hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

[Interview] Participant in Gwangju Democratization Movement recalls experience of being labeled as “N. Korean soldier”

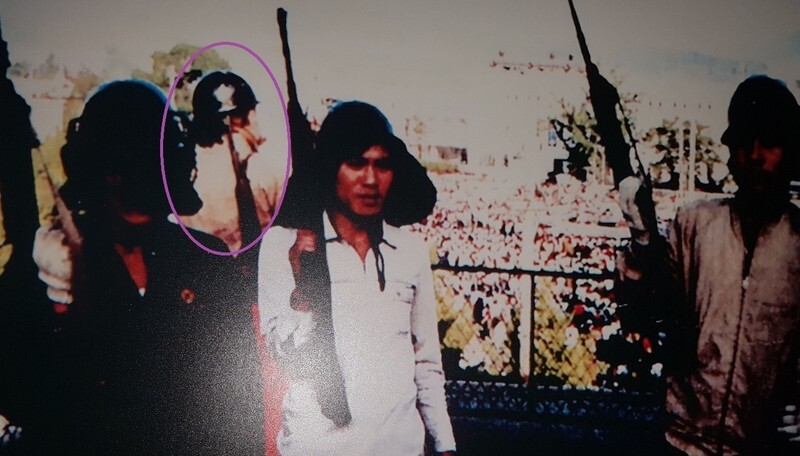

The mustachioed young man on the screen sings along to the national anthem, a helmet on his head. His eyes are pointed toward a demonstration on a plaza with a fountain in front of the old South Jeolla Provincial Office. Now 59, Gwak Hee-seong was a 19-year-old when he became a civilian militia member during the events of the Gwangju Democratization Movement of May 18, 1980, standing on the roof of the Gwangju YMCA with a gun in his hand.

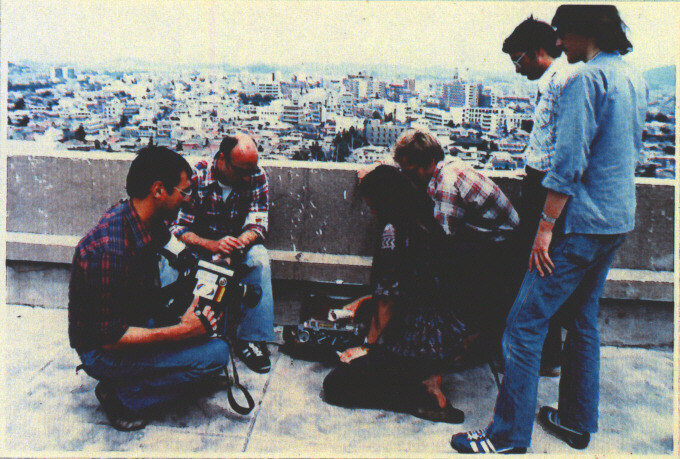

An image of Gwak in his younger days appears in video footage taken at the time by Jürgen Hinzpeter (1937-2016), a correspondent for a West German public broadcaster. Hinzpeter is the true protagonist of the film “A Taxi Driver.”

He first met Hinzpeter sometime around May 23, 1980. Accompanied by an interpreter, Hinzpeter went up to the YMCA rooftop and asked to be allowed to film the demonstration taking place in front of the provincial office. Gwak refused at first. “They [the leaders behind the uprising] told me not to agree to filming. They said it would be bad news if we survived,” he recalled.

Hinzpeter gave each of the citizen’s militia members a pack of Western cigarettes. When the cigarettes ran low, the young militia members started to become restless. That was when it happened -- somebody started up, and soon the citizens were singing the national anthem.

“Back then, I felt a lump in my throat just hearing the national anthem. And there were bodies piling up in the Sangmugwan [military gymnasium],” Gwak said. “But this foreign reporter who had been filming the demonstration suddenly turned the camera on me while I was singing the anthem. I had no idea I’d even been filmed.”

What led Gwak to become caught up in the turbulence of May 1980 was the noise of tanks. He’d applied to join the airborne special forces that January, but had been unable to enter due to family objections; since then, he’d been counting the days to his enlistment.

“I’d been messing around and hadn’t even realized [the Gwangju Uprising] had gotten started. We got together in a sash shop that a friend of mine had opened in Hwajeong [a neighborhood in Gwangju],” he explained.

