hankyoreh

Links to other country sites 다른 나라 사이트 링크

30 years of the N. Korean nuclear threat: How distrust precluded peace

On March 12, 1993, North Korea declared on Korean Central Television its withdrawal from the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT) as a “measure to protect the state’s supreme interests.” This was the beginning of the nuclear problem on the Korean Peninsula, which was to continue for the next 30 years. Ever since, the Korean Peninsula has been trapped in a vicious cycle of negotiations, followed by the scrapping of agreements, mutual recrimination, and the escalation of tensions.

In 1992, a year before North Korea’s withdrawal from the NPT, the two Koreas signed the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, but when the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) announced in January of 1993 that North Korea was extracting large amounts of plutonium, the mood changed rapidly. South Korea and the US announced the resumption of the annual Team Spirit exercises, which had been suspended since 1993.

North Korea deemed South Korea and the US’ Team Spirit exercises and the IAEA’s demand for a special inspection of North Korea’s nuclear facilities clear existential threats.

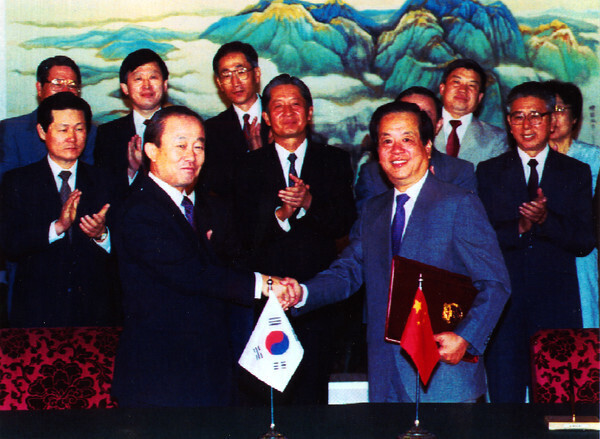

North Korea’s nuclear weapons program started when the country was deserted by its “allies,” China and Russia, with the disintegration of the Cold War system. Particularly, when South Korea, through its “Nordpolitik” managed to establish diplomatic relations with Russia in 1990 and then with China on Aug. 24, 1992, North Korea was shocked.

On July 15, 1992, a month before diplomatic ties were established between South Korea and China, China sent a delegation headed by then-Chinese Foreign Minister Qian Qichen to Pyongyang to explain the situation. After meeting with Qian and his companions at his residence in Mount Myohyang, North Korean leader Kim Il-sung determined that China had committed an act of betrayal, declaring North Korea would “walk the autonomous route.” Afterward, the country hastened its nuclear development efforts.

In 1994, the Korean Peninsula hurtled dangerously close to war, tensions having been escalated by North Korea’s nuclear weapons program. On March 19 of that year, during the eighth inter-Korean working-level meeting held for the exchange of special envoys between the two Koreas, the top delegate of the North side, Park Yong-su, told Song Yong-dae, the top delegate of the South, that Seoul would be turned into a “sea of flames” should war break out. At the time, the US went so far as to consider precision striking North Korea.

Things were about to reach a breaking point on the Korean Peninsula when former US President Jimmy Carter visited North Korea on June 15 that year, averting a crisis. Meeting Kim Il-sung in Pyongyang, Carter promised that the US and others would assist North Korea in building a light-water reactor if the North stopped developing nuclear weapons. Later on, North Korea and the US signed a basic agreement. The two countries agreed that North Korea would stop operating its nuclear facilities in Yongbyon, agree to inspections, remain in the NPT and carry out the Joint Declaration on the Denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula, and not reprocess used nuclear fuel.

The second nuclear crisis on the Korean Peninsula began in 2002.

The crisis occurred when, during their visit to Pyongyang, US negotiators headed by special envoy James Kelly mentioned the fact that North Korea was secretly developing nuclear warheads using high-enriched uranium on Oct. 3, 2002. On Aug. 27, 2003, six countries including the two Koreas, the US, China, Japan, and Russia commenced six-party talks in order to solve the North Korean nuclear problem.

These six-party talks led to an agreement on Sept. 19, 2005. Through this agreement, North Korea promised to abandon all its nuclear weapons and nuclear initiatives and rejoin the NPT as soon as possible. In return, the US promised to normalize its relations with North Korea. At the same time, the nations participating in the six-party talks agreed to respect North Korea’s right to use nuclear power peacefully and hold discussions related to providing North Korea with light-water reactors.

But only a day later, on Sept. 20, the US froze US$24 million deposited in roughly 50 North Korea-related accounts at Banco Delta Asia, citing concerns of illegal money laundering by North Korea. North Korea fiercely opposed this move, which culminated in the first nuclear test in the rural village of Punggye, Kilju County, North Hamgyong Province, on Oct. 9, 2006.

North Korea and the US resumed negotiations within the six-party talks framework following the nuclear test. Then, an agreement was reached on Oct. 3 which outlined that North Korea would receive economic and energy support in return for disabling its nuclear facilities.

On June 27, 2008, North Korea issued a live broadcast of its demolition of the Yongbyon nuclear reactor’s cooling tower. The US government removed it from its list of “state sponsors of terrorism.” The North also granted access to its nuclear facilities to a team of IAEA inspectors, and the disabling of its nuclear facilities resumed.

But conflict erupted again between Pyongyang and Washington over the verification methods. On May 25, 2009, the North carried out a second nuclear test.

