hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Exclusive] ‘More than $1,000 per child’: Park Chung-hee’s Korea ignored Belgium’s calls for action on adoption profiteering

As part of a major investigation into allegations about illegal activities by adoption agencies and collusion and negligence by the Korean government when many Korean children were being adopted overseas between the 1970s and the 1990s, Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has turned up documents from the 1970s detailing how the Belgian government complained to Seoul that adoption agencies were accepting payments for adoptions and asked for the issue to be addressed. The Korean government had claimed innocence about what it described as a private sector issue, these documents appear to show that Seoul was in fact aware of widespread illegal overseas adoption but did nothing to address that.

According to records of conversations that were prepared by Korea’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs between 1974 and 1981 and have now been acquired by the Hankyoreh, the Belgian government complained on several occasions about issues with the overseas adoption of Korean orphans, including the illegal involvement of brokers, but the Korean government apparently ignored that information. The issue was so important to the Belgian government that it requested a meeting with President Park Chung-hee himself.

Despite calls for action, none taken by Korean government

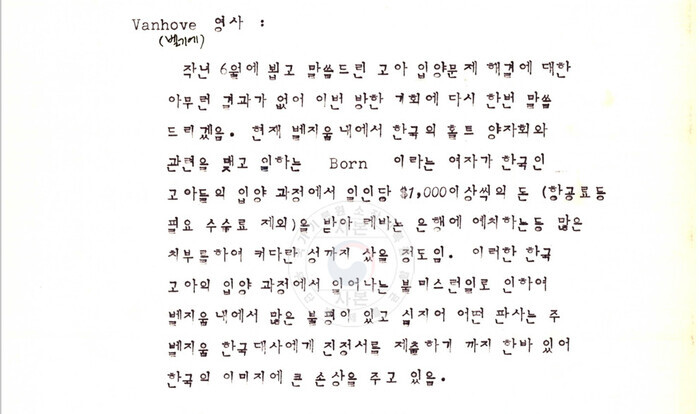

In a meeting on May 1, 1978, a Belgian consul to Korea by the name of Vanhove told the Korean Foreign Ministry’s European bureau chief that a Lebanese woman named Born working in partnership with Holt Adoption Program (Hold Children’s Services) was selling Korean orphans in Belgium for US$800-$1,200 per child. The consul added that the matter was of such urgency that he wanted an audience with the president to bring it to the attention of the Korean head of state.

Belgium was the destination country of the largest number of Korean orphans, after the US, Sweden, Denmark and Norway, until the late 1970s.

The Belgian government appears to have viewed this as a serious issue because facilitating adoptions for pay can be regarded as child trafficking.

Vanhove vocally complained during his meeting with the European bureau chief, remarking that he’d brought up the issue in a meeting with another bureau chief at the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs the previous year to no avail. He added that he’d advised Korean diplomats in Belgium that the Korean government needed to take measures to stop the involvement of brokers, but no measures had been taken.

Consul raised suspicions of Korean bureaucrats pocketing adoption commissions

It was illegal at the time, even under Korean law, to accept commissions for adoptions. The enforcement decree of the Act on Special Cases Concerning Adoption, which was enacted in 1977, permitted adoption agencies to collect the cost of arranging the adoption, either in part or in full, from the adoptive parents. In other words, the agency could only be compensated for its actual expenses.

During his meeting, Vanhove also brought up rumors circulating in Belgium that high-ranking officials in the Korean government were pocketing some of the adoption fees. There was speculation about a kind of cartel between private companies and the government.

The European bureau chief suggested that Vanhove speak to the official in charge of the matter: namely, the chief of the women and children’s affairs bureau at the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs. But Vanhove had already voiced similar complaints in a meeting with that official on June 27, 1977, a year earlier. He had paid a visit to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs because no meaningful steps had been taken over the past year, and now he was being shunted back to the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs.