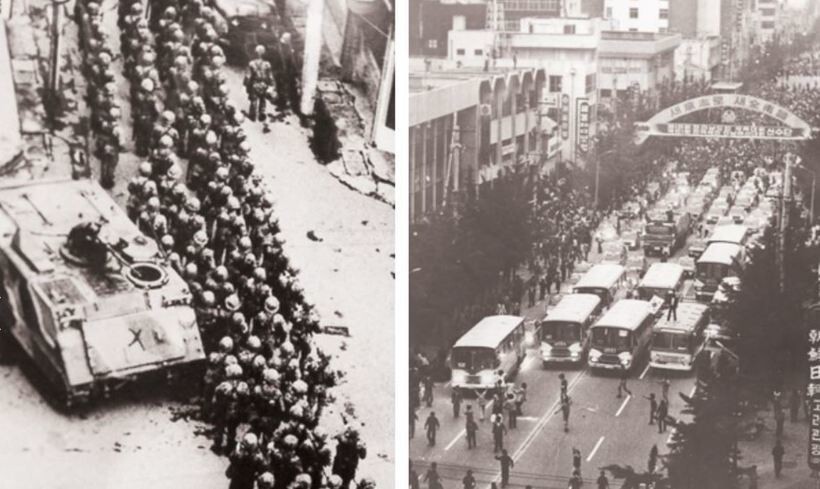

On the morning of May 19, he went out into the street with his friend Yang Dong-nam and saw lines of tanks. “I asked, ‘What’s going on?’ We kept walking up and saw tanks parked in front of the army general hospital,” he remembered. “There weren’t any cars on the street.” It was the day the military leader under Defense Security Commander Chun Doo-hwan began the full-scale deployment of tanks and troops to massacre the citizens of Gwangju.

Gwak took a bus heading to what was then the South Jeolla Provincial Office. Yang, who was with him at the time, remembers the date as May 20.

“They didn’t have an underground walkway in Nongseong [a neighborhood of Gwangju], but there was a sawmill nearby. In front of it, there were citizens driving a bus, and they told us, ‘Get on if you want to go to the provincial office.’ We got on, no questions asked. They parked at the Bank of Korea intersection downtown.”

Joined citizens’ militia after seeing bodies of innocent victims

Gwak saw the first dead body at the entrance to Chungjang Road.

“There was a body on a hand cart. It was covered with a Taegeukgi [South Korean flag], but you could see the face. What I felt after seeing that wasn’t fear, but something boiling up inside of me. I was angry, and I could hear myself cursing.”

The airborne troops fired tear gas and chased after the citizens. Taking flight, Gwak and Yang separated. Gwak ran to a store in the Sugi neighborhood and stuck his head underneath a wooden bench. The coarse grain underneath scratched his face, but he didn’t let out a sound. Soldiers ran inside and began asking the elderly proprietors about his location. Fortunately, they insisted that no one was there, and he was able to escape arrest. But as he emerged from the store, he ended up captured by the soldiers.

“I had long hair and such, and maybe they thought I was a junkman, because they gave me a few whacks with a club and then kind of winked at me to signal that I should get out of there.” It was a close call.

Gwak helped citizens’ militia arm itself

After the martial law forces opened fire on the public in front of the provincial office on May 21, citizens began carrying arms to protect themselves. Gwak suggested going to Hwasun, a county near Gwangju. He’d recalled the dynamite that he’d seen as an elementary school student when he brought lunch to his father who worked in the Hwasun coal mine. His father had lost his right hand, eyesight, and hearing in a 1968 explosion at the mine. As they made their way to Hwasun, Gwak picked up guns that had been abandoned by police at the Neoritjae checkpoint on the border between Gwangju and Hwasun. Turning back on his way to the coal mine, he picked up ammunition from a police branch and returned to Gwangju.

The city had been sealed off by the martial law forces, who had retreated to the outskirts. Gwak went to Asia Motors (now the Kia Motors factory in Gwangju) and came out with a military truck.

“Military trucks don’t use keys. They’ve got a lever you throw back. A lot of people came out with cars. They drove around in those. The people driving went to where they had a log barricade set up in Nongseong.” In the vehicle were around a dozen people, who stopped off along the way to ease their hunger with water and seaweed rolls. At that moment, there was a sudden sound of gunfire.

“A teenager in a high school drill uniform was coming up toward the truck. I yelled, ‘Don’t come up!’ But then he was hit with a bullet.”

With the uniformed boy in his passenger seat, Gwak drove to the Christian Hospital. It was his first time driving.

“My rear end was damp. The blood was running over my body and pooling underneath me. I covered it with a towel. He’d been shot underneath his eye, and there was a hole going back into his head.”

Gwak was half out of his wits. Coming out of the emergency room, the doctors shook their heads. “They wouldn’t let us into the hospital, so I just held that boy’s hand and patted his chest a couple times.”