After current leader Kim Jong-un came to power, North Korea officially declared itself a nuclear state.

It revised the preamble of its Constitution in 2012 to state that Kim had “developed the DPRK into an invincible politico-ideological power, a nuclear state and an unchallengeable military power, and opened a broad avenue for the building of a powerful socialist country.”

As the nuclear issue intensified in 2017, it plunged the Korean Peninsula into a crisis on par with the events of 1994.

That same year, the doorway to negotiations opened again. Moon Jae-in came to office as South Korean president and used the 2018 Winter Olympics in Pyeongchang as an opportunity to bring Pyongyang to the table for dialogue on the international stage.

The two sides’ summit in Pyongyang led to the military agreement of Sept. 19, 2018, in which they agreed to take practical steps to make the Korean Peninsula into a region of permanent peace. They made plans for a test withdrawal of guard posts in the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and disarmament of the Joint Security Area.

On June 12 of that year, North Korea and the US had a summit in Singapore, where the leaders agreed on four areas — implementing complete denuclearization, guaranteeing a peace regime, pursuing normalization of bilateral relations, and repatriating the remains of soldiers killed during the Korean War — and pledged to hold a follow-up summit.

The following year, the mood shifted drastically.

In February, a second North Korea-US summit in Hanoi broke down. In his memoir “The Room Where It Happened,” former White House national security advisor John Bolton — an ultra-hard-liner and hawk on North Korea — explained that Kim had spoken to then-US President Donald Trump in their meeting at the Metropole Hotel about what a major concession the North had made with the Yongbyon nuclear facility, and how much attention it would receive in the US press.

But Trump asked Kim whether he could present any suggestions besides Yongbyon, and whether he could ask for a 1% reduction of sanctions rather than their full removal. Out of nowhere, he was making additional demands that Pyongyang would never be willing to accept.

“This was beyond doubt the worst moment of the meeting,” Bolton wrote. “If Kim Jong-un had said yes there, they might have had a deal, disastrously for America. Fortunately, he wasn’t biting, saying he was getting nothing, omitting any mention of the sanctions being lifted.”

After the dramatic progress that Pyongyang had made with Seoul and Washington, a deep valley of distrust once again yawned.

Commenting on the Hanoi breakdown in a telephone interview with the Hankyoreh, former South Korean Minister of Unification Kim Yeon-chul said, “In the US’ case, there was scarcely any policy coordination between working-level officials and the president.”

“South Korea’s role was fairly limited,” he explained, adding that he thought “there should be an assessment of whether [Seoul] properly played the part of an honest mediator.”

In the summer of 2023, the Korean Peninsula once again finds itself in a deep chill. President Yoon Suk-yeol in the South has come out with an “audacious initiative” promising economic and livelihood support to the North if it ceases its nuclear weapon development and pursues practical denuclearization. But in practice, his administration’s actions have been skewed toward ultra-hard-line policies on Pyongyang.

This approach has drawn bitter denunciations from the North. In a statement on Aug. 19, 2022, Workers’ Party of Korea Central Committee vice department director Kim Yo-jong asserted that Pyongyang would “not sit face to face with” Yoon.

“Before China and the Soviet Union developed nuclear weapons, North Korea’s position was anti-nuke,” explained Koo Kab-woo, a professor at the University of North Korean Studies.

“Now that inter-Korean relations have spiraled into a worst-case scenario, it’s time for us to work together to think of what measures we can adopt to take North Korea back to its ‘no nukes’ era,” he urged.

By Shin Hyeong-cheol, staff reporter

Please direct questions or comments to [english@hani.co.kr]

Editorial・opinion

![[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0509/221715238827911.jpg) [Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea![[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war](https://flexible.img.hani.co.kr/flexible/normal/500/300/imgdb/original/2024/0507/7217150679227807.jpg) [Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war

[Guest essay] Preventing Korean Peninsula from becoming front line of new cold war- [Column] The state is back — but is it in business?

- [Column] Life on our Trisolaris

- [Editorial] Penalties for airing allegations against Korea’s first lady endanger free press

- [Editorial] Yoon must halt procurement of SM-3 interceptor missiles

- [Guest essay] Maybe Korea’s rapid population decline is an opportunity, not a crisis

- [Column] Can Yoon steer diplomacy with Russia, China back on track?

- [Column] Season 2 of special prosecutor probe may be coming to Korea soon

- [Column] Park Geun-hye déjà vu in Yoon Suk-yeol

Most viewed articles

- 1Korea likely to shave off 1 trillion won from Indonesia’s KF-21 contribution price tag

- 2Nuclear South Korea? The hidden implication of hints at US troop withdrawal

- 3[Editorial] Perilous stakes of Trump’s rhetoric around US troop pullout from Korea

- 4With Naver’s inside director at Line gone, buyout negotiations appear to be well underway

- 5In Yoon’s Korea, a government ‘of, by and for prosecutors,’ says civic group

- 6[Column] ‘Choson’: Is it time we start referring to N. Korea in its own terms?

- 7‘Free Palestine!’: Anti-war protest wave comes to Korean campuses

- 8How many more children like Hind Rajab must die by Israel’s hand?

- 9Overseeing ‘super-large’ rocket drill, Kim Jong-un calls for bolstered war deterrence

- 10[Photo] ‘End the genocide in Gaza’: Students in Korea join global anti-war protest wave