head of the LDP’s largest single wing, known as the Seiwa Policy Research Council.

Abe’s death evokes conflicted responses in South Koreans. He was a historical revisionist who declared that Japan would no longer apologize or show remorse for its colonial activities in the past, and he was a right-winger who sought to amend the pacifist constitution and give Japan the power to wage war once again.

In December 2015, he declared the issue of Japanese military sexual slavery to have been “finally and irreversibly resolved” through an intergovernmental agreement with South Korea. With that agreement, he sought to establish a trilateral alliance consisting of South Korea, the US, and Japan.

In October 2016, Abe faced demands for him to send a letter of apology to sexual slavery survivors. He rebuffed the request, saying he had “not a shred” of intention to do so.

What Abe wanted was for South Korea and Japan to forget the past and cooperate on security matters. His legacy now appears poised to continue in Japanese politics for a long time to come.

By Cho Ki-weon, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0426/3317141030699447.jpg) [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon![[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0424/651713945113788.jpg) [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

- [Column] The president’s questionable capacity for dialogue

- [Column] Are chaebol firms just pizza pies for families to divvy up as they please?

- [Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- [Correspondent’s column] In Japan’s alliance with US, echoes of its past alliances with UK

Most viewed articles

- 1AI is catching up with humans at a ‘shocking’ rate

- 2Korea’s 1.3% growth in Q1 signals ‘textbook’ return to growth, says government

- 3[Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- 4[Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- 5No good, very bad game for Korea puts it out of Olympics for first time since 1988

- 6Marriages nosedived 40% over last 10 years in Korea, a factor in low birth rate

- 7Division commander ordered troops to enter raging flood waters before Marine died, survivor says

- 81 in 5 unwed Korean women want child-free life, study shows

- 9[Column] Has Korea, too, crossed the Rubicon on China?

- 10Will NewJeans end up collateral damage in internal feud at K-pop juggernaut Hybe?