He headed back toward the provincial office. The citizen countermeasures committee and martial law command had been negotiating, but had failed to reach an agreement. The martial law army demanded the return of the weapons, while the young people were demanding a fight to the death. The martial law army’s Operation Sangmu Chungjung -- the renewed suppression of Gwangju -- was scheduled for May 27.

Gwak was enlisted in the citizens’ army and put on patrol between the Jeonil Building and the Bank of Korea Intersection. That was when he learned what had happened to Yang Dong-nam, the friend he’d gotten separated from while they were making their escape. Yang was serving with the citizens’ army as well, on guard duty at the South Jeolla Provincial Office.

Shortly before the citizen’s army made its last stand, Gwak skipped out of Gwangju to stay alive. He’d been sent out to round up firearms when he saw a woman in a long skirt roaming the streets with a dazed expression, near the Wolsan Neighborhood Intersection. It was his mother. “Sometime later, I heard she’d been going from one morgue to another to find me, assuming I was dead,” Gwak recalled.

Escaped from provincial office on last day, forever burdened with guilt

Gwak couldn’t get any sleep that night, and he poured out his heart to his commanding officer in the citizens’ militia. The officer told him he was free to hand over his weapon and leave at any time. Skulking through the woods and side streets, Gwak managed to avoid the watchful eyes of the martial law troops and make it home within 36 hours. But he felt ashamed about having saved his own skin, and indebted to those who had died.

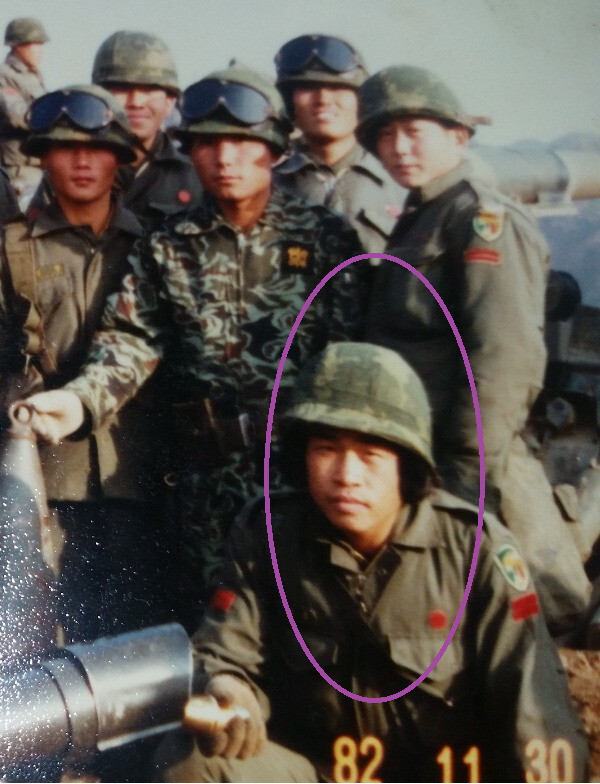

In Feb. 1982, Gwak enlisted in the army and completed his full term of service. Around that time, a friend who ran a video store privately showed him a video about the Gwangju Democratization Movement that people were passing around. Gwak learned, to his shock, that it was the video that had been shot by Jürgen Hinzpeter, the foreign correspondent, the same guy who’d given him the cigarettes. His friend had noticed that Gwak was shown singing the national anthem in the film; he urged Gwak to stay away from crowded areas, because he might be nabbed by the authorities.

After becoming a taxi driver in 1986, Gwak always kept his hair short and wore dress pants, a vest, and a necktie. He figured he’d have to present a clean-cut image to avoid being linked to the Gwangju movement. He didn’t even tell his wife that he’d been in the citizens’ militia until they had two sons.

While Gwak didn’t reminisce about the Gwangju Democratization Movement, he couldn’t hide the fact that he wouldn’t stand for injustice. In 1989, he joined other taxi drivers at his company on a strike aimed at breaking a union that toed the company line. After about 40 days, he was arrested on charges of committing violence under the Assembly and Demonstration Act.

Through a complicated series of events, Gwak was restored to his job and eventually became a union leader, a position he held for six years and four months. In 1992, he joined an association of taxi drivers who’d been involved in the Gwangju Democratization Movement and participated in volunteer activities, such as bathing residents at unaccredited welfare facilities.

The apartment that Gwak was renting was the site of a dramatic reunion with his old friend Yang Dong-nam, whom he hadn’t seen since the Gwangju movement. Yang related how he’d just got out of prison and talked about the suffering he’d faced for his role in the insurrection. Gwak found himself at a loss for words.