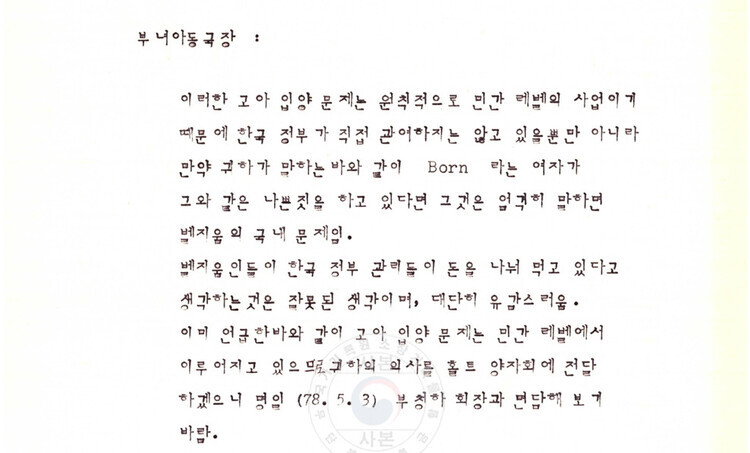

In a meeting with Vanhove the following day, the women and children’s affairs bureau chief described the adoption of orphans as a private-sector business issue in which the Korean government wasn’t involved and said that if there were brokers receiving commissions, that was an issue for Belgium to address.

The issue remained unresolved even as overseas adoption continued to expand. A report that the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs prepared for the Blue House in 1988 (which the Hankyoreh reported on last year) stated that the four adoption agencies were receiving an adoption commission of US$1,450 per child, the cost of airfare, and US$3,000-$4,000 for arranging the adoption on top of child-rearing expenses.

In recognition of the problem, the government convened a meeting with the heads of adoption agencies to address issues with the system. The agencies were criticized during the meeting for acquiring large amounts of real estate with company profits, squandering money on outrageous overhead, and collecting hefty commissions from adoptive parents.

“The Korean government appears to have used children as a diplomatic tool with the countries of Northern Europe, where there was high demand for adoption,” said Noh Helen, a professor of social welfare at Soongsil University who worked for Holt in the 1980s.

“It’s shocking that the Korean government would have shut its eyes to the poor practices in adoption at the time. That neglect caused considerable harm to the tens of thousands of adopted children, their birth families and their adoptive parents,” said Yung Fierens, 47, who was sent to Belgium for adoption in 1977.

“If the Korean government had taken the necessary measures, adopted children like me wouldn’t have been taken from our birth parents to a country all the way across the world.”

By Kwak Jin-san, staff reporter; Jang Ye-ji, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing? [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0705/2917201664129137.jpg) [Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?![[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0703/8717199957128458.jpg) [Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor- [Column] How opposing war became a far-right policy

- [Editorial] Korea needs to adjust diplomatic course in preparation for a Trump comeback

- [Editorial] Silence won’t save Yoon

- [Column] The miscalculations that started the Korean War mustn’t be repeated

- [Correspondent’s column] China-Europe relations tested once more by EV war

- [Correspondent’s column] Who really created the new ‘axis of evil’?

- [Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- [Column] Kim and Putin’s new world order

Most viewed articles

- 110 days of torture: Korean mental patient’s restraints only removed after death

- 2Months after outcry over “torture devices,” Justice Ministry proposes more restraints for immigratio

- 3Beleaguered economy could stymie Japan’s efforts to buoy the yen

- 4[Column] Is Korean democracy really regressing?

- 5Koreans are getting taller, but half of Korean men are now considered obese

- 6[Column] How tragedy pervades weak links in Korean labor

- 7Former bodyguard’s dark tale of marriage to Samsung royalty

- 8Real-life heroes of “A Taxi Driver” pass away without having reunited

- 9[Editorial] Exploiting foreign domestic workers won’t solve Korea’s birth rate problem

- 10Democrats ride wave of 1M signature petition for Yoon to be impeached