hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

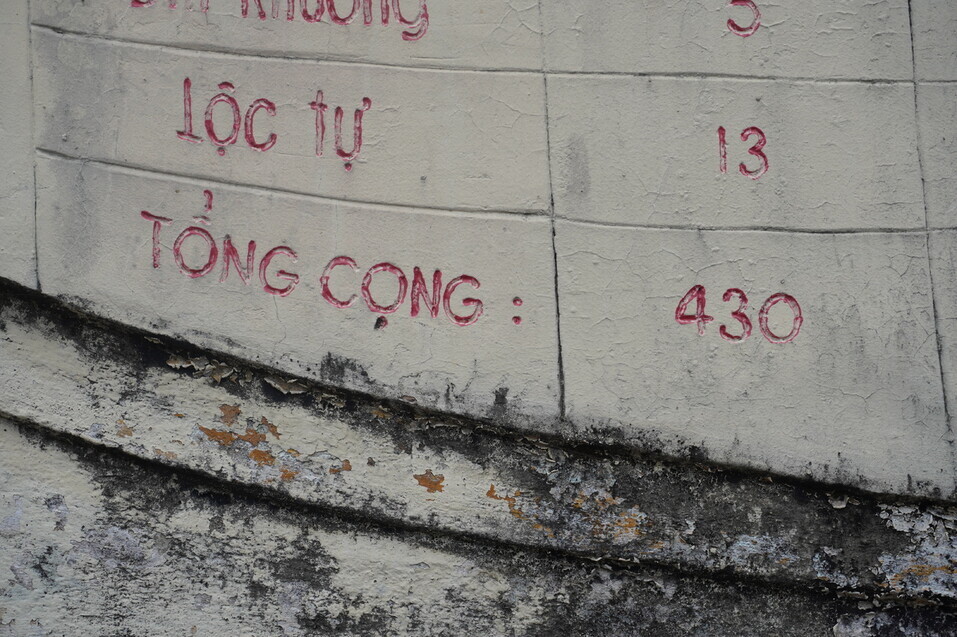

Monument of hate stands as record of 430 Vietnamese villagers slaughtered by Korean troops

“Their savage and bloodthirsty nature drove them to open fire as soon as they set foot on this small country, slaughtering thousands of innocent civilians. . .”

The “monument of hate” (bia căm thù), that the Hankyoreh visited on Sept. 3 at the entrance of the Bình Hoà commune in Quảng Ngãi, a coastal province in central Vietnam, was in the shape of a giant open book.

It looked as if it hadn’t been maintained since being repainted in 2010, with dark grim smeared all over it. The long, vertical streaks of grime almost looked like tears that had run down the monument.

Between all the words in a foreign alphabet, the number “430” came into focus at a closer glance. The story the monument tells in silence is as follows:

“In December 1966, 430 villagers were killed. Dec. 3 - Dec. 6. It took only four days for them all to die. Of the deceased, 268 were unarmed women. Seven were pregnant, and two were killed after being raped. 108 children were also killed. In some cases, entire families were wiped out. The gunmen were South Korean soldiers who landed in Vietnam in October 1965.”

Fifty-nine years ago, on Sept. 11, 1964, Korea sent 140 soldiers belonging to the medical corps to Vietnam as part of the war effort. Over the nine years that followed, South Korea would end up sending a total of 346,393 troops to fight in Vietnam in its Blue Dragon, Fierce Tiger, and White Horse divisions. Their mission was to help the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam) fight the Democratic People’s Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) and the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam (Viet Cong). The enemies in this fight were clearly defined.

But often, the muzzles of Korean soldiers’ guns were pointed at civilians. In the entire province of Quảng Ngãi, more than 1,700 civilians were killed by Korean troops. In the Bình Sơn district’s Bình Hoà commune alone, 430 people were massacred, making it the largest number of civilian massacres in a single district. Survivors of the massacre say the soldiers wore patches with blue-colored dragons — the insignia of the 2nd Marine Infantry Division — on one of their arms.