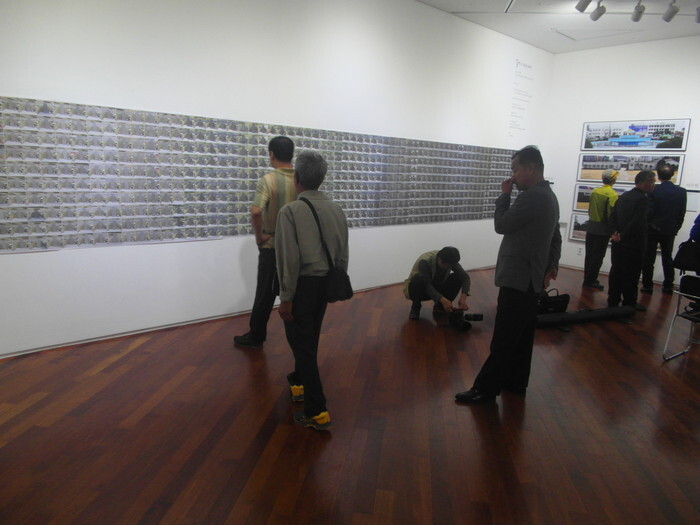

Four years ago, while making a living as a private taxi driver, Gwak took part in a photography therapy program at the Gwangju Trauma Center. Gwak was among seven “meritorious individuals” (people compensated by the government for their suffering in the Gwangju movement) who exhibited their works at Seoul Citizens’ Hall on May 16-23, 2016. He photographed each of the 741 graves at the May 18th National Cemetery and combined them into a single work of art.

This photography project was the first time he’d ever visited the cemetery. “I found myself wanting to find the grave of the teenager in the drill uniform. At each grave, I bowed twice, made a silent prayer, and took just one photograph. As I kept taking photographs, my feelings of guilt gradually faded,” he said.

Gwak’s campaign against misinformation surrounding Gwangju

Gwak has been an active participant in the campaign to debunk false narratives about the Gwangju Uprising. Ji Man-won, a reactionary pundit who has published misleading accounts of the uprising, identified Gwak as “Number 184” in a North Korean special forces unit supposedly dispatched to Gwangju. According to Ji, Gwak was actually Kwon Chun-hak, chair of the people’s committee in South Hwanghae Province.

In October 2015, Gwak and three other individuals sued Ji for defamation. Later, five other complaints (involving 15 people) and a lawsuit claiming defamation of the dead (namely, Kim Sa-bok, the real-life figure who inspired the main character in the film “A Taxi Driver”) were incorporated into a single trial, which is still ongoing. While Ji was sentenced to serve two years of prison and a fine of 1 million won (US$822) on Feb. 13, he hasn’t been taken into legal custody.

“When I got to the courthouse, I suddenly felt the urge to just throw myself at [Ji Man-won]. I wasn’t afraid of the judge or the prosecutors. I barely managed to hold myself back — it took a huge effort. [But I knew that] if I started a fight, it would just give the Gwangju movement a bad name. Still, it’s just mind-boggling for them to claim that my friend Yang Dong-nam was some big shot in North Korea. Do they think he’s some kind of Houdini? And how could I be a member of the North Korean special forces when I served in the South Korean army?”

Jung Dae-ha, Gwangju correspondent

Please direct comments or questions to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0502/1817146398095106.jpg) [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press![[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/child/2024/0501/17145495551605_1717145495195344.jpg) [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

[Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

- [Editorial] New weight of N. Korea’s nuclear threats makes dialogue all the more urgent

- [Guest essay] The real reason Korea’s new right wants to dub Rhee a founding father

- [Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- [Editorial] Japan’s rewriting of history with Korea has gone too far

Most viewed articles

- 11 in 3 S. Korean security experts support nuclear armament, CSIS finds

- 2Months and months of overdue wages are pushing migrant workers in Korea into debt

- 3Bills for Itaewon crush inquiry, special counsel probe into Marine’s death pass National Assembly

- 4[Reporter’s notebook] In Min’s world, she’s the artist — and NewJeans is her art

- 5[Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- 6S. Korean Defense Ministry rejects petition from Vietnam War civilian massacre survivors

- 7[Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- 8[Reportage] A petition of tears by victims of civilian massacres during Vietnam War

- 9Civic groups demand S. Korean government take responsibility for Vietnam War civilian massacres

- 10Another court rules NIS to release data on Vietnam War civilian massacres