In addition to Bình Hoà, there are three other sites across Vietnam where monuments of hate denouncing South Korean atrocities can be found. After Vietnam’s liberation in 1975, there was a movement to document the massacres by deployed soldiers, and in the 1980s, a small number of monuments were erected based on village records.

In total, more than 60 memorials were erected that listed only the names of victims. Only three monuments of hate with textual descriptions of the atrocities can be identified, as most of them were shoddily constructed during times of trouble and have since been destroyed.

The monuments of hate were erected to commemorate the victims and solicit an apology from the South Korean government, but the nature of those monuments was never fully revealed due to the diplomatic relations between the South Korean and Vietnamese governments.

An example of a monument that clouds the truth is, despite not being a monument of hate, the memorial stone dedicated to those killed in the village of Hà My, the inscription of which was covered by a mural of lotus flowers.

Located a 20-minute drive from Da Nang, a popular tourist destination for Koreans, the memorial in Hà My was built in 2001 with support from the Korean Vietnam Veterans’ Welfare Association.

The original inscription included a poem describing the tragedy. However, conflicts arose over the poem’s depiction of South Korean soldiers as mass murderers, and the inscription was eventually covered with a lotus mural.

The Vũng Tàu and Tho Lam monument of hate in the Đông Hòa district of Phú Yên Province, only has the words “monument of hate” left, and the rest of the inscription has been weathered away. The official name of the monument was changed to a memorial when the stone was restored.

In the meantime, the Bình Hoà monument of hate is estimated to have been re-erected at the entrance to the village in its current form in the early 1990s. Unlike other memorials, which are usually erected at the sites of atrocities, the Bình Hoà monument of hate is displayed at the entrance of the village to remind villagers of the tragedy.

The Bình Hoà stele of hate is the only monument that specifically shows the statistics of deaths and devastation, making it virtually the last surviving record of the South Korean military’s massacre of civilians.

There aren’t many survivors of Korea’s acts in Vietnam anymore. While South Korea has turned a blind eye to the atrocities, some villages, such as Bình Thanh, have continued to attempt to erect monuments of hate.

Survivors, traumatized by the atrocities, are still fighting for their lives. What they want now is a sincere apology.

“I no longer resent South Korea. All I want is an official apology showing that they are repenting and promising that something like this will never happen again,” said 65-year-old Nguyễn Thanh Tuấn, who, at the age of 8, was the only one in their family to survive.

By Koh Kyoung-tae, staff reporter; Kwak Jin-san, staff reporter; interpretation by Nguyễn Ngọc Tuyền, professor of Korean at the University of Đà Nẵng

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0517/8117159322045222.jpg) [Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later

[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner than later![[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0516/7417158465908824.jpg) [Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence- [Editorial] Yoon must stop abusing authority to shield himself from investigation

- [Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- [Column] How to win back readers who’ve turned to YouTube for news

- [Column] Welcome to the president’s pity party

- [Editorial] Korea must respond firmly to Japan’s attempt to usurp Line

- [Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- [Column] Will Seoul’s ties with Moscow really recover on their own?

- [Column] Samsung’s ‘lost decade’ and Lee Jae-yong’s mismatched chopsticks

Most viewed articles

- 1[Editorial] Transfers of prosecutors investigating Korea’s first lady send chilling message

- 2[Column] US troop withdrawal from Korea could be the Acheson Line all over

- 3[Column] When ‘fairness’ means hate and violence

- 4Xi, Putin ‘oppose acts of military intimidation’ against N. Korea by US in joint statement

- 5[Editorial] Intensifying US-China rivalry means Seoul must address uncertainty with Beijing sooner t

- 6[Exclusive] Unearthed memo suggests Gwangju Uprising missing may have been cremated

- 7‘Shot, stabbed, piled on a truck’: Mystery of missing dead at Gwangju Prison

- 8China calls US tariffs ‘madness,’ warns of full-on trade conflict

- 9China, Russia put foot down on US moves in Asia, ratchet up solidarity with N. Korea

- 10Putin’s trip to China comes amid 63% increase in bilateral trade under US-led sanctions